Haussmann's renovation of Paris

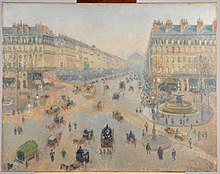

It included the demolition of medieval neighbourhoods that were deemed overcrowded and unhealthy by officials at the time, the building of wide avenues, new parks and squares, the annexation of the suburbs surrounding Paris, and the construction of new sewers, fountains and aqueducts.

In 1845, the French social reformer Victor Considerant wrote: "Paris is an immense workshop of putrefaction, where misery, pestilence and sickness work in concert, where sunlight and air rarely penetrate.

[2] In 1840, a doctor described one building in the Île de la Cité where a single 5-square-metre room (54 sq ft) on the fourth floor was occupied by twenty-three people, both adults and children.

[5] The urban problems of Paris had been recognized in the 18th century; Voltaire complained about the markets "established in narrow streets, showing off their filthiness, spreading infection and causing continuing disorders."

"[6][page needed] The 18th century architectural theorist and historian Quatremere de Quincy had proposed establishing or widening public squares in each of the neighbourhoods, expanding and developing the squares in front the Cathedral of Nôtre Dame and the church of Saint Gervais, and building a wide street to connect the Louvre with the Hôtel de Ville, the new city hall.

Pierre-Louis Moreau-Desproux, the architect in chief of Paris, suggested paving and developing the embankments of the Seine, building monumental squares, clearing the space around landmarks, and cutting new streets.

"If only the heavens had given me twenty more years of rule and a little leisure," he wrote while in exile on Saint Helena, "one would vainly search today for the old Paris; nothing would remain of it but vestiges.

In 1833, the new prefect of the Seine under Louis-Philippe, Claude-Philibert Barthelot, comte de Rambuteau, made modest improvements to the sanitation and circulation of the city.

[10] He constructed 180 kilometres of sidewalks, a new street, rue Lobau; a new bridge over the Seine, the Pont Louis-Philippe; and cleared an open space around the Hôtel de Ville.

To access the central market at Les Halles, he built a wide new street (today's rue Rambuteau) and began work on the Boulevard Malesherbes.

The Péreire brothers organised a new company which raised 24 million francs to finance the construction of the street, in exchange for the rights to develop real estate along the route.

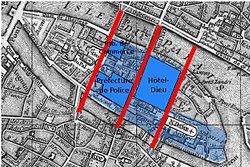

"[22] The Boulevard Sébastopol ended at the new Place du Châtelet; a new bridge, the Pont-au-Change, was constructed across the Seine, and crossed the island on a newly built street.

The official parliamentary report of 1859 found that it had "brought air, light and healthiness and procured easier circulation in a labyrinth that was constantly blocked and impenetrable, where streets were winding, narrow, and dark.

[30] Haussmann found creative ways to raise more money for the grand projects while circumventing the Legislative Assembly, whose approval was otherwise needed for direct borrowing increases.

[34] Numerous factories and workshops had been established in the suburbs, some to specifically avoid paying the Octroi, a tax on goods and materials paid at entry points into Paris.

[40] The debates in the Legislative Assembly surrounding the authorization of these new agreements lasted 11 sessions, with critics attacking Haussmann's borrowing, his questionable funding mechanisms, and the City of Paris's governing structure.

[43] At the same time Napoleon III was increasingly ill, suffering from gallstones which were to cause his death in 1873, and preoccupied by the political crisis that would lead to the Franco-Prussian War.

Napoleon III had already begun construction of the Bois de Boulogne, and wanted to build more new parks and gardens for the recreation and relaxation of the Parisians, particularly those in the new neighborhoods of the expanding city.

Haussmann wrote in his memoirs that Napoleon III instructed him: "do not miss an opportunity to build, in all the arrondissements of Paris, the greatest possible number of squares, in order to offer the Parisians, as they have done in London, places for relaxation and recreation for all the families and all the children, rich and poor.

"[48] In response Haussmann created twenty-four new squares; seventeen in the older part of the city, eleven in the new arrondissements, adding 15 hectares (37 acres) of green space.

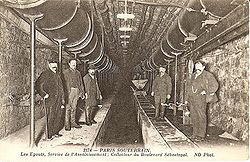

[55] While he was rebuilding the boulevards of Paris, Haussmann simultaneously rebuilt the dense labyrinth of pipes, sewers and tunnels under the streets which provided Parisians with basic services.

Haussmann wrote in his mémoires: "The underground galleries are an organ of the great city, functioning like an organ of the human body, without seeing the light of day; clean and fresh water, light and heat circulate like the various fluids whose movement and maintenance serves the life of the body; the secretions are taken away mysteriously and don't disturb the good functioning of the city and without spoiling its beautiful exterior.

Haussmann forced them to consolidate into a single company, the Compagnie parisienne d'éclairage et de chauffage par le gaz, with rights to provide gas to Parisians for fifty years.

He also criticized Haussmann for reducing the Jardin du Luxembourg from thirty to twenty-six hectares in order to build the rues Medici, Guynemer and Auguste-Comte; for giving away a half of Parc Monceau to the Pereire brothers for building lots, in order to reduce costs; and for destroying several historic residences along the route of the Boulevard Saint-Germain, because of his unwavering determination to have straight streets.

[68] Emile Zola repeated that argument in his early novel, La Curée; "Paris sliced by strokes of a saber: the veins opened, nourishing one hundred thousand earth movers and stone masons; criss-crossed by admirable strategic routes, placing forts in the heart of the old neighborhoods.

[70] The argument that the boulevards were designed for troop movements was repeated by 20th century critics, including the French historian, René Hérron de Villefosse, who wrote, "the larger part of the piercing of avenues had for its reason the desire to avoid popular insurrections and barricades.

"[72] The Paris urban historian Patrice de Moncan wrote: "To see the works created by Haussmann and Napoleon III only from the perspective of their strategic value is very reductive.

His desire to make Paris, the economic capital of France, a more open, more healthy city, not only for the upper classes but also for the workers, cannot be denied, and should be recognised as the primary motivation.

He was also blamed for reducing the amount of housing available for low income families, forcing low-income Parisians to move from the center to the outer neighborhoods of the city, where rents were lower.

His defenders also noted that Napoleon III and Haussmann made a special point to build an equal number of new boulevards, new sewers, water supplies, hospitals, schools, squares, parks and gardens in the working class eastern arrondissements as they did in the western neighborhoods.