Hayashi track

After a protostar ends its phase of rapid contraction and becomes a T Tauri star, it is extremely luminous.

While slowly contracting, the star follows the Hayashi track downwards, becoming several times less luminous but staying at roughly the same surface temperature, until either a radiative zone develops, at which point the star starts following the Henyey track, or nuclear fusion begins, marking its entry onto the main sequence.

The shape and position of the Hayashi track on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram depends on the star's mass and chemical composition.

Stars between 0.5 and 3 M☉ develop a radiative zone prior to reaching the main sequence.

In 1961, Professor Chushiro Hayashi published two papers[2][3] that led to the concept of the pre-main-sequence and form the basis of the modern understanding of early stellar evolution.

Hayashi realized that the existing model, in which stars are assumed to be in radiative equilibrium with no substantial convection zone, cannot explain the shape of the red-giant branch.

[4] He therefore replaced the model by including the effects of thick convection zones on a star's interior.

A few years prior, Osterbrock proposed deep convection zones with efficient convection, analyzing them using the opacity of H− ions (the dominant opacity source in cool atmospheres) in temperatures below 5000 K. However, the earliest numerical models of Sun-like stars did not follow up on this work and continued to assume radiative equilibrium.

Modelling stars as polytropes with index 3/2 (in other words, assuming they follow a pressure-density relationship of

These stars rapidly contract due to gravity before settling to a quasistatic, fully convective state on the Hayashi tracks.

The forbidden zone is the region on the HR diagram to the right of the Hayashi track where no star can be in hydrostatic equilibrium, even those that are partially or fully radiative.

Newborn protostars start out in this zone, but are not in hydrostatic equilibrium and will rapidly move towards the Hayashi track.

Imagine a parcel of gas that starts at radial position r, but moves upwards to r + dr in a sufficiently short time that it exchanges negligible heat with its surroundings—in other words, the process is adiabatic.

This means that if a parcel of gas rises a tiny bit, it will be more dense than its surroundings and sink back to where it came from.

Stars form when small regions of a giant molecular cloud collapse under their own gravity, becoming protostars.

This is a good approximation for very young pre-main-sequence stars because they are still cool and highly opaque, so that radiative transport is insufficient to carry away the generated energy and convection must occur.

Stars heavier than 0.5 M☉ have higher interior temperatures, which decreases their central opacity and allows radiation to carry away large amounts of energy.

The star is then no longer on the Hayashi track, and experiences a period of rapidly increasing temperature at nearly constant luminosity.

This is called the Henyey track, and ends when temperatures are high enough to ignite hydrogen fusion in the core.

The convective interior is assumed to be an ideal monatomic gas with a perfectly adiabatic temperature gradient:

In cool stellar atmospheres (T < 5000 K), like those of newborn stars, the dominant source of opacity is the H− ion, for which

The fact that B is positive indicates that the Hayashi track shifts left on the HR diagram, towards higher temperatures, as mass increases.

Although this model is extremely crude, these qualitative observations are fully supported by numerical simulations.

In Stellar Interiors,[6] Hansen, Kawaler, and Trimble go through a similar derivation without neglecting multiplicative constants and arrived at

The authors note that the coefficient of 2600 K is too low—it should be around 4000 K—but this equation nevertheless shows that temperature is nearly independent of luminosity.

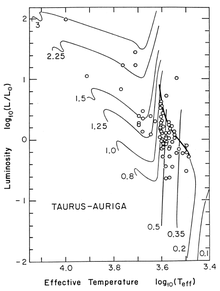

The diagram at the top of this article shows numerically computed stellar evolution tracks for various masses.

An isochrone is created by taking stars of every conceivable mass, evolving them forwards to the same age, and plotting all of them on the color–magnitude diagram.

[1] The lower diagram shows Hayashi tracks for various masses, along with T Tauri observations collected from a variety of sources.

In effect, stars are "born" onto the birthline before evolving downwards along their respective Hayashi tracks.

The birthline exists because stars formed from overdense cores of giant molecular clouds in an inside-out manner.

Low-mass stars have nearly vertical evolution tracks until they arrive on the main sequence. For more-massive stars, the Hayashi track bends to the left into the Henyey track . Even more-massive stars are born directly onto the Henyey track.

The end (leftmost point) of every track is labeled with the star's mass in solar masses ( M ☉ ), and represents its position on the main sequence. The red curves labeled in years are isochrones at the given ages. In other words, stars 10 5 years old lie along the curve labeled 10 5 , and similarly for the other 3 isochrones.