Healthcare in Sweden

The health care system in Sweden is financed primarily through taxes levied by county councils and municipalities.

[3] Sweden's health care system is organized and managed on three levels: national, regional and local.

The ministry, along with other government bodies, supervises activities at the lower levels, allocates grants, and periodically evaluates services to ensure correspondence to national goals.

At the local level, municipalities are responsible for maintaining the immediate environment of citizens, such as water supply and social welfare services.

A national Health Information Exchange platform provides a single point of connectivity to the many different systems.

In April 2015 Västernorrland County ordered its officials to find ways to limit the profits private companies can reap from running publicly funded health services.

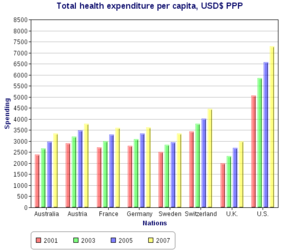

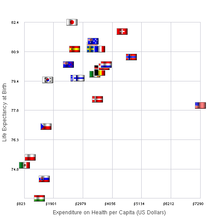

[6] Costs for health and medical care amounted to approximately 9 percent of Sweden's gross domestic product in 2005, a figure that remained fairly stable since the early 1980s.

[7] Seventy-one percent of health care is funded through local taxation, and county councils have the right to collect income tax.

The state finances the bulk of health care costs, with the patient paying a small nominal fee for examination.

In a sample of 13 developed countries Sweden was eleventh in its population weighted usage of medication in 14 classes in 2009 and twelfth in 2013.

The drugs studied were selected on the basis that the conditions treated had high incidence, prevalence and/or mortality, caused significant long-term morbidity and incurred high levels of expenditure and significant developments in prevention or treatment had been made in the last 10 years.

[14] According to the Euro health consumer index the Swedish score for technically excellent healthcare services, which they rated 10th in Europe in 2015, is dragged down by access and waiting time problems, in spite of national efforts such as Vårdgaranti.

This is an increase of over half a million fully covered by private health insurance compared to 2000.

This report concluded that the current system could not adequately guarantee patient safety in any of the hospitals inspected.

Peder Carlsson, the unit chief at IVO who led the inspection said: “Patients do not get an acceptable amount of food, fluids or basic treatment, and according to our information, patients can be required to lie for several hours in their own faeces and urine.” Swedish news agency TT quoted Carlsson as saying: “This is a terrible situation, totally unacceptable and it is particularly striking that this is happening in the hospitals we have in our country".