Heat engine

A heat engine is a system that transfers thermal energy to do mechanical or electrical work.

A heat source generates thermal energy that brings the working substance to the higher temperature state.

The working substance can be any system with a non-zero heat capacity, but it usually is a gas or liquid.

In general, an engine is any machine that converts energy to mechanical work.

[5] Although this efficiency limitation can be a drawback, an advantage of heat engines is that most forms of energy can be easily converted to heat by processes like exothermic reactions (such as combustion), nuclear fission, absorption of light or energetic particles, friction, dissipation and resistance.

Typically, the term "engine" is used for a physical device and "cycle" for the models.

The theoretical model can be refined and augmented with actual data from an operating engine, using tools such as an indicator diagram.

In any case, fully understanding an engine and its efficiency requires a good understanding of the (possibly simplified or idealised) theoretical model, the practical nuances of an actual mechanical engine and the discrepancies between the two.

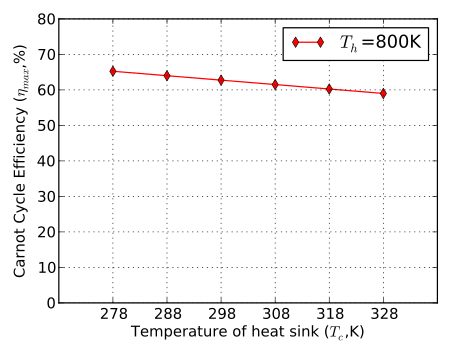

On Earth, the cold side of any heat engine is limited to being close to the ambient temperature of the environment, or not much lower than 300 kelvin, so most efforts to improve the thermodynamic efficiencies of various heat engines focus on increasing the temperature of the source, within material limits.

Significant energy may be consumed by auxiliary equipment, such as pumps, which effectively reduces efficiency.

In addition, externally heated engines can often be implemented in open or closed cycles.

Power stations are examples of heat engines run in a forward direction in which heat flows from a hot reservoir and flows into a cool reservoir to produce work as the desired product.

In general heat engines exploit the thermal properties associated with the expansion and compression of gases according to the gas laws or the properties associated with phase changes between gas and liquid states.

It involves the rising of warm and moist air in the earth's equatorial region and the descent of colder air in the subtropics creating a thermally driven direct circulation, with consequent net production of kinetic energy.

[11] In phase change cycles and engines, the working fluids are gases and liquids.

Internal combustion engine versions of these cycles are, by their nature, not reversible.

Refrigeration cycles include: The Barton evaporation engine is a heat engine based on a cycle producing power and cooled moist air from the evaporation of water into hot dry air.

In such mesoscopic heat engines, work per cycle of operation fluctuates due to thermal noise.

In general, the efficiency of a given heat transfer process is defined by the ratio of "what is taken out" to "what is put in".

In the case of an engine, one desires to extract work and has to put in heat

The theoretical maximum efficiency of any heat engine depends only on the temperatures it operates between.

is positive because isothermal expansion in the power stroke increases the multiplicity of the working fluid while

Mathematical analysis can be used to show that this assumed combination would result in a net decrease in entropy.

By its nature, any maximally efficient Carnot cycle must operate at an infinitesimal temperature gradient; this is because any transfer of heat between two bodies of differing temperatures is irreversible, therefore the Carnot efficiency expression applies only to the infinitesimal limit.

are allowed to be different from the temperatures of the substance going through the reversible Carnot cycle:

The heat transfers between the reservoirs and the substance are considered as conductive (and irreversible) in the form

and the classical Carnot result is found but at the price of a vanishing power output.

If instead one chooses to operate the engine at its maximum output power, the efficiency becomes This model does a better job of predicting how well real-world heat-engines can do (Callen 1985, see also endoreversible thermodynamics): As shown, the Curzon–Ahlborn efficiency much more closely models that observed.

Heat engines have been known since antiquity but were only made into useful devices at the time of the industrial revolution in the 18th century.

Engineers have studied the various heat-engine cycles to improve the amount of usable work they could extract from a given power source.