Hebrew cantillation

The chants are written and notated in accordance with the special signs or marks printed in the Masoretic Text of the Bible, to complement the letters and vowel points.

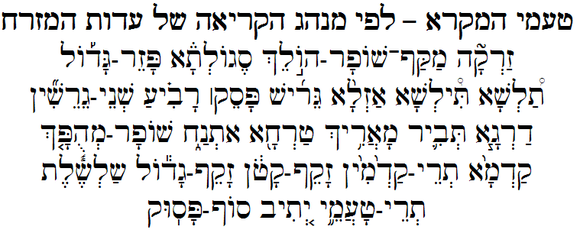

These marks are known in English as 'accents' (diacritics), 'notes' or trope symbols, and in Hebrew as taʿamei ha-mikra (טעמי המקרא) or just teʿamim (טעמים).

The musical motifs associated with the signs are known in Hebrew as niggun or neginot (not to be confused with Hasidic nigun) and in Yiddish as trop (טראָפ): the word trope is sometimes used in Jewish English with the same meaning.

Up to eight different letters are found, depending on the importance of the break and where it occurs in the verse: these correspond roughly to the disjunctives of the Tiberian system.

This system is reflected in the cantillation practices of the Yemenite Jews, who now use the Tiberian symbols, but tend to have musical motifs only for the disjunctives and render the conjunctives in a monotone.

Early manuscripts, by contrast, are mainly concerned with showing phrases: for example the tifcha-etnachta, zarqa-segolta and pashta-zaqef sequences, with or without intervening unaccented words.

The manuscripts are extremely fragmentary, no two of them following quite the same conventions, and these marks may represent the individual reader's aide-memoire rather than a formal system of punctuation (for example, vowel signs are often used only where the word would otherwise be ambiguous).

In particular, it was necessary to invent a range of different conjunctive accents to show how to introduce and elaborate the main motif in longer phrases.

As the accents were (and are) not shown on a Torah scroll, it was found necessary to have a person making hand signals to the reader to show the tune, as in the Byzantine system of neumes.

It is speculated that both the shapes and the names of some of the accents (e.g. tifcha, literally "hand-breadth") may refer to the hand signals rather than to the syntactical functions or melodies denoted by them.

Each community re-interpreted its reading tradition so as to allocate one short musical motif to each symbol: this process has gone furthest in the Western Ashkenazi and Ottoman (Jerusalem-Sephardi, Syrian etc.)

Learning the accents and their musical rendition is now an important part of the preparations for a bar mitzvah, as this is the first occasion on which a person reads from the Torah in public.

In the early period of the Reform movement there was a move to abandon the system of cantillation and give Scriptural readings in normal speech (in Hebrew or in the vernacular).

Depending on which disjunctive follows, this may be replaced by mercha, mahpach, darga, qadma, telisha qetannah or yerach ben yomo.

Where two words are written in the construct state (for example, pene ha-mayim, "the face of the waters"), the first noun (nomen regens) invariably carries a conjunctive.

For example, the words qol qore bamidbar panu derekh YHWH (Isaiah 40:3) is translated in the Authorised Version as "The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the LORD".

(In Yiddish the word is leynen 'read', derived from Latin legere, giving rise to the Jewish English verb "to leyn".)

The musical value of the cantillation signs serves the same function for Jews worldwide, but the specific tunes vary between different communities.

[9] A similar reconstructive proposal was developed by American composer and pianist Jeffrey Burns [de] and posthumously published in 2011.

[10] In the Ashkenazic musical tradition for Te'raim, each of the local geographical customs includes a total of six major and numerous minor separate melodies for Tera'im: The Ashkenazic tradition preserves no melody for the special cantillation notes of Psalms, Proverbs, and Job, which were not publicly read in the synagogue by European Jews.

However, the Ashkenazic yeshiva known as Aderet Eliyahu, or (more informally) Zilberman's, in the Old City of Jerusalem, uses an adaptation of the Syrian cantillation-melody for these books, and this is becoming more popular among other Ashkenazim as well.

[citation needed] At the beginning of the twentieth century there was a single Ottoman-Sephardic tradition (no doubt with local variations) covering Turkey, Syria, Israel and Egypt.

The Jews of North Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and Yemen all had local musical traditions for cantillation.

Spanish and Portuguese Jews have a special tune for the Ten Commandments when read according to the ta'am elyon, known as "High Na'um", which is also used for some other words and passages which it is desired to emphasize.

[13] Other communities, such as the Syrian Jews, observe the differences between the two sets of cantillation marks for the Ten Commandments but have no special melody for ta'am 'elyon.

For example, the Yemenite community teaches a simplified melody for children, to be used both in school and when they are called to read the sixth aliyah.

For learning purposes, the t'amim are arranged in a traditional order of recitation called a "zarqa table", showing both the names and the symbols themselves.

Otherwise, there is often a customary intonation used in the study of Mishnah or Talmud, somewhat similar to an Arabic mawwal, but this is not reduced to a precise system like that for the Biblical books.

[33] The Jewish-born Christian convert Ezekiel Margoliouth translated the New Testament to Hebrew in 1865 with cantillation marks added.

[34] Khazdan E. (2021) From Masoretic Signs to Cantillation Marks: Initial Steps (On the Virtual Dialogue between Alfonso de Zamora and Johannes Reuchlin).

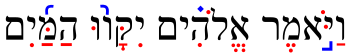

Letters in black, niqqud ( vowel points ) and d'geshim ( gemination marks) in red, cantillation in blue.

Bare transliteration: wy‘mr ‘lhym yqww hmym.

With accents: way-yōmer ĕlōhīm yiqqāwū ham-mayim.