Hegemony

[12] The hegemons were appointed by feudal lord conferences and were nominally obliged to support the King of Zhou,[13] whose status parallel to that of the Roman Pope in the medieval Europe.

From the reign of Duke Xian on, "Qin gradually swallowed up the six [other] states until, after hundred years or so, the First Emperor was able to bring all kings under his power.

The remaining five great warring states of China joined in the anti-hegemonic coalition and attacked Qin in 318 BC.

Officially, Rome's client states were outside the whole Roman imperium, and preserved their entire sovereignty and international rights and privileges.

[24] Those who are conventionally called by modern historians of Rome "client kings" were referred to as "allies and friends" of the Roman people.

[35] The Roman hegemony of the late Republic left to the Mediterranean kings internal autonomy and obliged them not to enter alliances hostile to Rome and not to wage offensive wars without consent of the Senate.

"[38] From the late 9th to the early 11th century, the empire developed by Charlemagne achieved hegemony in Europe, with dominance over France, most of Northern and Central Italy, Burgundy and Germany.

[40] However, with the arrival of the Age of Discovery and the Early modern period, they began to gradually lose their hegemony to other European powers.

In The Rise of the Qi Ye Ji Tuan and the Emergence of Chinese Hegemony Jayantha Jayman writes, "If we consider the Western dominated global system from as early as the 15th century, there have been several hegemonic powers and contenders that have attempted to create the world order in their own images."

"[43][44] In late 16th- and 17th-century Holland, the Dutch Republic's mercantilist dominion was an early instance of commercial hegemony, made feasible by the development of wind power for the efficient production and delivery of goods and services.

[45] In France, King Louis XIV (1638–1715) and (Emperor) Napoleon I (1799–1815) attempted true French hegemony via economic, cultural and military domination of most of Continental Europe.

"[48]These fluctuations form the basis for cyclical theories by George Modelski and Joshua S. Goldstein, both of whom allege that naval power is vital for hegemony.

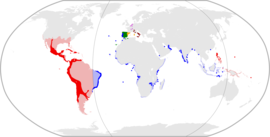

Both of these states' governments pursued policies to expand their regional spheres of influence, the US in Latin America and Japan in East Asia.

France, the UK, Italy, the Soviet Union and later Nazi Germany (1933–1945) all either maintained imperialist policies based on spheres of influence or attempted to conquer territory but none achieved the status of a global hegemonic power.

The result was that many countries, no matter how remote, were drawn into the conflict when it was suspected that their government's policies might destabilize the balance of power.

Reinhard Hildebrandt calls this a period of "dual-hegemony", where "two dominant states have been stabilizing their European spheres of influence against and alongside each other.

[53][54] This theory is heavily contested in academic discussions of international relations, with Anna Beyer being a notable critic of Nye and Mearsheimer.

[56]The French Socialist politician Hubert Védrine in 1999 described the US as a hegemonic hyperpower, because of its unilateral military actions worldwide.

[57] Pentagon strategist Edward Luttwak, in The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire,[58] outlined three stages, with hegemonic being the first, followed by imperial.

[61] In the historical writing of the 19th century, the denotation of hegemony extended to describe the predominance of one country upon other countries; and, by extension, hegemonism denoted the Great Power politics (c. 1880s – 1914) for establishing hegemony (indirect imperial rule), that then leads to a definition of imperialism (direct foreign rule).

In the early 20th century, the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci used the idea of hegemony to talk about politics within a given society.

[66] Beyer analysed the contemporary hegemony of the United States at the example of the Global War on Terrorism and presented the mechanisms and processes of American exercise of power in 'hegemonic governance'.

For him, hegemony was the most common order in history (historical "optimum") because many provinces of "frank" empires were under hegemonic rather than imperial rule.

Watson summarized his life-long research: There was a spectrum of political systems ranging between multiple independent states and universal empire.

The further a political system evolved towards one of the extremes, the greater was the gravitational pull towards the hegemonic center of the spectrum.

Coercive hegemons exert their economic or military power to discipline unruly or free-riding countries in their sphere of influence.

Realist international relations scholars argue that unipolarity is rooted in the superiority of U.S. material power since the end of the Cold War.

[87] Academics have argued that in the praxis of hegemony, imperial dominance is established by means of cultural imperialism, whereby the leader state (hegemon) dictates the internal politics and the societal character of the subordinate states that constitute the hegemonic sphere of influence, either by an internal, sponsored government or by an external, installed government.

[93] Adopted from the work of Gramsci and Stuart Hall, hegemony with respect to media studies refers to individuals or concepts that become most dominant in a culture.

Building on Gramsci's ideas, Hall stated that the media is a critical institution for furthering or inhibiting hegemony.