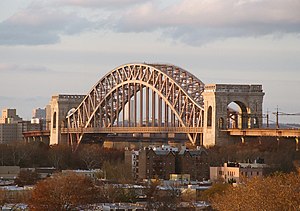

Hell Gate Bridge

A four-span inverted bowstring truss bridge, measuring 1,154 feet (352 m), carries the railroad tracks across Little Hell Gate, a former stream between Randalls and Wards Islands.

[5] Passengers traveling along the modern-day Northeast Corridor had to take a ferry from New Jersey and walk across Manhattan to Grand Central Terminal, or vice versa, to continue their journey.

[3][7] Throughout the 1890s, the New York State Legislature considered various bills that would give the NYCR a franchise to construct a bridge from Long Island to the U.S. mainland, but to no avail.

[2][47] His assistant Othmar Ammann wrote that the arch design would allow the bridge to serve as a figurative portal to the Port of New York and New Jersey.

[66] The PRR agreed to buy the last piece of land for the Queens approach that July,[70] at which point the cost of the bridge had increased to $25 million.

[92] Masonry contracts were awarded to Patrick Ryan (who partnered with U.S. Realty to build the Hell Gate spans' towers[93]), as well as Arthur McMullin and T. A.

[96][86] By July 1913, some of the piers and retaining walls for the Bronx and Queens viaducts had been constructed, and contractors had installed temporary plants on Randalls and Wards Islands.

[110] During a site visit in mid-1914, a local civic group noted that a temporary span had been finished across Bronx Kill and that piers were being built within the riverbed of Little Hell Gate.

[117] One thousand workers and 40 engineers began installing the steelwork of the arch in November 1914;[118] many of the laborers were Mohawk Native American ironworkers from Quebec and upstate New York.

[163] Meanwhile, the Port of New York Authority, which sought to increase the number of freight trains that used the Hell Gate Bridge,[164] hosted hearings in late 1924 to determine whether New York Central freight trains should be allowed to use the bridge,[150] The Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce and Long Island shippers endorsed the proposal,[165][166] while the LIRR, NH, and PRR opposed it.

[169] The order was modified to exclude freight to and from New England,[170] but the PRR and NH still refused to allow the New York Central to use the bridge after thirty days.

[208] The New Jersey car float was closed for an extended period during the 1970s, making the Hell Gate Bridge the only way for freight trains to get to and from Long Island during that time.

[212] The upgrades included modifications to allow double-stack freight trains to use the Hell Gate Bridge, thereby reducing the need for cargo trucks to travel through the city.

[217] City councilman Peter Vallone Sr. and U.S. representative Mario Biaggi advocated for Amtrak to repair the viaducts, saying the conditions threatened local residents' lives.

[238] Providence and Worcester Railroad freight trains carrying stone from quarries in Connecticut began using the bridge in 1996 to reach Long Island.

[236] Debris still fell from the bridge's approach viaducts due to both vandalism and general neglect,[243][244] and Vallone said in 2001 that the paint had started to peel off.

[247] In 2002, state government officials announced plans to spend $11.8 million to replace the bridge's freight track so it could support heavier trains.

[237][253] By early 2016, several local politicians were advocating for Amtrak to repaint the bridge in advance of its centennial, citing the fact that various parts of the spans had become discolored.

[94][275][276] The decks of each span are all made of concrete panels, which carry track beds with ballast; this was intended to reduce noise pollution and is unusual for a railroad bridge.

[261] Northwest of the Hell Gate span, the viaduct curves about 90 degrees to the northeast,[274] running along the east side of Wards and Randalls Islands.

[2][60] The metal piers were changed to concrete both because the Municipal Art Commission disapproved of the steel-lattice design,[261] and because there were concerns that the islands' prisoners and psychiatric patients could escape by climbing the trestles.

[292] The height of the arch above Hell Gate required that the line be placed on an elevated viaduct between Long Island City and Port Morris.

[295] The western ramp crosses over the Port Morris Branch's former eastern pair of tracks from 132nd to 133rd Street and is supported by large steel cross-girders.

The gravel and sand could not accommodate loads of more than 3 short tons per square foot (29 t/m2), so the Queens viaduct is supported by especially wide concrete piers.

[303] The bridge's two western tracks are part of the Hell Gate Line and are used for Acela Express and Northeast Regional service between New York and Boston.

[319] The Triboro RX plan was scaled down after the MTA determined that it would not be feasible to operate rapid transit on the bridge when Penn Station Access was finished.

[183] As a result of electrification, freight trains from Bay Ridge could travel as far east as Cedar Hill Yard in New Haven, Connecticut, without stopping.

[330][331] Just south of the bridge's Queens terminus, the Hell Gate Line transitions to Amtrak's 12 kV, 25 Hz traction power system, as that part of the route was electrified by the PRR.

[97] Hornbostel said the main span would "form a veritable triumphal arch at the northerly entrance of the Port of New York",[86] while the Railway Gazette called the project "second in interest only to the Quebec Bridge" due to its length.

[356] When the bridge was completed, the architect Hugh Ferriss drew a cover for the Queens Chamber of Commerce's monthly magazine Queensborough, which depicted the main span.