Helvetic Republic

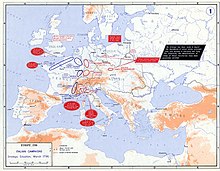

It was created following the French invasion and the consequent dissolution of the Old Swiss Confederacy, marking the end of the ancien régime in Switzerland.

[4] Throughout its existence, the republic incorporated most of the territory of modern Switzerland, excluding the cantons of Geneva and Neuchâtel and the old Prince-Bishopric of Basel.

[1] The Swiss Confederacy, which until then had consisted of self-governing cantons united by a loose military alliance (and ruling over subject territories such as Vaud), was invaded by the French Revolutionary Army and turned into an ally known as the "Helvetic Republic".

[5][6] Resistance was strongest in the more traditional Catholic cantons, with armed uprisings breaking out in spring 1798 in the central part of Switzerland.

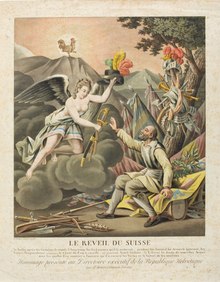

The French and Helvetic armies suppressed the uprisings, but opposition to the new government gradually increased over the years, as the Swiss resented their loss of local democracy, the new taxes, the centralization and the hostility to religion.

[citation needed] In Swiss history, the Helvetic Republic represents an early attempt to establish a centralized government in the country.

The French Republican armies enveloped Switzerland on the grounds of "liberating" the Swiss people, whose own system of government was deemed feudal, especially for annexed territories such as Vaud.

In response, the Cantons of Uri, Schwyz and Nidwalden raised an army of about 10,000 men led by Alois von Reding to fight the French.

Reding besieged French-controlled Lucerne and marched across the Brünig pass into the Berner Oberland to support the armies of Bern.

At the same time, the French General Balthasar Alexis Henri Antoine of Schauenburg marched out of occupied Zürich to attack Zug, Lucerne and the Sattel pass.

[8] On 13 May, Reding and Schauenburg agreed to a cease-fire, the terms of which included the rebel cantons merging into a single one, thus limiting their effectiveness in the central government.

Leading groups split into the Unitaires, who wanted a united republic, and the Federalists, who represented the old aristocracy and demanded a return to cantonal sovereignty.

Although the Federalist representatives formed a minority at the conciliation conference, known as the "Helvetic Consulta", Bonaparte characterised Switzerland as federal "by nature" and considered it unwise to force the country into any other constitutional framework.

In the post-Napoleonic era, the differences between the cantons (varying currencies and systems of weights and measurements) and the perceived need for better co-ordination between them came to a head and culminated in the Swiss Federal Constitution of 1848.

[12] Carl Hilty described the period as the first democratic experience in Swiss territory, while within conservatism it is seen as a time of national weakness and loss of independence.