Henri-Charles de Beaumanoir of Lavardin

In September 1669, even before he took up his official duties, the Duke of Chaulnes had regulated the enrolment of Breton sailors, and, at his request, the States of Brittany had created a commission to proceed with a naval armament of the coasts of Saint-Malo.

[2] Between March and September 1675, the West of France experienced a series of uprisings linked to an increase in taxes, including that of stamped paper, required for authentic acts.

On May 3, the arrival of the Duke of Chaulnes intensified the legal proceedings, as he was the bearer of orders from the king calling for the greatest severity against the rioters of April 18; three men injured during the disturbances were seized at Saint-Yves hospital.

[16] The Duke of Chaulnes and the Marquis of Lavardin then began a tight game: On the one hand, by demonstrating the threat of intervention by royal troops, they sought to bring the towns and notables back to obedience, and on the other hand, they hoped that a rapid return to calm would make it possible to avoid – or at least shorten – the entry of the royals into Brittany, in order to protect the province from the complications that would result from it – accommodation for the soldiers, subsistence costs for the troops, exactions by the soldiery, etc.

[19] The numerous letters that Lavardin sent to Colbert, Seignelay and Louvois highlight the voluntarism of the local authorities and underline the recovery of control by the Duke of Chaulnes; these documents have been used extensively to study the stamped paper revolt, and in particular the situation in Nantes.

[19][20] On Chaulnes' request, the commander of the cavalry of maréchaussée made them turn back; however, Lord Ervé, at the head of the detachment of the Crown regiment, ignored the duke's warnings and continued his march on Nantes.

[21] As for the repressive measures taken by the king's officers, they were relatively successful;[22] thus, of the five most involved "seditionists" that Chaulnes ordered to be arrested, only one of them, Goulven Saläun – who had distinguished himself by climbing the Bouffay belfry – was hanged on May 27 after a questioning and a two-day trial, the others having fled.

[23] On the other hand, public order, which had been damaged by the revolt, was restored: on 26 May, the tobacco and tin office was re-established; on 1 June, the Marquis de Lavardin reported that the control of stamped paper was going well; Louvois was informed that calm reigned in Nantes.

[25] As the only master of the town, the lieutenant-general continued to try to show severity; at the beginning of June, he obtained the departure of some inhabitants against whom the evidence was insufficient to justify a conviction; one of the prisoners died of his wounds, which allowed the marquis to claim that justice was being done.

Henri-Charles de Beaumanoir, still the master of the game in Nantes, watched with displeasure as the soldiers moved eastwards where he owned his lands of Lavardin, and which he feared would be ravaged by the repression.

[29] On June 29, the feast of Saint Peter, Lavardin, wishing to confirm his return to control of the city, had guards in his livery placed in the choir of the cathedral, which caused unrest in the population, as this was an unprecedented event – it was a royal privilege.

At that time, franchises were rights held in Rome by the ambassadors of certain European powers, which allowed them to exempt the area surrounding their residence from Roman jurisdiction in matters of customs and justice.

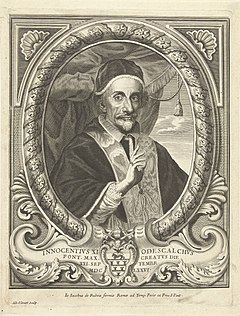

[34] In 1679, the Pontiff warned the French court that, as long as François Annibal II d'Estrées was ambassador, France's franchises would be respected, but that the new holder could only take up his duties on condition that he renounced them.

[37][38] The Pope obtained the submission - often grudgingly - of the other European courts, but Louis XIV retorted to the nuncio "that God had established him to serve as an example and rule to others, and not to imitate them"; nevertheless, Lavardin's departure was suspended and used to assemble a military escort to keep the Papal forces at bay.

[40] The arrival of the Marquis of Lavardin was marked by great pomp and circumstance, with his soldiers marching in with weapons in hand; the officers of the papal customs were dissuaded by his escort from infringing on the ambassador's rights.

[42] The first measures taken by Lavardin were successful: the sbirri were kept away, a hundred criminals were chased away from the vicinity of the Piazza Farnese, the crossing points in the district were carefully controlled to avoid abuses, and the ambassador's soldiers behaved impeccably with the population.

[41] On December 13, the Marquis informed the chapter of the Basilica of St John Lateran that he intended to attend the service in memory of Henry IV and to receive the honours due to a French ambassador.

[N 6][40] On December 27, 1687, Lavardin published a Protest[46] in which he asserted that as ambassador of "His Most Christian Majesty" he was "exempt from all ecclesiastical censures, as long as he is clothed in this character and carries out the orders of the King his master",[47] a long-standing Gallican claim.

The situation worsened further in August 1688 when the Pope refused to confirm Cardinal of Fürstenberg – France's candidate – to the electorate of Cologne, and appeared to be siding with the League of Augsburg in the European struggle against the monarchy of Louis XIV.

The situation in the streets of Rome also contributed to making the two sovereigns irreconcilable: after Lavardin's soldiers had beaten up some sbirri in June 1688, the Roman justice system condemned them to death in absentia and put a price on their heads.

On September 13, 1688, faced with the intransigence of Innocent XI, he ordered the invasion of Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin by French troops; preparations for a landing at Civitavecchia became more precise.

Many Italian nobles, not least the Duke of Bracciano – head of the House of Orsini – disassociated themselves from the French party, and the ambassador was only frequented by a few loyalists, including Christine of Sweden.

On 14 April 1689, Louis XIV accepted;[54] this decision was due as much to the fact that he feared incidents as to a desire to appease the Holy See, made necessary by the situation in Europe.

Brittany was the last French province to be endowed with such an agent of the king; the monarch surely felt that European tensions justified this increase in absolutism in a country of states within reach of the English coast.

In 1695, Louis XIV obtained his resignation and replaced him with the Count of Toulouse, his legitimate bastard son; the latter renounced direct administration of the province and only went there on royal request.

[59] On the other hand, he suffered a setback in 1696: having opposed the establishment of a patrol in Rennes on the grounds that he was not going to re-arm a town that he had disarmed during the revolt of 1675, he was proven wrong by the Council of Finance and the Controller General overruled his opinion, which was deemed anachronistic.

[62] The disgrace of the Duke of Chaulnes, threatened with repayment of unduly collected duties, led Lavardin to defend the rights of the governors, with the help of the States of Brittany.

[63] This thesis was strongly opposed by Jean-Baptiste-Henri of Valincour, Secretary General of the Navy, who pointed out that there was no mention of governors in the above-mentioned acts; he also defended the position that the vice-admirals of Brittany had always been appointed by the admirals of France.

[64] Eight months after the appointment of the Earl of Toulouse as governor, Louis XIV asked the States of Brittany to justify the province's claims, while Valincour was given the responsibility of defending the French admiral.

[65] It was not until six years later that, on May 30, 1701, on the advice of a commission and his ministers, Louis XIV issued a decree confirming the governors in the rights of the admiralty of Brittany and maintaining the claims of the Marquis of Lavardin.