Henrietta Maria of France

Henrietta Maria of France (French: Henriette Marie; 25 November[1] 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until his execution on 30 January 1649.

As Philip was aware, such terms were unacceptable, and when Charles returned to England in October, he and Buckingham demanded King James declare war on Spain.

A Francophile and godson of Henry IV of France, Holland strongly favoured a marriage with Henrietta Maria, the terms of which were negotiated by James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle.

Her arms were long and lean, her shoulders uneven, and some of her teeth were coming out of her mouth like tusks....[8] She did, however, have pretty eyes, nose, and a good complexion..."[8] A proxy marriage was held at Notre-Dame de Paris on 1 May 1625, where Duke Claude of Chevreuse stood as proxy for Charles, shortly after Charles succeeded as king, with the couple spending their first night together at St Augustine's Abbey near Canterbury on 13 June 1625.

A suggestion she be crowned by Daniel de La Mothe-Houdancourt, the bishop of Mende who accompanied her to England, was unacceptable, although she was allowed to watch her husband's coronation at a discreet distance.

Henrietta Maria has been criticised as being an "intrinsically apolitical, undereducated and frivolous"[13] figure during the 1630s; others have suggested that she exercised a degree of personal power through a combination of her piety, her femininity, and her sponsorship of the arts.

In July 1626, she caused huge controversy by stopping at Tyburn to pray for Catholics executed there[18] and later tried to convert her Calvinist nephew Prince Rupert during his stay in England.

"[21] The new queen brought with her a huge quantity of expensive possessions, including jewellery, ornate clothes, 10,000 livres' worth of plate, chandeliers, pictures and books.

[25] Despite these reforms and gifts from the king, her spending continued at a high level; in 1627, she was secretly borrowing money,[26] and her accounts show large numbers of expensive dresses purchased during the pre-war years.

[27] There were fears over her health, and in July 1627 she travelled with her physician Théodore de Mayerne to take the medicinal spring waters at Wellingborough in Northamptonshire, while Charles visited Castle Ashby House.

On 11 January 1645, for example, Charles wrote, "And dear Heart, thou canst not but be confident that there is no danger which I will not hazzard, or pains that I will not undergo, to enjoy the happiness of thy company.

[54] The traditional perspective on the Queen has suggested that she was a strong-willed woman who dominated her weaker-willed husband for the worse; the historian Wedgwood, for example, highlights Henrietta Maria's steadily increasing ascendancy over Charles, observing that "he sought her advice on every subject, except religion" and indeed complained that he could not make her an official member of his council.

Henrietta Maria's strong views on religion and social life at the court meant that, by 1642, she had become a "highly unpopular queen who apparently never successfully commanded intense personal respect and loyalty from most of her subjects".

[36] To some extent, it worked, with numerous conversions amongst Henrietta Maria's circle; historian Kevin Sharpe argues that there may have been up to 300,000 Catholics in England by the late 1630s – they were certainly more open in court society.

[64] In the late 1630s, the lawyer William Prynne, popular in Puritan circles, also had his ears cut off for writing that women actresses were notorious whores, a clear insult to Henrietta Maria.

[70] The arrest was bungled, and Pym and his colleagues escaped Charles's soldiers, possibly as a result of a tip-off from Henrietta Maria's former friend Lucy Hay.

[71] The situation was steadily moving towards open war, and in February Henrietta Maria left for The Hague, both for her own safety and to attempt to defuse public tensions about her Catholicism and her closeness to the king.

Henrietta Maria focused on raising money on the security of the royal jewels, and on attempting to persuade Prince Frederick Henry of Orange and King Christian IV of Denmark to support Charles's cause.

[76] Henrietta Maria was finally partially successful in her negotiations, particularly for the smaller pieces, but she was portrayed in the English press as selling off the crown jewels to foreigners to buy guns for a religious conflict, adding to her unpopularity at home.

Part of the rashness of the following decisions were partially due to the desire to rejoin Charles I in person, as his recent decision-making and disregard of her advising caused her to grow very concerned.

[79] The pursuing naval vessels then bombarded the town, forcing the royal party to take cover in neighbouring fields; Henrietta Maria returned under fire, however, to recover her pet dog Mitte which had been forgotten by her staff.

[86] In March, Henry Marten and John Clotworthy forced their way into the chapel with troops and destroyed the altarpiece by Rubens,[86] smashed many of the statues and made a bonfire of the queen's religious canvases, books and vestments.

[93] Waller would pursue and hold down the king and his forces, while Essex would strike south to Exeter with the aim of capturing Henrietta Maria and thereby acquiring a valuable bargaining counter over Charles.

[94] The Queen was in considerable pain and distress,[95] but decided that the threat from Essex was too great; leaving newborn Henrietta in Exeter because of the risks of the journey,[96] she stayed at Pendennis Castle, then took to sea from Falmouth in a Dutch vessel for France on 14 July.

[99] The campaigns of 1645 went poorly for the Royalists, however, and the capture, and subsequent publishing, of the correspondence between Henrietta Maria and Charles in 1645 following the Battle of Naseby proved hugely damaging to the royal cause.

[102] With the support of Anne of Austria and the French government, Henrietta Maria settled in Paris, appointing as her chancellor, the eccentric Sir Kenelm Digby, and forming a Royalist court in exile at the Chateau-Neuf de Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

[109] The result was the Second Civil War, which despite Henrietta Maria's efforts to send it some limited military aid,[110] ended in 1648 with the defeat of the Scots and Charles's capture by Parliamentary forces.

More death was to follow: on Christmas Eve, Henrietta's elder daughter Mary also died of smallpox in London, leaving behind a 10-year-old son, the future William III of England.

Shortly afterwards, she died at the Château de Colombes,[124] near Paris, having taken an excessive quantity of opiates as a painkiller on the advice of Louis XIV's doctor, Antoine Vallot for having a serious lung infection at the time.

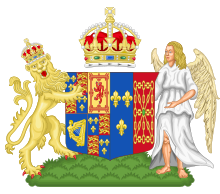

The arms of Henry IV were: Azure, three fleurs de lys Or (France); impaling Gules, a cross a saltire and an orle of chains linked at the fess point with an amulet vert (Navarre).