Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

He gradually developed a reputation for supporting public causes, such as educational reform and the abolition of slavery worldwide, and he was entrusted with running the Queen's household, office and estates.

Prince Albert was born on 26 August 1819 at Schloss Rosenau, near Coburg, Germany, the second son of Ernest III, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and his first wife, Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg.

[6] Albert and his elder brother, Ernest, spent their youth in close companionship, which was marred by their parents' turbulent marriage and eventual separation and divorce.

[15] She wrote, "[Albert] is extremely handsome; his hair is about the same colour as mine; his eyes are large and blue, and he has a beautiful nose and a very sweet mouth with fine teeth; but the charm of his countenance is his expression, which is most delightful.

[26] Initially Albert was not popular with the British public; he was perceived to be from an impoverished and undistinguished minor state, barely larger than a small English county.

[39] He was gaining public support as well as political influence, which showed itself practically when, in August, Parliament passed the Regency Act 1840 to designate him regent in the event of Victoria's death before their child reached the age of majority.

All nine children survived to adulthood, which was remarkable for the era; biographer Hermione Hobhouse credited the healthy running of the nursery on Albert's "enlightened influence".

[42] After the 1841 general election, Melbourne was replaced as prime minister by Sir Robert Peel, who appointed Albert chairman of the royal commission in charge of redecorating the new Palace of Westminster.

The commission's work was slow, and the palace's architect, Charles Barry, took many decisions out of the commissioners' hands by decorating rooms with ornate furnishings that were treated as part of the architecture.

Among his notable acquisitions were early German and Italian paintings—such as Lucas Cranach the Elder's Apollo and Diana and Fra Angelico's St Peter Martyr—and contemporary pieces from Franz Xaver Winterhalter and Edwin Landseer.

[49] By 1844, Albert had managed to modernise the royal finances and, through various economies, had sufficient capital to purchase Osborne House on the Isle of Wight as a private residence for their growing family.

[54] Unlike many landowners who approved of child labour and opposed Peel's repeal of the Corn Laws, Albert supported moves to raise working ages and free up trade.

[55] In 1846, Albert was rebuked by Lord George Bentinck when he attended the debate on the Corn Laws in the House of Commons to give tacit support to Peel.

The tenant of Balmoral, Sir Robert Gordon, died suddenly in early October, and Albert began negotiations to take over the lease from the owner, the Earl Fife.

According to historian G. M. Trevelyan, regarding the Prince and home affairs: His influence over the Queen was on the whole liberal; he greatly admired Peel, was a strong free-trader, and took more interest in scientific and commercial progress, and less in sport and fashion than was at all popular in the best society.

[73] Albert thought such talk absurd and quietly persevered, trusting always that British manufacturing would benefit from exposure to the best products of foreign countries.

[77] The same year, he was appointed to several of the offices left vacant by the death of the Duke of Wellington, including the mastership of Trinity House and the colonelcy of the Grenadier Guards.

As public outrage at the Russian action continued, false rumours circulated that Albert had been arrested for treason and was being held prisoner in the Tower of London.

Recognised as a supporter of education and technological progress, he was invited to speak at scientific meetings, such as the memorable address he delivered as president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science when it met at Aberdeen in 1859.

[88] His espousal of science met with clerical opposition; he and Palmerston unsuccessfully recommended a knighthood for Charles Darwin, after the publication of On the Origin of Species, which was opposed by the Bishop of Oxford.

His secular compositions included a cantata, L'Invocazione all'armonia, and Melody for the Violin, which Yehudi Menuhin later described as "pleasant music without presumption".

[100] His steadily worsening medical condition led to a sense of despair; the biographer Robert Rhodes James describes Albert as having lost "the will to live".

Two of Albert's young cousins, King Pedro V of Portugal and his brother Ferdinand, died of typhoid fever within five days of each other in early November.

[106] On top of that news, Albert was informed that gossip was spreading in gentlemen's clubs and the foreign press that the Prince of Wales was involved with Nellie Clifden.

[111] In a few hours, he revised the British demands in a manner that allowed the Lincoln administration to surrender the Confederate commissioners who had been seized from the Trent and to issue a public apology to London without losing face.

The key idea, based on a suggestion from The Times, was to give Washington the opportunity to deny that it had officially authorised the seizure and thereby to apologise for the captain's mistake.

[117] The widowed Victoria never recovered from Albert's death; she entered into a deep state of mourning and wore black for the rest of her life.

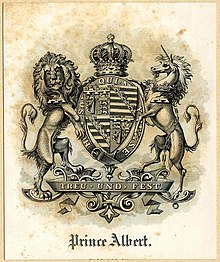

[26][161] They are blazoned: "Quarterly, 1st and 4th, the Royal Arms, with overall a label of three points Argent charged on the centre with cross Gules; 2nd and 3rd, Barry of ten Or and Sable, a crown of rue in bend Vert".

Albert's Garter stall plate displays his arms surmounted by a royal crown with six crests for the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha; these are from left to right: 1.

Prince Albert's 42 grandchildren included four reigning monarchs: King George V of the United Kingdom; Wilhelm II, German Emperor; Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse; and Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and five consorts of monarchs: Empress Alexandra of Russia and Queens Maud of Norway, Sophia of Greece, Victoria Eugenie of Spain, and Marie of Romania.