Henry Percy, 5th Earl of Northumberland

In 1497 he served in the royal army against the Cornish rebels, and fought at the Battle of Blackheath; on 14 May 1498 he received livery of his lands, and entered into the management of his various castles and estates.

On his various retinues of servants and followers he spent no less than £1,500 a year, and as the remainder had to meet all such expenses as his journeys to the court, and as his lifestyle was extraordinarily magnificent, he was soon in debt.

From Calais he went to the siege of Thérouanne and at the Battle of the Spurs he commanded the "showrers and forridors", Northumberland men on light geldings.

On a charge of interfering with the king's prerogative concerning wardships, he was cast into the Fleet Prison in 1516, possibly only so that Wolsey might obtain the credit of getting him out.

Shrewsbury had been anxious to marry-off his daughter to a son of Buckingham's, but having disputed about money matters, the parents broke off the match.

In June 1517 Northumberland met Queen Margaret of Scotland at York to conduct her on her way home, which duty he had undertaken with reluctance, doubtless from want of money, and his wife was excused attendance.

Wolsey in 1519, in a letter to the king, expressed suspicions of his loyalty,[10] but he escaped the fate of the Duke of Buckingham, and was at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, where he was a judge of the lists.

In 1523 he made an inroad into Scotland, and was falsely accused by Lord Dacre of going to war with the Crosskeys of York, a royal badge, on his banner; he cleared himself easily enough.

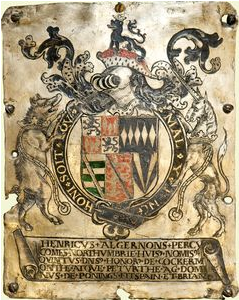

In the north window there was a stained glass depiction of the 4th Earl with his wife, Maud Herbert (also buried at Beverley,) and eight children.

This was drawn by Sir William Dugdale for his 'Book of Monuments' in 1640-1641 and the drawing, with others of Beverley, is preserved in the British Library (MS Lansdowne 896, ff35-39.)

The 5th Earl's monument was drawn for the Wriothesley Heraldic Collections, 'Collections Relating to Funerals', which are also preserved in the British Library, London.

Northumberland displayed magnificence in his tastes, and being one of the richest magnates of his day,[3] kept a very large household establishment, and was fond of building.