Henry Box Brown

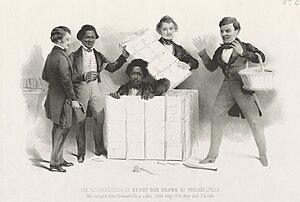

This is an accepted version of this page Henry Box Brown (c. 1815 – June 15, 1897)[1] was an enslaved man from Virginia who escaped to freedom at the age of 33 by arranging to have himself mailed in a wooden crate in 1849 to abolitionists in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

[1] Henry Brown was born into slavery in 1815 on a plantation called Hermitage in Louisa County, Virginia.

[1]a Minister in North Carolina[7] With the help of James C. A. Smith, a free black man,[4] and a sympathetic white shoemaker named Samuel A. Smith (no relation), Brown devised a plan to have himself shipped in a box to a free state by the Adams Express Company, known for its confidentiality and efficiency.

[6] Smith went to Philadelphia to consult members of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society on how to accomplish the escape, meeting with minister James Miller McKim, William Still, and Cyrus Burleigh.

They advised him to mail the box to the office of Quaker merchant Passmore Williamson, who was active with the Vigilance Committee.

It was lined with baize, a coarse woolen cloth, and he carried only a small portion of water and a few biscuits.

[4] Brown later wrote that his uncertain method of travel was worth the risk: "if you have never been deprived of your liberty, as I was, you cannot realize the power of that hope of freedom, which was to me indeed, an anchor to the soul both sure and steadfast.

The box was received by Williamson, McKim, William Still, and other members of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee on March 30, 1849, attesting to the improvements in express delivery services.

[9] In addition to celebrating Brown's inventiveness, as noted by Hollis Robbins, "the role of government and private express mail delivery is central to the story and the contemporary record suggests that Brown's audience celebrated his delivery as a modern postal miracle."

The government postal service had dramatically increased communication and, despite southern efforts to control abolitionist literature, mailed pamphlets, letters and other materials reached the South.

[6] Cheap postage, Frederick Douglass observed in The North Star, had an "immense moral bearing".

[6]Brown's escape highlighted the power of the mail system, which used a variety of modes of transportation to connect the East Coast.

The first, written with the help of Charles Stearns and conforming to expectations of the slave narrative genre,[6] was published in Boston in 1849.

In his Narrative, he offers a cure for slavery, suggesting that slaves should be given the vote, a new president should be elected, and the North should speak out against the "spoiled child" of the South.

[14] In the 1860s, he began performing as a magician with acts as a mesmerist and conjuror, under the show names of "Prof. H. Box Brown" and the "African Prince".

[15] While in England in 1855, Brown married Jane Floyd, a White Cornish tin worker's daughter, and began a new family.

[1] As the scholar Martha J. Cutter first documented in 2015, Henry Box Brown died in Toronto on June 15, 1897.

[1] This information is not definitive, however, because passenger records in this period of ships returning to Canada contain few specific details about their occupants beyond first and last name and gender.

Samuel Alexander Smith attempted to ship more enslaved people from Richmond to liberty in Philadelphia, but was discovered and arrested.