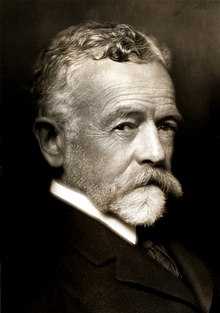

Henry Cabot Lodge

Defunct Newspapers Journals TV channels Websites Other Congressional caucuses Economics Gun rights Identity politics Nativist Religion Watchdog groups Youth/student groups Miscellaneous Other Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 – November 9, 1924) was an American politician, historian, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts.

He grew up on Boston's Beacon Hill and spent part of his childhood in Nahant, Massachusetts, where he witnessed the 1860 kidnapping of a classmate and gave testimony leading to the arrest and conviction of the kidnappers.

In 1874, he graduated from Harvard Law School, and was admitted to the bar in 1875, practicing at the Boston firm now known as Ropes & Gray.

[8] After traveling through Europe, Lodge returned to Harvard, and, in 1876, became one of the earliest recipients of a PhD in history from an American university.

[16] Along with his close friend Theodore Roosevelt, Lodge was sympathetic to the concerns of the Mugwump faction of the Republican Party.

The Democrats had made significant gains in Massachusetts and the Republicans were split between the progressive and conservative wings, with Lodge trying to mollify both sides.

He rarely campaigned on his own behalf but now he made his case, explaining his important roles in civil service reform, maintaining the gold standard, expanding the Navy, developing policies for the Philippine Islands, and trying to restrict immigration by illiterate Europeans, as well as his support for some progressive reforms.

Lodge voted for Taft instead of Roosevelt; after Woodrow Wilson won the election the Lodge-Roosevelt friendship resumed.

Although the proposed legislation was supported by President Benjamin Harrison, the bill was blocked by filibustering Democrats in the Senate.

[23] Lodge did not change his position even after the junior senator from Massachusetts, John Weeks, lost his seat in 1918 due to his opposition to equal suffrage.

[24] Lodge was a strong backer of U.S. intervention in Cuba in 1898, arguing that it was the moral responsibility of the United States to do so: Of the sympathies of the American people, generous, liberty-loving, I have no question.

The great power of the United States, if it is once invoked and uplifted, is capable of greater things than that.Following American victory in the Spanish–American War, Lodge came to represent the imperialist faction of the Senate, those who called for the annexation of the Philippines.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, significant numbers of immigrants, primarily from Eastern and Southern Europe, were migrating to industrial centers in the United States.

Lodge argued that unskilled foreign labor was undermining the standard of living for American workers, and that a mass influx of uneducated immigrants would result in social conflict and national decline.

In an address to the New England Society of Brooklyn in 1888, Lodge stated: Let every man honor and love the land of his birth and the race from which he springs and keep their memory green.

[32] He proposed that the United States should temporarily shut out all further entries, particularly persons of low education or skill, to more efficiently assimilate the millions who had already come.

From 1907 to 1911, he served on the Dillingham Commission, a joint congressional committee established to study the era's immigration patterns and make recommendations to Congress based on its findings.

Lodge was a staunch advocate of entering World War I on the side of the Allied Powers, attacking President Woodrow Wilson for poor military preparedness and accusing pacifists of undermining American patriotism.

He contended that Germany needed to be militarily and economically crushed and saddled with harsh penalties so that it could never again be a threat to the stability of Europe.

Lodge appealed to the patriotism of American citizens by objecting to what he saw as the weakening of national sovereignty: "I have loved but one flag and I can not share that devotion and give affection to the mongrel banner invented for a league."

[38]Lodge was also motivated by political concerns; he strongly disliked Wilson personally[39] and was eager to find an issue for the Republican Party to run on in the presidential election of 1920.

Lodge rejected an open-ended commitment that might subordinate the national security interests of the United States to the demands of the League.

He especially insisted that Congress must approve interventions individually; the Senate could not, through treaty, unilaterally agree to enter hypothetical conflicts.

[3] Cooper and Bailey suggest that Wilson's stroke on September 25, 1919, had so altered his personality that he was unable to effectively negotiate with Lodge.

"[43] The Treaty of Versailles went into effect, but the United States did not sign it and made separate peace with Germany and Austria-Hungary.

[3] Historians agree that the League was ineffective in dealing with major issues, but they debate whether American membership would have made much difference.

[46] In June 1922, he introduced the Lodge–Fish Resolution, to illustrate American support for the British policy in Palestine per the 1917 Balfour Declaration.

Historian George E. Mowry argues that: Henry Cabot Lodge was one of the best informed statesmen of his time, he was an excellent parliamentarian, and he brought to bear on foreign questions a mind that was at once razor sharp and devoid of much of the moral cant that was so typical of the age.

He was opportunistic, selfish, jealous, condescending, supercilious, and could never resist calling his opponent's spade a dirty shovel.

The other Regents considered Lodge to be a "distinguished colleague, whose keen, constructive interest in the affairs of the Institution led him to place his broad knowledge and large experience at its service at all times.