Heraclitus

Heraclitus, the son of Blyson, was from the Ionian city of Ephesus, a port on the Cayster River, on the western coast of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey).

[s][t][note 3] Heraclitus is traditionally considered to have flourished in the 69th Olympiad (504–501 BC),[11][a] but this date may simply be based on a prior account synchronizing his life with the reign of Darius the Great.

[1][note 4] However, this date can be considered "roughly accurate" based on a fragment that references Pythagoras, Xenophanes, and Hecataeus as older contemporaries, placing him near the end of the sixth century BC.

[a] Classicist Charles Kahn states: "Down to the time of Plutarch and Clement, if not later, the little book of Heraclitus was available in its original form to any reader who chose to seek it out.

Classicist John Burnet has argued that "it is not to be supposed that this division is due to [Heraclitus] himself; all we can infer is that the work fell naturally into these parts when the Stoic commentators took their editions of it in hand".

[25] The Stoic Cleanthes further divided philosophy into dialectics, rhetoric, ethics, politics, physics, and theology, and philologist Karl Deichgräber has argued the last three are the same as the alleged division of Heraclitus.

[27][28] Scholar Martin Litchfield West claims that while the existing fragments do not give much of an idea of the overall structure,[29] the beginning of the discourse can probably be determined,[note 6] starting with the opening lines, which are quoted by Sextus Empiricus: Of the logos being forever do men prove to be uncomprehending, both before they hear and once they have heard it.

[x] Heraclitus's style has been compared to a Sibyl,[3][30][31] who "with raving lips uttering things mirthless, unbedizened, and unperfumed, reaches over a thousand years with her voice, thanks to the god in her".

"[35] Also according to Diogenes Laërtius, Timon of Phlius called Heraclitus "the Riddler" (αἰνικτής; ainiktēs) a likely reference to an alleged similarity to Pythagorean riddles.

"[ba][note 8] Each substance contains its opposite, making for a continual circular exchange of generation, destruction, and motion that results in the stability of the world.

"[81] The Milesians before Heraclitus had a view called material monism which conceived of certain elements as the arche – Thales with water, Anaximander with apeiron, and Anaximenes with air.

[82][bj][bk] Pre-Socratic scholar Eduard Zeller has argued that Heraclitus believed that heat in general and dry exhalation in particular, rather than visible fire, was the arche.

[89] On yet another interpretation, Heraclitus is not a material monist explicating flux nor stability, but a revolutionary process philosopher who chooses fire in an attempt to say there is no arche.

[100][bq] According to Bertrand Russell, this was "obviously inspired by scientific reflection, and no doubt seemed to him to obviate the difficulty of understanding how the sun can work its way underground from west to east during the night".

"[117][ce] Heraclitus associates being awake with comprehension;[42] as Sextus Empiricus explains "It is by drawing in this divine reason in respiration that we become endowed with mind and in sleep we become forgetful, but in waking we regain our senses.

[ch] Heraclitus believed the soul is what unifies the body and also what grants linguistic understanding, departing from Homer's conception of it as merely the breath of life.

[ci][note 12] His own views on the afterlife remain unclear,[95] but Heraclitus did state: "There await men after they are dead things which they do not expect or imagine.

[126] Philosopher Gustav Teichmüller sought to prove Heraclitus was influenced by the Egyptians,[127][128] either directly, by reading the Book of the Dead, or indirectly through the Greek mystery cults.

[131] Heraclitus's writings have exerted a wide influence on Western philosophy, including the works of Plato and Aristotle, who interpreted him in terms of their own doctrines.

[141] To explain both characterizations by Plato and Aristotle, Cratylus may have thought continuous change warrants skepticism because one cannot define a thing that does not have a permanent nature.

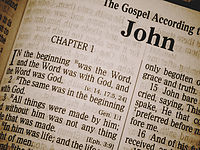

[87][80][162] The Stoics believed major tenets of their philosophy derived from the thought of Heraclitus; especially the logos, used to support their belief that rational law governs the universe.

[193] Modern interest in early Greek philosophy can be traced back to 1573, when French printer Henri Estienne (also known as Henricus Stephanus) collected a number of pre-Socratic fragments, including some forty of those of Heraclitus, and published them in Latin in Poesis philosophica.

[189] Additionally, in one scene of the play Portia assesses her potential suitors, and says of one County Palatine: "I fear he will prove the weeping philosopher when he grows old".

[204] French rationalist philosopher René Descartes read Montaigne and wrote in The Passions of the Soul that indignation can be joined by pity or derision, "So the laughter of Democritus and the tears of Heraclitus could have come from the same cause".

[84] The German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher was one of the first to collect the fragments of Heraclitus specifically and write them out in his native tongue, the "pioneer of Heraclitean studies".

[128][220][231] Fellow Young Hegelian Karl Marx compared Lasalle's work to that of "a schoolboy"[232] and Vladimir Lenin accused him of "sheer plagiarism".

"[cv] The Irish author and classicist Oscar Wilde was influenced by art critic Walter Pater, a friend of Bywater's whose "pre-Socratic hero" was Heraclitus.

[259] Wittgenstein was known to read Plato[260] and in his return to philosophy in 1929 he made several remarks resembling those of Heraclitus: "The fundamental thing expressed grammatically: What about the sentence: One cannot step into the same river twice?

"[263][264] Aristotle's arguments for the law of non-contradiction, which he saw as refuting the position started by Heraclitus,[265] used to be considered authoritative, but have been in doubt ever since their criticism by Polish logician Jan Łukasiewicz, and the invention of many-valued and paraconsistent logics.

[266][267] Some philosophers such as Graham Priest and Jc Beall follow Heraclitus in advocating true contradictions or dialetheism,[47] seeing it as the most natural response to the liar paradox.