College of Arms

The heralds are appointed by the British Sovereign and are delegated authority to act on behalf of the Crown in all matters of heraldry, the granting of new coats of arms, genealogical research and the recording of pedigrees.

[12] The King empowered the College to have and use only one common seal of authority, and also instructed them to find a chaplain to celebrate mass daily for himself, Anne Neville, the Queen Consort, and his heir, Prince Edward.

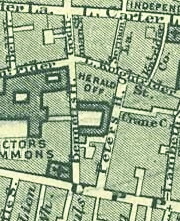

[5][7] The College was also granted a house named Coldharbour (formerly Poulteney's Inn) on Upper Thames Street in the parish of All-Hallows-the-Less, for storing records and living space for the heralds.

[15][16] The defeat and death of Richard III at Bosworth field was a double blow for the heralds, for they lost both their patron, the King, and their benefactor, the Earl Marshal, who was also slain.

[21] During his magnificent meeting with Francis I of France at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520, Henry VIII brought with him eighteen officers of arms, probably all he had, to regulate the many tournaments and ceremonies held there.

[23] Furthermore, Henry VIII's habit of raising ladies in the situation of subjects to queens, and then awarding them many heraldic augmentations, which also extended to their respective families, was considered harmful to the science of heraldry.

[11][26] The College found a patroness in Mary I, although it must have been embarrassing for both sides, after the heralds initially proclaimed the right of her rival Lady Jane Grey to the throne.

When King Edward VI died on 6 July 1553, Lady Jane Grey was proclaimed queen four days later, first in Cheapside then in Fleet Street by two heralds, trumpets blowing before them.

[30] The charter stated that the house would: "enable them [the College] to assemble together, and consult, and agree amongst themselves, for the good of their faculty, and that the records and rolls might be more safely and conveniently deposited.

[14] Derby Place's hearth tax bill from 1663, discovered in 2009 at the National Archives at Kew, showed that the building had about thirty-two rooms, which were the workplace as well as the home to eleven officers of arms.

[32][33] The long reign saw the College distracted by the many quarrels between Garter William Dethick, Clarenceux Robert Cooke and York Herald Ralph Brooke about their rights and annulments.

The heralds contributed significantly out of their own pockets; at the same time, they also sought subscriptions among the nobility, with the names of contributors recorded into a series of splendid manuscripts known as the Benefactors Books.

The Surveyor traced the leak back to a shed recently erected by Alderman Smith, owner of the Sugar House, who declared his readiness to do everything he could, but who actually did very little to rectify the situation.

[62] John Nash was at the same time laying out his plans for a new London, and, in 1822, the College, through the Deputy Earl Marshal, asked the government for a portion of land in the new districts on which to build a house to keep their records.

[75] Some of the members of the committee (a minority) wanted (like Burke thirty-four years earlier) to make officers of the College of Arms into "salaried civil servants of the state".

"[76] In 1905 the generous endowment from the Crown (as instituted by George IV) was stopped by the Liberal Government of the day as part of its campaign against the House of Lords and the class system.

[78] Sir Anthony Wagner writes that "The officers of these departments, no doubt, in the overconfident way of their generation, esteemed the College an anachronistic and anomalous institution overdue for reform or abolition.

The exhibition was opened by the Earl Marshal and ran from 28 June to 26 July, during which time it received more than 10,000 visitors, including the Duke (George VI) and Duchess of York (Elizabeth).

[80] In 1939 at the beginning of the Second World War the College's records were moved to Thornbury Castle in Gloucestershire, the home of Major Algar Howard (the Norroy King of Arms).

The barrier, consisting of a silken rope (in place of the ancient bar), is then removed and the detachment marches forward to meet the Lord Mayor and City Sheriffs, where the proclamation would be read.

This has been the case since 1673, when the authority of the Earl Marshal, which the heralds had challenged, was established by a royal declaration stating, among other things, that no patents of arms should be granted without his consent.

[105][108] Currently there are no set criteria for eligibility for a grant of arms; however the College recommends that "awards or honours from the Crown, civil or military commissions, university degrees, professional qualifications, public and charitable services, and eminence or good standing in national or local life" will be taken into account.

[clarification needed] Suitability rested on the phrase "eminent men"; originally the test applied was one of wealth or social status, as any man entitled to bear a coat of arms was expected to be a gentleman.

[105] The fees mainly go towards commissioning the artwork and calligraphy on the vellum Letters Patent, which must be done by hand and is in a sense a work of art in itself, plus other administrative costs borne by the heralds, and for the upkeep of the College.

Prior to the passage of this Act, anyone succeeding to a title in the peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, would prove their succession by a writ of summons to Parliament.

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet advised in 2018 that grants from the College of Arms were "well established as one way Australians can obtain heraldic insignia if they wish to do so", but that they had the same status as those by "a local artist, graphics studio or heraldry specialist".

[1][89] Thus the Earl Marshal became the head and chief of the College of Arms; all important matters concerning its governance, including the appointment of new heralds, must meet with his approval.

[131] John Anstis wrote that: "The Wearing the outward Robes of the Prince, hath been esteemed by the Consent of Nations, to be an extraordinary Instance of Favour and Honour, as in the Precedent of Mordecai, under a king of Persia.

The silver-gilt crown is composed of sixteen acanthus leaves alternating in height, inscribed with a line from Psalm 51 in Latin: Miserere mei Deus secundum magnam misericordiam tuam (KJV: Have mercy upon me O God according to thy lovingkindness).

In medieval times the kings of arms were required to wear their crowns and attend to the Sovereign on four high feasts of the year: Christmas, Easter, Whitsuntide and All Saint's Day.