Numbers 31

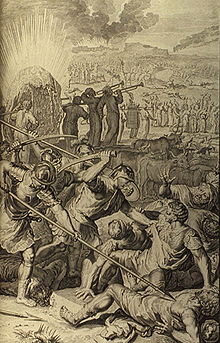

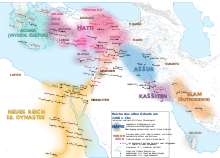

[1][2] Set in the southern Transjordanian regions of Moab and Midian, it narrates the Israelites waging war against the Midianites, commanded by Phinehas and Moses.

[3] Martin Noth argued that the author of chapter 31 was probably aware of the combined non-P/P(H) text (with the Moabite–Midianite connection) in chapter 25, and probably knew the entire composite Pentateuch, therefore Numbers 31 was written in whole or in part by an author writing later than regular P.[3] Israel Knohl (1995) argued Numbers 31 was in fact part of the Holiness code (H), which was later added to the Priestly source.

When Balaam saw that he could not curse the children of Israel, the Rabbis assert that he advised Balak, as a last resort, to tempt the Hebrew nation to immoral acts and, through these, to the worship of Baal-peor.

[18] Na'aman argued that the existing narrative in the collective Hebrew memory of Egyptian rule "was remodeled according to the realities of the late eighth and seventh centuries in Canaan, integrating the experience with the Assyrian oppression and deportations.

[19][20] The narrative of Numbers 31 specifically is one out of many in the Hebrew Bible seeking to establish the Israelites as the chosen people of the god Yahweh, who blessed them with victory in battle, health and prosperity, as long as they were faithful to his commands.

[4] Both Olson and Brown noted that Moses is portrayed as remarkably passive in chapter 25 and, as he was failing to solve the problem, Phinehas had to intervene and take the initiative to slay Kozbi and Zimri, was granted the eternal priesthood and later allowed to lead the Israelites against Midian.

Evidently, something that the Israelite man Zimri and especially the Midianite princess Kozbi did was at the root of the conflict, though what offence they allegedly committed is a source of scholarly confusion.

"[2]: 155 He also pointed to Psalm 106:28–31,[2]: 155 which claims that the plague broke out due to Yahweh being angry at the Israelites for "eating sacrifices offered to lifeless gods" at Peor.

[32] Finally, Olson argued that Moses' apparent failure to punish the idolaters (25:4–5) is what motivated Phinehas to take matters into his own hands by killing Zimri and Kozbi.

[2]: 155 Brown (2015) stated: "In Num 31:16, Moses justifies his command by appealing to the Midianites' role in the apostasy and plague recounted in Numbers 25, and commentators have generally accepted that explanation and concluded that the text portrays the utter destruction of Midian as the fulfillment of YHWH's call for 'vengeance'.

[24] Victor P. Hamilton concluded in 2005 that Yahweh commanded holy war against Midian "in retaliation for the latter's seduction of Israel into acts of harlotry and idolatry".

[34] Sarah Shectman argued in 2009 that Zimri and Kozbi were not guilty of sexual transgressions at all; sex with a foreigner is never even considered a capital offence by the Holiness code (H).

[3] Unlike the non-P text in 25:1–5, there is no indication that there is anything particularly wrong with Kozbi as a woman or a foreigner, nor are she and Zimri accused of sexual transgression; they are both simply people from categories forbidden to encroach on the Tabernacle.

[3] Based on his exegesis of Joshua 24:9, Ellicott (1905) argued that Balaam's curse against Israel and the war in Numbers 31 were two separate acts of hostility initiated by Balak.

[31] Simultaneously, however, the Israelite soldiers are said to be defiled by the killing, and in need of a seven-day purification of their bodies, clothes and metal possessions, and to require "atonement for ourselves before Yahweh" (verse 50).

[31] Thus, the use of military violence, even if divinely mandated, is cast as a negative act that, in order to be erased, requires ritual cleansing of the body and possessions, as well as sacrifice in the form of 0.2% share of the soldiers' spoils as a tribute to Yahweh.

[31][1][3] Dennis T. Olson wrote in 2012 that "the bulk of the chapter deals with the purification of soldiers and booty from the impurity of war and the allotment of the spoils", while "the actual battle is summarized in two verses".

But understood within the symbolic world of the ancient writers of Numbers, the story of the war against the Midianites is a kind of dress rehearsal that builds confidence and hope in anticipation of the actual conquest of Canaan that lay ahead.

... Like Num 25, the story recounted in Judges 19–21 centers on the danger of apostasy, but its tale of civil war and escalating violence also emphasizes the tragedy that can result from the indiscriminate application of [vengeance].

"[4]: 77–78 Keith Allan in 2019 remarked: "God's work or not, this is military behaviour that would be tabooed today and might lead to a war crimes trial.

Rabbi and scholar Shaye J. D. Cohen (1999) argued that "the implications of Numbers 31:17–18 are unambiguous ... we may be sure that for yourselves means that the warriors may 'use' their virgin captives sexually", adding that Shimon bar Yochai understood the passage 'correctly'.

[45] In The Age of Reason (1795), Thomas Paine wrote about the chapter: "Among the detestable villains that in any period of the world would have disgraced the name of man, it is impossible to find a greater than Moses, if this account be true.

"[46][43] Richard Watson, the Bishop of Llandaff, sought to refute Paine's arguments:[43] I see nothing in this proceeding, but good policy, combined with mercy.

Debating Baptist minister Al Sharpton in 2007, atheist writer Christopher Hitchens argued that the Binding of Isaac and the extermination of the Amalekites were immoral divine commandments in the Old Testament, and recalled the previous debate: "The Bishop of Llandaff, in an argument with Thomas Paine, once said, 'Well, when it says keep the women,' as Paine had pointed out, he said, 'I'm sure God didn't mean just to keep them for immoral purposes.'

The "lucky" people, the virgin girls who are allowed to live, are made into sex slaves for disgusting, homicidal post hoc mercenaries that do all of their bidding from a man who says that a god that (no one can see) tells them to do.

After recounting the story of Jephthah's daughter in Judges 11, he reasoned: "the Jews (according to Numbers, chap 31) took 61,000 asses, 72,000 oxen, 675,000 sheep, and 32,000 virgins (whose fathers, mothers, brothers &c., were butchered).

[42]: 404 Although "[s]uch ritual activity is condemned by Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and other biblical writers (e.g., Lev 18:21, Deut 12:31, 18:10; Jer 7:30–31, 19:5; Ezek 20:31), and the seventh-century reformer king Josiah sought to put an end to it, [the] notion of a god who desires human sacrifice may well have been an important thread in Israelite belief.

"[42]: 404–405 She cited the Mesha Stele as evidence that the neighbouring Moabites performed human sacrifices with prisoners of war to their god Chemosh after successfully attacking an Israelite city in the 9th century BCE.

[42]: 405 Before the 7th-century BCE reformers of king Josiah of the southern Kingdom of Judah tried to end the practice of human/child sacrifice, it appears to have been commonplace in Israelite military culture.

[42]: 404 Carl Friedrich Keil and Franz Delitzsch argued in 1870 that the 32 were enslaved: Of the one half the priests received 675 head of small cattle, 72 oxen, 61 asses, and 32 maidens for Jehovah; and these Moses handed over to Eleazar, in all probability for the maintenance of the priests, in the same manner as the tithes (Numbers 18:26–28, and Leviticus 27:30–33), so that they might put the cattle into their own flocks (Numbers 35:3), and slay oxen or sheep as they required them, whilst they sold the asses, and made slaves of the gifts; and not in the character of a vow, in which case the clean animals would have had to be sacrificed, and the unclean animals, as well as the human beings, to be redeemed (Leviticus 27:2–13).