Herjolfsnes

As noted in the Landnámabók (Icelandic Book of Settlements), Herjolf Bardsson was one of the founding chieftains of the Norse colony in Greenland, and was said to be "a man of considerable stature.

Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad believed that the saga's author may have written the two men out of the story in order to elevate the exploits of Leif Eriksson, the first known European to land in North America.

One account tells of 12th century Icelanders who were shipwrecked on the east coast and perished while trying to cross the inland glaciers in an attempt to reach Herjolfsnes, only to be buried there instead.

For bodies lost or buried at sea, it appears to have been the custom to carve commemorative runes onto a stick which was then placed in the Herjolfsnes graveyard when the ship made landfall there.

The nearby Makkarneq Bay, which offers much better shelter than Herjolfsnes proper, features several Norse ruins that appear to include the foundations of stone warehouses, and is thus a possible site of the Sand harbour that Bardarson described.

The Little Climatic Optimum then under way would have made the southwest coast especially unsuited to the Dorset's arctic hunter-gatherer way of life; they are believed to have had great difficulty adapting to this warm period, and retreated progressively farther north.

It was only later that the Norse came into direct contact with related peoples in Greenland itself, the Thule culture, who supplanted the Dorset throughout the North American Arctic starting circa AD 1000.

These contacts likely started when the Norse began to make regular hunting trips far north of their settlements - or to the island's east coast - to obtain walrus and narwhal ivory.

With the advent of the Little Ice Age, Greenland's cooling climate prompted the Thule to increase their southern range, and brought them into greater contact with the Norse than had been the case with the Dorset.

Recent archaeological soil testing of Norse and Thule building ruins in Makkarneq Bay a few kilometres west of Herjolfsnes suggests that both peoples occupied the area at the same time.

There is no indication from archaeology or human remains that the Norse intermarried with the Thule or adopted their way of life, nor any record from Iceland or Norway that hints of an exodus out of Greenland.

These concerns were echoed in a letter dated circa 1500 by Pope Alexander VI, who believed that no communion had been performed in Greenland for a century, and that no ship had visited there in the past 80 years.

[12]Although there is no first-hand account of Norse Greenlanders living after 1410, analysis of the clothing buried at Herjolfsnes suggests that there was a remnant population who continued to have some sort of contact with the outside world for at least a few more decades.

[15] Helge Ingstad asserted that on balance, the graveyard's remains and artifacts indicate a relatively healthy and prosperous people who generally reflected the social and religious mores of Northern European Christendom.

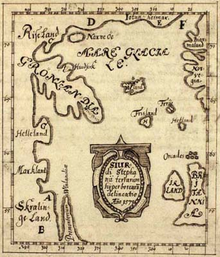

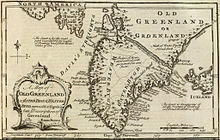

Egede held the then-common mistaken belief that major Eastern Settlement homesteads such as Herjolfsnes were to be found on Greenland's forbidding east coast.

[18] Throughout the remainder of his life, Egede was said to have fervently believed in the existence of a remnant population of Norse Greenlanders living in a yet-to-be-found Eastern Settlement, when in fact he had already thoroughly explored its ruins.

The formal re-discovery of the graveyard (by Europeans) was in the early 19th century when a missionary observed that a nearby Inuit house had a load-bearing doorway that was fashioned from an old tombstone bearing the name Hroar Kolgrimsson.

[21] The increasing number of wadmal fragments and garments being pulled from the ruins - and concern that the rising water line would soon submerge the site - prompted the Danish National Museum to launch an urgent formal excavation in 1921 led by Poul Nørlund.

Working under difficult conditions during the short digging season, Nørlund and his crew were eventually successful in recovering full and partial costumes, hats, hoods and stockings.

Careful analysis and reconstruction of the garments revealed the skill of the Herjolfsnes inhabitants at spinning and weaving, as well as their desire to follow European fashions such as the cotehardie, the liripipe hood and hats in the Burgunderhuen and Pillbox styles.

[22] The garments had been stained a dark brown from being buried, but testing revealed the presence of iron on some of them that appeared to have been deliberately and selectively introduced during manufacture rather than through ground contamination.

[23] In one sense, the quality, innovation and fashion awareness shown in the Herjolfsnes garments throw even more mystery on the disappearance of the settlement and the Norse colony.

In The Greenlanders, a 1988 historical fiction novel by Jane Smiley, Herjolfsnes is depicted as being set apart from the other districts in the Eastern Settlement owing to its location and its wealthy inhabitants, who wore distinct clothing and took pride in their greater knowledge of the outside world.