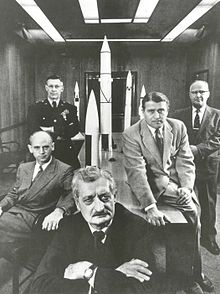

Hermann Oberth

[5] Oberth was born into a Transylvanian Saxon family in Nagyszeben (Hermannstadt), Kingdom of Hungary (today Sibiu in Romania);[6] and besides his native German, he was fluent in Hungarian and Romanian as well.

In 1912, Oberth began studying medicine in Munich, Germany, but after World War I broke out, he was drafted into the Imperial German Army, assigned to an infantry battalion, and sent to the Eastern Front against Russia.

In 1915, Oberth was moved into a medical unit at a hospital in Segesvár (German: Schäßburg; Romanian: Sighișoara), Transylvania, in Austria-Hungary (today Romania).

By 1917, he showed designs of a missile using liquid propellant with a range of 290 km (180 mi) to Hermann von Stein, the Prussian Minister of War.

However, professor Augustin Maior of the University of Cluj in Romania offered Oberth the opportunity to defend his original dissertation there in order to receive a doctorate.

[8] He next had his 92-page work published privately in June 1923 as the somewhat controversial book, Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen[11] (The Rocket into Planetary Space).

Oberth lacked the opportunities to work or to teach at the college or university level, as did many well-educated experts in the physical sciences and engineering in the time period of the 1920s through the 1930s – with the situation becoming much worse during the worldwide Great Depression that started in 1929.

Therefore, from 1924 through 1938, Oberth supported himself and his family by teaching physics and mathematics at the Stephan Ludwig Roth High School in Mediaș, Romania.

This honor recognized his significant contributions to the field of astronautics and interplanetary travel, specifically highlighted in his book Wege zur Raumschiffahrt[13] ("Ways to Spaceflight").

The book, an expanded version of Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen ("The Rocket to Interplanetary Space"), secured his position as a prominent figure in the field.

The engine was built by Klaus Riedel in a workshop space provided by the Reich Institution of Chemical Technology, and although it lacked a cooling system, it did run briefly.

Indeed, Von Braun said of him: Hermann Oberth was the first who, when thinking about the possibility of spaceships, grabbed a slide-rule and presented mathematically analyzed concepts and designs ...

On pages 350 to 386 in the chapter "Journeys to Strange Worlds", Hermann Oberth presents his scientific considerations and calculations for flights (including landings) to the Moon, to asteroids, to Mars, to Venus, to Mercury and to comets.

These mirrors, with diameters ranging from 100 to 300 km, were envisioned to be composed of a grid network consisting of individually adjustable facets.

This approach differs from creating shaded areas at the Lagrange point between the Earth and the Sun, as it does not involve diminishing solar radiation across the entire exposed surface.

According to Oberth, these colossal orbital mirrors possess the potential to illuminate individual cities, safeguard against natural disasters, manipulate weather patterns and climate, and even create additional living space for billions of people.

However, it is important to acknowledge that the implementation of such climate engineering interventions, including space mirrors, requires further extensive research before their practical applicability can be fully realized.

[11][13]: 87–88 [21][22][23] In 2023, the space mirror devised by Oberth is categorized within the field of Climate Engineering, specifically under Solar Radiation Management (SRM) as a subset of Space-Mirrors.

The tower-like structure has only one leg and it stands on a tracked chassis with a footprint of 2.5 m x 2.5 m. A motor with 51.5 kW of power is sufficient to drive at a speed of up to 150 km/h, depending on the terrain.

[26] Oberth writes: "I wanted to present my readers not just with a rough sketch of the lunar car, but with drawings and descriptions based on precise calculations and designs.

So I racked my brains over hundreds of details, calculated, compared, constructed, rejected and re-planned until the design was such that I could present it with a clear conscience.

From 1923 to 1938 Oberth worked with short breaks in 1929 and 1930 as a high school teacher for physics and mathematics in his home country Transylvania in Romania.

[19] The Romanian Hermann Oberth, known worldwide in the professional world, with his many foreign contacts, was regarded as a security risk for the secrecy of the development work on Aggregate 4 in Peenemünde.

[28] When he wanted to return to Transylvania in May 1941, he received German citizenship and was conscripted in August 1941 under the alias "Friedrich Hann"[29]: 58 to the Army Research Institute Peenemünde, where the world's first large rocket, the Aggregat 4 – later called "Vergeltungswaffe V2" – was developed under the direction of Wernher von Braun.

Oberth was not involved in this work,[29]: 58 [18]: 150 [28]: 157–164 [30]: 101 but placed in the patent review,[31]: 144 [18]: 94 and wrote various reports, for example "About the best outline of multi-stage rockets" and about "Defense against enemy planes with large, remote-controlled solid missile".

)[19] Around September 1943, he was awarded the Kriegsverdienstkreuz I Klasse mit Schwertern (War Merit Cross 1st Class, with Swords) for his "outstanding, courageous behavior ... during the attack" on 17./18.

In 1958, Oberth returned to Feucht, Germany, where he published his ideas for a lunar exploration vehicle, a "moon catapult", and "damped" helicopters and airplanes.

For example, in an article in The American Weekly magazine of 24 October 1954, Oberth stated: "It is my thesis that flying saucers are real, and that they are space ships from another solar system.

[34] The 1973 oil crisis inspired Oberth to look into alternative energy sources, including a plan for a wind power station that could utilize the jet stream.