Hermeneutic style

One, which he called the classical, was exemplified by the writings of Bede (c. 672–735), while the English bishop Aldhelm (c. 639–709) was the most influential author of the other school, which extensively used rare words, including Greek ones derived from "hermeneutic" glossaries.

In a 2005 study, J. N. Adams, Michael Lapidge and Tobias Reinhardt observe that "the exhumation of (poorly understood) Greek words from Greek-Latin glossaries for purposes of stylistic ornamentation was widespread throughout the Middle Ages.

[9][c]The hermeneutic style was possibly first seen in the Metamorphoses of Apuleius in the second century, and it is also found in works by late Latin writers such as Ammianus Marcellinus and Martianus Capella.

In Britain and Ireland, the style is found in authors on the threshold of the medieval period, including the British monk Gildas, the Irish missionary Columbanus and the Anglo-Saxon bishop Aldhelm, and works such as the Hisperica Famina.

[12] The Anglo-Saxons were the first people in Europe who had to learn Latin as a foreign language when they converted to Christianity, and in Lapidge's view: "That they attained stylistic mastery in a medium alien to them is remarkable in itself".

The other influential French author was Odo of Cluny, who was probably a mentor of Oda, Archbishop of Canterbury (941–958), a driving force behind the English Benedictine Reform and a proponent of the hermeneutic style.

His De Virginitate (On Virginity) was particularly influential, and in the 980s an English scholar requested permission from Archbishop Æthelgar to go to Winchester to study it, complaining that he had been starved of intellectual food.

[19] A passage in De Virginitate reads: Anglo-Latin suffered a severe decline in the ninth century, partly due to the Viking invasions, but it began to revive in the 890s under Alfred the Great, who revered Aldhelm.

One of them was a German, John the Old Saxon, and in Lapidge's view a poem he wrote praising the future King Æthelstan, and punning on the Old English meaning of Æthelstan as "noble stone", marks an early sign of a revival of the hermeneutic style: You, prince, are called by the name "sovereign stone", Look happily on this prophecy for your age: You shall be the "noble rock" of Samuel the Seer, [Standing] with mighty strength against devilish demons.

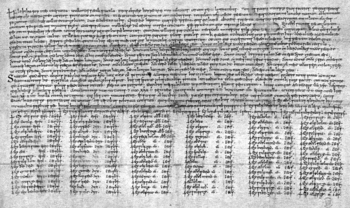

[25] According to Scott Thompson Smith, the charters of "Æthelstan A": "are generally characterised by a rich pleonastic style with aggressively literary proems and anathemas, ostentatious language and imagery throughout, decorative rhetorical figures, elaborate dating clauses and extensive witness lists.

[27] David Woodman gives a translation of the start of a charter drafted by "Æthelstan A", S 416 issued on 12 November 931: The lamentable and loudly detestable sins of this tottering age, surrounded by the dire barkings of obscene and fearsome mortality, challenge and urge us, not carefree in a homeland where peace has been attained but, as it were, teetering over an abyss of fetid corruption, that we should flee those things not only by despising them together with their misfortunes with the whole effort of our mind but also by hating them just like the wearisome nausea of melancholy, striving towards that Gospel text, "Give and it will be given unto you".

[31] Discussing the ideology of the reform movement, Caroline Brett comments: "The use of hermeneutic Latin with its deliberately obscure neologisms and verbal borrowings must have sent potent signals of a learned hierocratic caste, guardians of arcane yet powerful knowledge.

O omnipotent Father, may you deign to bring rewards to the donor – (you) who above the depths and realms of the heaven as well as the earth and at the same time the recesses of the sea – throughout all this world you rule the angelic citizens of such bounteous merit; and may you grant to grow in me the seed of holy labour by which I may always be able to hymn appropriately your name.

O you, Son, who, concealed in your mother's womb, you gather together peoples by your Father's act – for I perchance am able to compose a holy narrative because you are seen to be God, because, glorious one, the glittering stars show (you) to the world; and I ask, after the close of my life, that you grant to me from the throne of heaven to take a tiny gift because of the honour (I have) attained.

[e] Now I beseech the ancient fathers with Peter their leader on behalf of wretched and anxious me: pour out your prayers and aid so that the trinal custodian of each new saint may afterwards forgive me until I may overcome the hideous enemy of this world.

This presented Byrhtferth with a problem in his Enchiridion, a school text designed to teach the complicated rules for calculating the date of Easter, as hermeneutic Latin is unsuitable for pedagogic instruction.

Ealdorman Æthelweard was a descendant of King Æthelred I, grandfather of an Archbishop of Canterbury, and patron of Ælfric of Eynsham, the one major English writer of the period who rejected the style.

"[39] In 2005 Lapidge reflected: Thirty years ago, when I first attempted to describe the characteristic features of tenth-century Anglo-Latin literature, I was rather naively bedazzled by the display of vocabulary which one encounters there.

In his view: "however unpalatable this style might be to modern taste, it was none the less a vital and pervasive aspect of late Anglo-Saxon culture, and it deserves closer and more sympathetic attention than it has previously received".