Herxheim (archaeological site)

Styles of LBK pottery, some of a high quality, were discovered at the site from local populations as well as from distant lands from the north and east, even as far as 500 kilometres (310 mi) away.

[3] The structures at Herxheim suggested that of a large village spanning up to 6 hectares (15 acres) surrounded by a sequence of ovoid pits dug over a duration of several centuries.

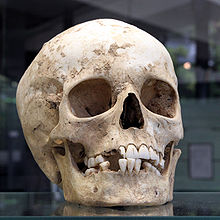

[1] Not only were cut marks found on locations of the skeleton that are made during the dismemberment and filleting process, bones were also crushed for the purposes of marrow extraction, and chewed.

"[1] Skeletal representation analysis revealed that many of the "spongy bone" elements - such as the spinal column, patella, ilium, and sternum - were underrepresented compared to what would be expected in a mass grave.

"[1] Additionally, preferential chewing of the metapodials and hand phalanges "speak strongly in favour of human choice rather than more or less random action by carnivores".

[1] The number of people concerned at Herxheim obviously suggests that cannibalism for the simple purpose of survival is highly improbable, all the more so as the characteristics of the deposits show a standard, repetitive, and strongly ritualised practice.

[1]A detailed study published by the excavators in 2015 estimates that the site contains the scattered remains of more than 1000 individuals, all of whom were butchered and eaten.

The other explanation is that the site was a major religious centre where human sacrifices (followed by cannibalism) took place and which was visited by people coming from various, sometimes faraway areas, some of whom were killed there.

[12] The original conclusion from the earlier 2006 study was that the site of Herxheim was a ritual mortuary center – a necropolis – for the LBK people of the area, where the remains of the dead were not just buried, but for reasons unknown, destroyed.

They considered the large number of corpses as well as the transportation of pottery and flint from distant areas to the site further arguments for this conjecture.

[3] The projection of the number of individuals present ... to a probable total of 1,300 to 1,500 rules out the possibility of a local graveyard — and points a regional centre at Herxheim to which human remains were transported for the purpose of reburial.... To organise the transport not only of stone tools and pottery but also of human bones and partial or maybe even complete corpses implies an efficient organisational and communication system.

This resulted in a controversy about which explanation was more plausible, with other archaeologists maintaining that the evidence better fits a scenario in which the dead were reburied following dismemberment and removal of flesh from bones.

"[13] However, in their later more detailed study the excavators point out that the human remains were put into the ditches quite shortly after their death (probably no more than a few days), when various body parts were still kept together by soft tissue.

[14] Moreover, the specific treatment of the bodies, such as the splitting of bones to extract the marrow, is typical for cannibalism and does not fit the observed patterns of secondary burials, and various other traces show that the corpses were processed in the same way as animals that are butchered, roasted and eaten.