Spinal column

Individual vertebrae are named according to their corresponding region including the neck, thorax, abdomen, pelvis or tail.

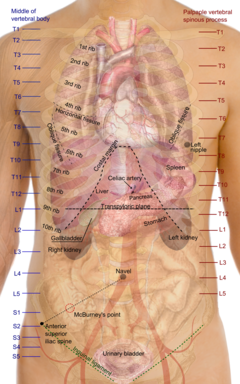

In clinical medicine, features on vertebrae such as the spinous process can be used as surface landmarks to guide medical procedures such as lumbar punctures and spinal anesthesia.

[3] The upper 24 pre-sacral vertebrae are articulating and separated from each other by intervertebral discs, and the lower nine are fused in adults, five in the sacrum and four in the coccyx, or tailbone.

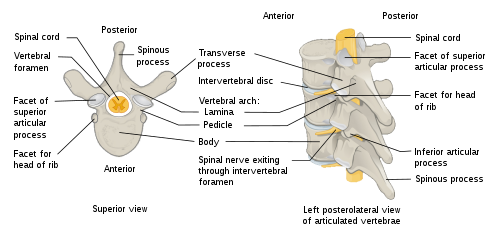

A typical vertebra consists of two parts: the vertebral body (or centrum), which is ventral (or anterior, in the standard anatomical position) and withstands axial structural load; and the vertebral arch (also known as neural arch), which is dorsal (or posterior) and provides articulations and anchorages for ribs and core skeletal muscles.

The transverse and spinous processes and their associated ligaments serve as important attachment sites for back and paraspinal muscles and the thoracolumbar fasciae.

The spinous processes of the cervical and lumbar regions can be felt through the skin, and are important surface landmarks in clinical medicine.

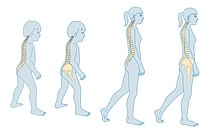

These curves increase the vertebral column's strength, flexibility, and ability to absorb shock, stabilising the body in upright position.

The lumbar curve is more marked in the female than in the male; it begins at the middle of the last thoracic vertebra, and ends at the sacrovertebral angle.

On either side of the spinous processes is the vertebral groove formed by the laminae in the cervical and lumbar regions, where it is shallow, and by the laminae and transverse processes in the thoracic region, where it is deep and broad; these grooves lodge the deep muscles of the back.

In the thoracic region, the sides of the bodies of the vertebrae are marked in the back by the facets for articulation with the heads of the ribs.

More posteriorly are the intervertebral foramina, formed by the juxtaposition of the vertebral notches, oval in shape, smallest in the cervical and upper part of the thoracic regions and gradually increasing in size to the last lumbar.

[14][better source needed] The supraspinous ligament extends the length of the spine running along the back of the spinous processes, from the sacrum to the seventh cervical vertebra.

The striking segmented pattern of the spine is established during embryogenesis when somites are rhythmically added to the posterior of the embryo.

The somites are spheres, formed from the paraxial mesoderm that lies at the sides of the neural tube and they contain the precursors of spinal bone, the vertebrae ribs and some of the skull, as well as muscle, ligaments and skin.

Somitogenesis and the subsequent distribution of somites is controlled by a clock and wavefront model acting in cells of the paraxial mesoderm.

Soon after their formation, sclerotomes, which give rise to some of the bone of the skull, the vertebrae and ribs, migrate, leaving the remainder of the somite now termed a dermamyotome behind.

The notochord disappears in the sclerotome (vertebral body) segments but persists in the region of the intervertebral discs as the nucleus pulposus.

[20] Excessive or abnormal spinal curvature is classed as a spinal disease or dorsopathy and includes the following abnormal curvatures: Individual vertebrae of the human vertebral column can be felt and used as surface anatomy, with reference points are taken from the middle of the vertebral body.

This provides anatomical landmarks that can be used to guide procedures such as a lumbar puncture and also as vertical reference points to describe the locations of other parts of human anatomy, such as the positions of organs.

The vertebral processes can either give the structure rigidity, help them articulate with ribs, or serve as muscle attachment points.

With the exception of the two sloth genera (Choloepus and Bradypus) and the manatee genus, (Trichechus),[24] all mammals have seven cervical vertebrae.

The synsacrum is a similar fused structure found in birds that is composed of the sacral, lumbar, and some of the thoracic and caudal vertebra, as well as the pelvic girdle.

A similar arrangement was found in the primitive Labyrinthodonts, but in the evolutionary line that led to reptiles (and hence, also to mammals and birds), the intercentrum became partially or wholly replaced by an enlarged pleurocentrum, which in turn became the bony vertebral body.

[26] In most ray-finned fishes, including all teleosts, these two structures are fused with, and embedded within, a solid piece of bone superficially resembling the vertebral body of mammals.

In living amphibians, there is simply a cylindrical piece of bone below the vertebral arch, with no trace of the separate elements present in the early tetrapods.

The upper tube is formed from the vertebral arches, but also includes additional cartilaginous structures filling in the gaps between the vertebrae, and so enclosing the spinal cord in an essentially continuous sheath.

[26] The general structure of human vertebrae is fairly typical of that found in other mammals, reptiles, and birds (amniotes).

Some unusual variations include the saddle-shaped sockets between the cervical vertebrae of birds and the presence of a narrow hollow canal running down the centre of the vertebral bodies of geckos and tuataras, containing a remnant of the notochord.

In living birds, the remaining caudal vertebrae are fused into a further bone, the pygostyle, for attachment of the tail feathers.

[26] The vertebral column in dinosaurs consists of the cervical (neck), dorsal (back), sacral (hips), and caudal (tail) vertebrae.