Tide

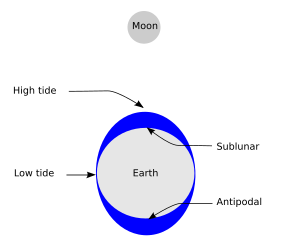

The solid Earth deforms a bit, but ocean water, being fluid, is free to move much more in response to the tidal force, particularly horizontally (see equilibrium tide).

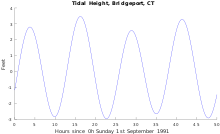

[13] Because the M2 tidal constituent dominates in most locations, the stage or phase of a tide, denoted by the time in hours after high water, is a useful concept.

Tidal motion generally lessens moving away from continental coasts, so that crossing the cotidal lines are contours of constant amplitude (half the distance between high and low water) which decrease to zero at the amphidromic point.

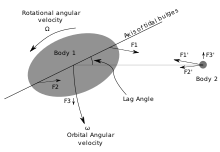

Investigation into tidal physics was important in the early development of celestial mechanics, with the existence of two daily tides being explained by the Moon's gravity.

[c] In De temporum ratione (The Reckoning of Time) of 725 Bede linked semidurnal tides and the phenomenon of varying tidal heights to the Moon and its phases.

His explanation of the tides (and many other phenomena) was published in the Principia (1687)[27][28] and used his theory of universal gravitation to explain the lunar and solar attractions as the origin of the tide-generating forces.

[e] Newton and others before Pierre-Simon Laplace worked the problem from the perspective of a static system (equilibrium theory), that provided an approximation that described the tides that would occur in a non-inertial ocean evenly covering the whole Earth.

[31] Pierre-Simon Laplace formulated a system of partial differential equations relating the ocean's horizontal flow to its surface height, the first major dynamic theory for water tides.

[37] From ancient times, tidal observation and discussion has increased in sophistication, first marking the daily recurrence, then tides' relationship to the Sun and moon.

In the 2nd century BC, the Hellenistic astronomer Seleucus of Seleucia correctly described the phenomenon of tides in order to support his heliocentric theory.

The first tide table in China was recorded in 1056 AD primarily for visitors wishing to see the famous tidal bore in the Qiantang River.

The first known British tide table is thought to be that of John Wallingford, who died Abbot of St. Albans in 1213, based on high water occurring 48 minutes later each day, and three hours earlier at the Thames mouth than upriver at London.

[44] In order to make these maps consistent, he hypothesized the existence of a region with no tidal rise or fall where co-tidal lines meet in the mid-ocean.

[45][46][32] Much later, in the late 20th century, geologists noticed tidal rhythmites, which document the occurrence of ancient tides in the geological record, notably in the Carboniferous.

The shape of the shoreline and the ocean floor changes the way that tides propagate, so there is no simple, general rule that predicts the time of high water from the Moon's position in the sky.

For example, the high tide at Norfolk, Virginia, U.S., predictably occurs approximately two and a half hours before the Moon passes directly overhead.

[62] The tidal forces due to the Moon and Sun generate very long waves which travel all around the ocean following the paths shown in co-tidal charts.

There are some extreme cases; the Bay of Fundy, on the east coast of Canada, is often stated to have the world's highest tides because of its shape, bathymetry, and its distance from the continental shelf edge.

Isaac Newton's theory of gravitation first enabled an explanation of why there were generally two tides a day, not one, and offered hope for a detailed understanding of tidal forces and behavior.

At each place of interest, the tide heights are therefore measured for a period of time sufficiently long (usually more than a year in the case of a new port not previously studied) to enable the response at each significant tide-generating frequency to be distinguished by analysis, and to extract the tidal constants for a sufficient number of the strongest known components of the astronomical tidal forces to enable practical tide prediction.

The tidal patterns are decomposed into many sinusoids having many fundamental frequencies, corresponding (as in the lunar theory) to many different combinations of the motions of the Earth, the Moon, and the angles that define the shape and location of their orbits.

Consider further that the tidal force on a location depends also on whether the Moon (or the Sun) is above or below the plane of the Equator, and that these attributes have their own periods also incommensurable with a day and a month, and it is clear that many combinations result.

Organisations quoting a "highest astronomical tide" for some location may exaggerate the figure as a safety factor against analytical uncertainties, distance from the nearest measurement point, changes since the last observation time, ground subsidence, etc., to avert liability should an engineering work be overtopped.

The lines rotate around the amphidromic points counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere so that from Baja California Peninsula to Alaska and from France to Ireland the M2 tide propagates northward.

The alternation in high tide heights becomes smaller, until they are the same (at the lunar equinox, the Moon is above the Equator), then redevelop but with the other polarity, waxing to a maximum difference and then waning again.

So far, there are few installed systems for tidal power generation (most famously, La Rance at Saint Malo, France) which face many difficulties.

Tidal heights are also important; for example many rivers and harbours have a shallow "bar" at the entrance which prevents boats with significant draft from entering at low tide.

The distance the tide moves the boat along this line is computed by the tidal speed, and this gives an "estimated position" or EP (traditionally marked with a dot in a triangle).

One easily visible feature is vertical zonation, in which the community divides into distinct horizontal bands of specific species at each elevation above low water.

Atmospheric tides are both gravitational and thermal in origin and are the dominant dynamics from about 80 to 120 kilometres (50 to 75 mi), above which the molecular density becomes too low to support fluid behavior.