Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel

The idea was introduced by David Hilbert in a 1925 lecture "Über das Unendliche", reprinted in (Hilbert 2013, p.730), and was popularized through George Gamow's 1947 book One Two Three...

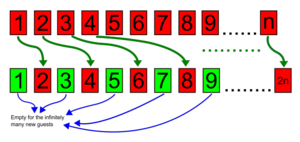

[1][2] Hilbert imagines a hypothetical hotel with rooms numbered 1, 2, 3, and so on with no upper limit.

This is called a countably infinite number of rooms.

A normal, finite hotel could not accommodate new guests once every room is full.

By repeating this procedure, it is possible to make room for any finite number of new guests.

Most methods depend on the seats in the coaches being already numbered (or use the axiom of countable choice).

In general any pairing function can be used to solve this problem.

For each of these methods, consider a passenger's seat number on a coach to be

This solution leaves certain rooms empty (which may or may not be useful to the hotel); specifically, all numbers that are not prime powers, such as 15 or 847, will no longer be occupied.

It is easier to show, by an independent means, that the number of arrivals is also greater than or equal to the number of vacancies, and thus that they are equal, than to modify the algorithm to an exact fit.)

, but whichever choice is made, it must be applied uniformly throughout.)

Like the prime powers method, this solution leaves certain rooms empty.

as written in any positional numeral system, such as decimal.

Unlike the prime powers solution, this one fills the hotel completely, and we can reconstruct a guest's original coach and seat by reversing the interleaving process.

First add a leading zero if the room has an odd number of digits.

Of course, the original encoding is arbitrary, and the roles of the two numbers can be reversed (seat-odd and coach-even), so long as it is applied consistently.

This pairing function can be demonstrated visually by structuring the hotel as a one-room-deep, infinitely tall pyramid.

The column formed by the set of rightmost rooms will correspond to the triangular numbers.

Once they are filled (by the hotel's redistributed occupants), the remaining empty rooms form the shape of a pyramid exactly identical to the original shape.

Doing this one at a time for each coach would require an infinite number of steps, but by using the prior formulas, a guest can determine what their room "will be" once their coach has been reached in the process, and can simply go there immediately.

This is a situation involving three "levels" of infinity, and it can be solved by extensions of any of the previous solutions.

The prime power solution can be applied with further exponentiation of prime numbers, resulting in very large room numbers even given small inputs.

For example, the passenger in the second seat of the third bus on the second ferry (address 2-3-2) would raise the 2nd odd prime (5) to 49, which is the result of the 3rd odd prime (7) being raised to the power of his seat number (2).

This room number would have over thirty decimal digits.

Thus, a guest with the prior address 2-5-1-3-1 (five infinite layers) would go to room 10010000010100010 (decimal 295458).

As an added step in this process, one zero can be removed from each section of the number; in this example, the guest's new room is 101000011001 (decimal 2585).

This ensures that every room could be filled by a hypothetical guest.

If no infinite sets of guests arrive, then only rooms that are a power of two will be occupied.

The paradox of Hilbert's Grand Hotel can be understood by using Cantor's theory of transfinite numbers.

For example, the set of rational numbers—those numbers which can be written as a quotient of integers—contains the natural numbers as a subset, but is no bigger than the set of natural numbers since the rationals are countable: there is a bijection from the naturals to the rationals.