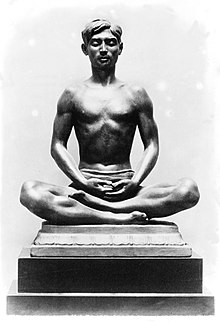

Dhyana in Hinduism

[7][8] It is, in Hinduism, a part of a self-directed awareness and unifying Yoga process by which the yogi realizes Self (Atman, soul), one's relationship with other living beings, and the Ultimate Reality.

[15] The root of the word is dhi, which, in the earliest layer of Vedic texts, refers to "imaginative vision" and is associated with goddess Saraswati, who possesses powers of knowledge, wisdom, and poetic eloquence.

[3][note 1] Dhyana, states Sagarmal Jain, has been essential to Jain religious practices, but the origins of Dhyana and Yoga in the pre-canonical era (before 6th-century BCE) is unclear, and it likely developed in the Sramanic culture of ancient India,[4] Several śramaṇa movements are known to have existed in India before the 6th century BCE (pre-Buddha, pre-Mahavira), and these influenced both the āstika and nāstika (i.e. Theistic and Atheistic) traditions of Indian philosophy.

[8] Alexander Wynne interprets Bronkhorst as stating that dhyana was a Jain tradition, from which both Hinduism and Buddhism borrowed ideas on meditation.

[33] Dhyana was incorporated into Buddhism from Brahmanical practices, suggests Wynne, in the Nikayas ascribed to Alara Kalama and Uddaka Rāmaputta.

[2] Techniques of concentration or meditation are a Vedic tradition, states Frits Staal, because these ideas are found in the early Upanishads as dhyana or abhidhyana.

[11][43][44] This interiorization of Vedic fire-ritual into yogic meditation ideas from Hinduism, that are mentioned in the Samhita and Aranyaka layers of the Vedas and more clearly in chapter 5 of the Chandogya Upanishad (~800 to 600 BCE),[note 4] are also found in later Buddhist texts and esoteric variations such as the Dighanikaya, Mahavairocana-sutra and the Jyotirmnjari, wherein the Buddhist texts describe meditation as "inner forms of fire oblation/sacrifice".

(...) The fire is meditation (dhyana), the firewood is truthfulness (satya), the offering is patience (kshanta), the Sruva spoon is modesty (hri), the sacrificial cake is not causing injury to living beings (ahimsa), and the priestly fee is the arduous gift of safety to all creatures.

[11] Adi Shankara dedicates an extensive chapter on meditation, in his commentary on the Brahma-sutras, in Sadhana as essential to spiritual practice.

[52] The verse 30.8 of the ancient Vasistha Dharma-sutra declares meditation as a virtue, and interiorized substitute equivalent of a fire sacrifice.

[55] Huston Smith summarizes the need and value of meditation in Gita, as follows (abridged): To change the analogy, the mind is like a lake, and stones that are dropped into it (or winds) raise waves.

Meditation in the Bhagavad Gita is a means to one's spiritual journey, requiring three moral values – Satya (truthfulness), Ahimsa (non-violence) and Aparigraha (non-covetousness).

[56] Dhyana in this ancient Hindu text, states Huston Smith, can be about whatever the person wants or finds spiritual, ranging from "the manifestation of divinity in a religious symbol in a human form", or an inspiration in nature such as "a snow-covered mountain, a serene lake in moonlight, or a colorful horizon at sunrise or sunset", or melodic sounds or syllables such as those that "are intoned as mantras and rhythmically repeated" like Om that is audibly or silent contemplated on.

[54][56] The Gita presents a synthesis[57][58] of the Brahmanical concept of Dharma[57][58][59] with bhakti,[60][59] the yogic ideals[58] of liberation[58] through jnana,[60] and Samkhya philosophy.

[web 2][note 5] It is the "locus classicus"[61] of the "Hindu synthesis"[61] which emerged around the beginning of the Common Era,[61] integrating Brahmanic and shramanic ideas with theistic devotion.

400 CE),[62] a key text of the Yoga school of Hindu philosophy, Dhyana is the seventh limb of this path, following Dharana and preceding Samadhi.

[67] Wynne, in contrast to Bronkhorst's theory, states that the evidence in early Buddhist texts, such as those found in Suttapitaka, suggest that these foundational ideas on formless meditation and element meditation were borrowed from pre-Buddha Brahamanical sources attested in early Upanishads and ultimately the cosmological theory found in the Nasadiya-sukta of the Rigveda.

[7] The Brahman has been variously defined in Hinduism, ranging from non-theistic non-dualistic Ultimate Reality or supreme soul, to theistic dualistic God.

[76] Vivekananda explains Dhyana in Patanjali's Yogasutras as, "When the mind has been trained to remain fixed on a certain internal or external location, there comes to it the power of flowing in an unbroken current, as it were, towards that point.

With practice, the process of Dhyana awakens self-awareness (soul, the purusha or Atman), the fundamental level of existence and Ultimate Reality in Hinduism, the non-afflicted, conflictless and blissful state of freedom and liberation (moksha).

[note 6]Michael Washburn states that the Yogasutras text identifies stepwise stages for meditative practice progress, and that "Patanjali distinguishes between Dharana which is effortful focusing of attention, Dhyana which is easy continuous one-pointedness, and Samadhi which is absorption, ecstasy, contemplation".

[80] With practice he is able to gain ease in which he learns how to contemplate in a sharply focussed fashion, and then "he is able more and more easily to give uninterrupted attention to the meditation object; that is to say, he attains Dhyana".

[91] The meditation technique discussed in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali is thus, states Mircea Eliade, a means to knowledge and siddhi (yogic power).

[90][92] Vācaspati Miśra, a scholar of the Vedanta school of Hinduism, in his bhasya on the Yogasutra's 3.30 wrote, "Whatever the yogin desires to know, he should perform samyama in respect to that object".

[93] Moksha (freedom, liberation) is one such practice, where the object of samyama is Sattva (pure existence), Atman (soul) and Purusha (Universal principle) or Bhagavan (God).

[94] Adi Shankara, another scholar of the Vedanta school of Hinduism, extensively commented on samyama as a means for Jnana-yoga (path of knowledge) to achieve the state of Jivanmukta (living liberation).

[102][103] The paths to be followed in order to attain enlightenment are remarkably uniform among all the Indian systems: each requires a foundation of moral purification leading eventually to similar meditation practices.

[2][109] This classification of four Dhyana types may have roots, suggests Paul Dundas, in the earlier Hindu texts related to Kashmir Shaivism.

[111][112] The 11th-century Vishishtadvaita Vedanta scholar Ramanuja noted that upasana and dhyana are equated in the Upanishads with other terms such as vedana (knowing) and smrti (remembrance).

According to Shankara, these texts discuss a personal deity and relate to ritual and upasana means devout contemplation on the conditioned Brahman.