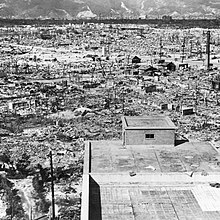

Hiroshima (book)

[1] The work was originally published in The New Yorker, which had planned to run it over four issues but instead dedicated the entire edition of August 31, 1946, to a single article.

[1][4] "Its story became a part of our ceaseless thinking about world wars and nuclear holocaust," New Yorker essayist Roger Angell wrote in 1995.

[9] Many radio stations abroad did likewise, including the BBC in Britain, where newsprint rationing that continued after the war's end prevented its publication; Hersey would not permit editing of the piece to cut its length.

"[3][6] Published a little more than a year after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, it showed the American public a different interpretation of the Japanese from what had been previously described in the media.

[11] After reading Hiroshima, a Manhattan Project scientist wrote that he wept as he remembered how he had celebrated the dropping of the atomic bomb.

[12] Hersey's work is often cited as one of the earliest examples of New Journalism in its melding of elements of non-fiction reportage with the pace and devices of the novel.

Hersey rarely gave interviews and abhorred going on anything resembling book tours, as his longtime editor Judith Jones recalled.

"If ever there was a subject calculated to make a writer overwrought and a piece overwritten, it was the bombing of Hiroshima", wrote Hendrik Hertzberg; "yet Hersey's reporting was so meticulous, his sentences and paragraphs were so clear, calm and restrained, that the horror of the story he had to tell came through all the more chillingly.

"[6] The founder of The New Yorker Harold Ross told his friend, author Irwin Shaw: "I don't think I've ever got as much satisfaction out of anything else in my life."

Despite Luce's misgivings about Hersey's choice of The New Yorker to print the Hiroshima story, the magazine's format and style allowed the author much more freedom in reporting and writing.

While editors Harold Ross and William Shawn spent long hours editing and deliberating every sentence, the magazine's staff was not told anything about the forthcoming issue.

[6] Time magazine said about Hiroshima: Every American who has permitted himself to make jokes about atom bombs, or who has come to regard them as just one sensational phenomenon that can now be accepted as part of civilization, like the airplane and the gasoline engine, or who has allowed himself to speculate as to what we might do with them if we were forced into another war, ought to read Mr. Hersey.

[15] While the majority of the excerpts praised the article, Mary McCarthy said that "to have done the atomic bomb justice, Mr. Hersey would have had to interview the dead".

[2][18] Although the US military government (headed by Douglas MacArthur)[19] dissuaded publishers from bringing out the book in Japan, small numbers of copies were distributed; in January 1947 Hersey gave a reading in English in Tokyo.

A noteworthy instance involved the denial in later 1946 of a request by the Nippon Times to publish John Hersey's Hiroshima (in English).

"[22] MacArthur said in 1948 that despite numerous charges of censorship made against the censor's office by the US news media, Hiroshima was not banned in Japan.

[24] The book begins with the following sentence: At exactly fifteen minutes past eight in the morning on August 6, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and was turning her head to speak to the girl at the next desk.Hersey introduces the six characters: two doctors, a Protestant minister, a widowed seamstress, a young female factory worker and a German Catholic priest.

A pastor at Hiroshima Methodist Church, a small man in stature, "quick to talk, laugh and cry", weak yet fiery, cautious and thoughtful, he was educated in theology in the U.S. at Emory University, in Atlanta, Georgia, speaks excellent English, obsessed with being spied on, Chairman of Neighborhood Association.

He is described as hedonistic, owner of a private 30-room hospital that contains modern equipment, has family living in Osaka and Kyushu, and is convivial and calm.

Weakened by his wartime diet, he feels unaccepted by the Japanese people and has a "thin face, with a prominent Adam's apple, a hollow chest, dangling hands, big feet.".

Miss Toshiko is at her desk and talking to a fellow employee at the Tin factory when the room filled with " a blinding light".

While reading his morning paper, Father Wilhem Kleinsorge witnesses a "terrible flash ... [like] a large meteor colliding with the earth".

Chapter three chronicles the days after the dropping of the bomb, the continuing troubles faced by the survivors, and the possible explanations for the massive devastation that the witnesses come across.

Once given the okay that the radiation levels in Hiroshima were acceptable and her appearance was presentable, she returned to her home to retrieve her sewing machine but it was rusted and ruined.

One year after the bombing, Mr. Tanimoto's church had been ruined and he no longer had his exceptional vitality; Mrs. Nakamura was destitute; Dr. Fujii had lost the thirty-room hospital it took him many years to acquire, and no prospects of rebuilding it; Father Kleinsorge was back in the hospital; Dr. Sasaki was not capable of the work he had once done; Miss Sasaki was a cripple.

In 1955, he returned to America with more Hiroshima Maidens, women who were school-age girls when they were seriously disfigured as a result of the bomb's thermal flash, and who went to the U.S. for reconstructive surgery.

She worked at a mothball factory for 13 years but did not immediately sign up for her health allowance through the A-bomb Victims Medical Care Law.

Sharp also saw Hiroshima as a counterpoint to "Yellow Peril" fiction like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, which were "narrated from the point of view of an 'everyman' who witnesses the invasion of his country first hand.

As the narrators struggle to survive, we get to witness the horror of the attack through their eyes, and come to loathe the enemy aliens that have so cruelly and unjustly invaded their country."

[32] Still, relevant anthologies like Nihon no Genbaku Bungaku or The Crazy Iris and Other Stories of the Atomic Aftermath are confined solely to Japanese writers.