Histone

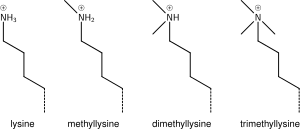

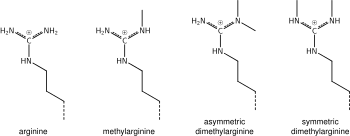

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei and in most Archaeal phyla.

For example, each human cell has about 1.8 meters of DNA if completely stretched out; however, when wound about histones, this length is reduced to about 9 micrometers (0.09 mm) of 30 nm diameter chromatin fibers.

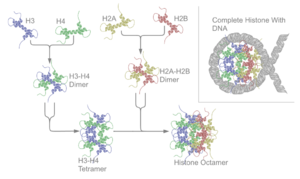

It is this helical structure that allows for interaction between distinct dimers, particularly in a head-tail fashion (also called the handshake motif).

[7] The resulting four distinct dimers then come together to form one octameric nucleosome core, approximately 63 Angstroms in diameter (a solenoid (DNA)-like particle).

In mammals, genes encoding canonical histones are typically clustered along chromosomes in 4 different highly-conserved loci, lack introns and use a stem loop structure at the 3' end instead of a polyA tail.

Genes encoding histone variants are usually not clustered, have introns and their mRNAs are regulated with polyA tails.

[10] Complex multicellular organisms typically have a higher number of histone variants providing a variety of different functions.

[12][13] Several pseudogenes have also been discovered and identified in very close sequences of their respective functional ortholog genes.

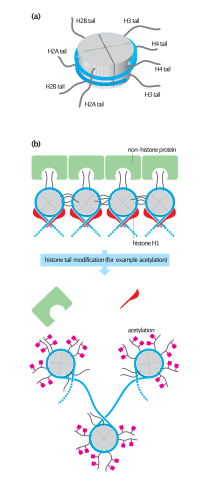

They also share the feature of long 'tails' on one end of the amino acid structure - this being the location of post-translational modification (see below).

Such dimeric structures can stack into a tall superhelix ("hypernucleosome") onto which DNA coils in a manner similar to nucleosome spools.

Histones are subject to post translational modification by enzymes primarily on their N-terminal tails, but also in their globular domains.

Core histones are found in the nuclei of eukaryotic cells and in most Archaeal phyla, but not in bacteria.

Histone H2A variant H2A.Z is associated with the promoters of actively transcribed genes and also involved in the prevention of the spread of silent heterochromatin.

Modifications of the tail include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, citrullination, and ADP-ribosylation.

[32][33] Histone modifications act in diverse biological processes such as gene regulation, DNA repair, chromosome condensation (mitosis) and spermatogenesis (meiosis).

[34] The common nomenclature of histone modifications is: So H3K4me1 denotes the monomethylation of the 4th residue (a lysine) from the start (i.e., the N-terminal) of the H3 protein.

However, most functional data concerns individual prominent histone modifications that are biochemically amenable to detailed study.

Recently it has been shown, that the addition of a serotonin group to the position 5 glutamine of H3, happens in serotonergic cells such as neurons.

[45] Addition of an acetyl group has a major chemical effect on lysine as it neutralises the positive charge.

Once the cell starts to differentiate, these bivalent promoters are resolved to either active or repressive states depending on the chosen lineage.

Without a repair marker, DNA would get destroyed by damage accumulated from sources such as the ultraviolet radiation of the sun.

Epigenetic modifications of histone tails in specific regions of the brain are of central importance in addictions.

[97][98][99] Once particular epigenetic alterations occur, they appear to be long lasting "molecular scars" that may account for the persistence of addictions.

In the nucleus accumbens of the brain, Delta FosB functions as a "sustained molecular switch" and "master control protein" in the development of an addiction.

In rats exposed to alcohol for up to 5 days, there was an increase in histone 3 lysine 9 acetylation in the pronociceptin promoter in the brain amygdala complex.

[121] For example, they found Histone IV sequence to be highly conserved between peas and calf thymus.

[120] Also in the 1960s, Vincent Allfrey and Alfred Mirsky had suggested, based on their analyses of histones, that acetylation and methylation of histones could provide a transcriptional control mechanism, but did not have available the kind of detailed analysis that later investigators were able to conduct to show how such regulation could be gene-specific.

[122] Until the early 1990s, histones were dismissed by most as inert packing material for eukaryotic nuclear DNA, a view based in part on the models of Mark Ptashne and others, who believed that transcription was activated by protein-DNA and protein-protein interactions on largely naked DNA templates, as is the case in bacteria.

During the 1980s, Yahli Lorch and Roger Kornberg[123] showed that a nucleosome on a core promoter prevents the initiation of transcription in vitro, and Michael Grunstein[124] demonstrated that histones repress transcription in vivo, leading to the idea of the nucleosome as a general gene repressor.

Vincent Allfrey and Alfred Mirsky had earlier proposed a role of histone modification in transcriptional activation,[125] regarded as a molecular manifestation of epigenetics.