Historiography of early Islam

[8][9] According to archaeologists Yehuda D. Nevo and Judith Koren, there are thousands of pagan and monotheist epigraphs or rock inscriptions throughout the Arabian peninsula and in the Syro-Jordanian desert immediately north, many of them dating from the 7th and 8th century.

Since validating the sayings of Muhammad is a major study ("Isnad"), accurate biography has always been of great interest to Muslim biographers, who accordingly attempted to sort out facts from accusations, bias from evidence, etc.

The classification of Hadith into Sahih (sound), Hasan (good) and Da'if (weak) was firmly established by Ali ibn al-Madini (778CE/161AH – 849CE/234AH).

A. Ahmad writes:[19] "The vagueness of ancient historians about their sources stands in stark contrast to the insistence that scholars such as Bukhari and Muslim manifested in knowing every member in a chain of transmission and examining their reliability.

The first detailed studies on the subject of historiography itself and the first critiques on historical methods appeared in the works of the Arab Muslim historian and historiographer Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), who is regarded as the father of historiography, cultural history,[20] and the philosophy of history, especially for his historiographical writings in the Muqaddimah (Latinized as Prolegomena) and Kitab al-Ibar (Book of Advice).

[21] His Muqaddimah also laid the groundwork for the observation of the role of state, communication, propaganda and systematic bias in history,[22][incomplete short citation] and he discussed the rise and fall of civilizations.

They translated the readily available Sunni texts from Arabic into European languages (including German, Italian, French, and English), then summarized and commented in a fashion that was often hostile to Islam.

Geiger's themes continued in Rabbi Abraham I. Katsh's "Judaism and the Koran" (1962)[29] Other scholars, notably those in the German tradition, took a more neutral view.

They tried to correct or reconstruct the early history of Islam from other, presumably more reliable, sources—such as found coins, inscriptions, and non-Islamic sources of that era.

[35] Nonetheless, his scepticism influenced a number of younger scholars, including: In 1977 Crone and Cook published Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World, which argued that the traditional early history of Islam is a myth, generated after the Arab conquests of Egypt, Syria, and Persia to give a solid ideological foundation to the new Arab regimes in those lands.

Crone defended the use of non-Muslim sources saying that "of course these sources are hostile [to the conquering Muslims] and from a classical Islamic view they have simply got everything wrong; but unless we are willing to entertain the notion of an all-pervading literary conspiracy between the non-Muslim peoples of the Middle East, the crucial point remains that they have got things wrong on very much the same points.

"[33] Crone and Cook's more recent work has involved intense scrutiny of early Islamic sources, but not their total rejection.

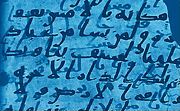

Puin has not published the entirety of his work, but has noted unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography.

In their study of the traditional Islamic accounts of the early conquest of different cities—Damascus and Caesarea in Syria, Babilyn/al-Fusat and Alexandria in Egypt, Tustar in Khuzistan and Cordoba in Spain—scholars Albrecht Noth and Lawrence Conrad find a suspicious pattern whereby the cities "are all described as having fallen into the hands of the Muslims in precisely the same fashion".

Notable scholars include: An alternative postrevisionist approach has made use of hadith of uncertain authenticity to tell a history of early Islam after the death of Muhammad.

Here the key has been to analyze hadith as collective memories that shaped the culture and society of urban Muslims in the late seventh and eighth centuries CE.