Historiography of the Suffragettes

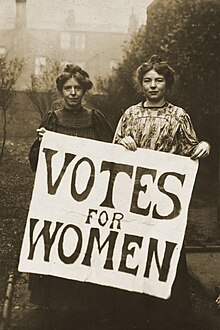

[2][3][4] Suffragettes, under the motto of “Deeds, Not Words”, engaged in civil disobedience and disruption, smashing windows, exploding letterboxes, cutting telegraph wires and storming parliament in an attempt to oversee the success of their cause.

The debate primarily centres around whether militancy was a justified, effective and decisive means to a failing political end, or acted as a hindrance to the ongoing constitutional campaigning of other suffragists by alienating politicians and the British public.

[5] The WSPU disputed this; Emmeline Pankhurst's ‘Freedom or Death’ speech of 1913 revealed her view that constitutional methods had been ineffective in gaining enfranchisement in a male-centred and male-dominated political environment.

Suffragette Annie Kenney said that at the time of the militant split, there was “no living interest in the question” of votes for women amongst the British public, rendering the campaign stagnant.

[5] Within The Cause, Strachey presents Suffragettes as inferior to constitutional suffragists through a dichotomous distinction between the “organised, powerful and politically important” NUWSS, compared to the “defiant and antagonistic” WSPU.

[13] She writes that militants displayed a “lack of dignity” and held “extraordinary notoriety”, which was directly rousing public protests and had “no favourable effect” on the campaign by antagonising the government.

[16] Indeed, Winston Churchill wrote in a letter to Christabel Pankhurst, cited within constitutionalist accounts, that his attitude of “growing sympathy” towards female enfranchisement was undermined by the actions of Suffragettes, who had alienated his support with their militant campaigning.

[5] The Masculinist school's analysis of Suffragettes focuses on blaming them for the failure of successive liberal governments to grant women the vote, due to their militant activities.

[18] Walter L. Arnstein similarly attributed Suffragettes as hindrances to their own efforts, writing “the law-minded prime minister” David Lloyd George was, “understandably enough, not attracted to a cause whose adherents vilified him” through militant attacks.

[18] However, defining the Masculinist school is also the view that women would have been granted this right eventually as the “vehicles of the inevitable historical processes that were the political actions of men”.

In terms of Suffragette history, this gave rise to the argument that militancy was necessary and effective not just as a political tactic, but as a significant symbol of wider female emancipation and societal change.

[24][23] She depicts militancy as justified within its context, as a tactic previously adopted by male suffragists, and analyses it as a mark of wider female emancipation, subverting traditional activities of women in the political sphere.