History of Atlanta

From the mid-1960s to mid-'1970s, nine suburban malls opened, and the downtown shopping district declined, but just north of it, gleaming office towers and hotels rose, and in 1976, the new Georgia World Congress Center signaled Atlanta's rise as a major convention city.

[8] In 1830, an inn was established that became known as Whitehall due to the then-unusual fact that it had a coat of white paint, when most other buildings were of washed or natural wood.

[citation needed] In 1836, the Georgia General Assembly voted to build the Western and Atlantic Railroad to provide a link between the port of Savannah and the Midwest.

[9] The initial route of that state-sponsored project was to run from Chattanooga, Tennessee, to a spot east of the Chattahoochee River, in present-day Fulton County.

He surveyed various possible routes, then in the autumn of 1837, drove a stake into the ground between what are now Forsyth Street and Andrew Young International Boulevard, about three or four blocks northwest of today's Five Points.

By 1855, the town had grown to 6,025 residents[23]: 86 and had a bank, a daily newspaper, a factory to build freight cars, a new brick depot, property taxes, a gasworks, gas street lights, a theater, a medical college, and juvenile delinquency.

Richard Peters, Lemuel Grant, and John Mims built a three-story flour mill, which was used as a pistol factory during the Civil War.

High rents rather than laws led to de facto segregation, with most black people settling in three shantytown areas at the city's edge.

With just 50 cents in their collective purse[citation needed], the sisters opened the Atlanta Hospital, the first medical facility in the city after the Civil War.

[citation needed] Nonetheless, African Americans in Atlanta had been developing their own businesses, institutions, churches, and a strong, educated middle class.

President Grover Cleveland presided over the opening of the exposition, but the event is best remembered for the both hailed and criticized "Atlanta Compromise" speech given by Booker T. Washington in which Southern black people would work meekly and submit to white political rule, while Southern whites guaranteed that black people would receive basic education and due process in law.

"Sweet" Auburn Avenue became home to Alonzo Herndon's Atlanta Mutual, the city's first black-owned life insurance company, and to a celebrated concentration of black businesses, newspapers, churches, and nightclubs.

In 1956, Fortune magazine called Sweet Auburn "the richest Negro street in the world", a phrase originally coined by civil-rights leader John Wesley Dobbs.

Noticeably absent was Hattie McDaniel, who won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role as Mammy, as well as Butterfly McQueen (Prissy).

Federal court decisions in 1962 and 1963 ended the county-unit system, thus greatly reducing rural Georgia control over the state legislature, enabling Atlanta and other cities to gain proportional political power.

[57] In the late 1950s, after forced-housing patterns[clarification needed] were outlawed, violence, intimidation, and organized political pressure were used in some white neighborhoods to discourage black people from buying homes there.

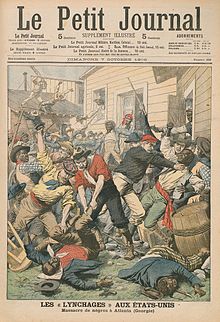

[61] In the wake of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, which helped usher in the Civil Rights Movement, racial tensions in Atlanta erupted in acts of violence.

The temple's leader, Rabbi Jacob Rothschild, actively spoke out in support of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement and against segregation, which is likely why the congregation was targeted.

In the 1960s, slums such as Buttermilk Bottom near today's Civic Center were razed, in principle to build better housing, but much of the land remained empty until the 1980s, when mixed-income communities were built in what was renamed Bedford Pine.

[citation needed] On the north side of Five Points, Downtown continued as the largest concentration of office space in Metro Atlanta, though it began to compete with Midtown, Buckhead, and the suburbs.

[77] African Americans became a majority in the city by 1970, and exercised new-found political influence by electing Atlanta's first black mayor, Maynard Jackson, in 1973.

[81][82] In 1993-1996 about 250,000 people attended Freaknik, an annual Spring Break gathering for African Americans which was not centrally organized and which resulted in much traffic gridlock and increased crime.

Following the announcement, Atlanta undertook several major construction projects to improve the city's parks, sports facilities, and transportation, including the completion of long-contested Freedom Parkway.

Prior to Franklin's term, Atlanta's combined sewer system violated the federal Clean Water Act and burdened the city government with fines from the Environmental Protection Agency.

In 2002, Franklin announced an initiative called "Clean Water Atlanta" to address the problem and begin improving the city's sewer system.

However, two holes were torn into the roof of the Georgia Dome, tearing down catwalks and the scoreboard as debris rained onto the court in the middle of an SEC game.

Much of the city's change during the decade was driven by young, college-educated professionals: from 2000 to 2009, the three-mile radius surrounding Downtown Atlanta gained 9,722 residents aged 25 to 34 holding at least a four-year degree, an increase of 61%.

Other areas, like Marietta and Alpharetta, are seeing similar demographic changes, with huge increases of middle and upper income black people and Asian people—mostly former residents of Atlanta.

[94] In 2009, the Atlanta Public Schools cheating scandal began, which ABC News called the "worst in the country",[95] resulting in the 2013 indictment of superintendent Beverly Hall.

[citation needed] In late May 2020 following George Floyd's murder, protests that developed into riots and looting occurred across Atlanta; mainly in the Downtown and Buckhead neighborhoods.