History of Central Africa

It is the ecoclimatic and biogeographic zone of transition in Africa between the Sahara desert to the north and the Sudanian Savanna to the south.

In 15,000 BP, the West African Monsoon transformed the landscape of Africa and began the Green Sahara period; greater rainfall during the summer season resulted in the growth of humid conditions (e.g., lakes, wetlands) and the savanna (e.g., grassland, shrubland) in North Africa.

[3] Between 25,000 BP and 20,000 BP, hunter-fisher-gatherer peoples in Central Africa (e.g., Ishango, Democratic Republic of Congo) utilized fishing tools and natural resources from nearby water sources, as well as may have engaged in and recorded mathematics (e.g., Ishango bone, which may demonstrate knowledge and use of the duodecimal system, prime numbers, multiplication).

[8] Rock art in Central Africa is generally located between the savanna and the Congo basin forest.

[9] There is rock art found in Cameroon (e.g., Bidzar; Galdi, Adamaoua; Djebel Mela, in Kotto and Lengo; Mbomou, Bangassou in Bakouma), the Democratic Republic of Congo (e.g., Bas-Congo; Ngembo; Fwakumbi), in Angola (e.g., Mbanza Kongo; Calola; Capelo; Bambala Rock Formations in the Upper Zambezi Valley), and in Gabon (e.g., Ogooue, Otoumbi; Oogoue, Kaya Kaya; Lope National Park).

[9] There are also some realistic animal depictions of lizards, six-legged lizards that appear commonly in African symbolisms, and a dotted hoe layered atop a throwing knife (the most common depiction on rock art in Central Africa) that indicates there were two distinct timeframes that engraving has occurred.

[15] In the 8th century CE, Wahb ibn Munabbih used Zaghawa to describe the Teda-Tubu group, in the earliest use of the ethnic name.

During the 1st millennium CE, as the Sahara underwent desiccation, people speaking the Kanembu language migrated to Kanem in the south.

Finally, around 1387 CE, the Bulala forced Mai Umar b. Idris to abandon Njimi and move the Kanembu people to Bornu on the western edge of Lake Chad.

He built a fortified capital at Ngazargamu, to the west of Lake Chad (in present-day Nigeria), the first permanent home a Sayfawa mai had enjoyed in a century.

Facing defeat, Nyikang left his homeland with his retinue and migrated northeast to Wau (near the Bahr el Ghazal, "river of gazelles" in Arabic).

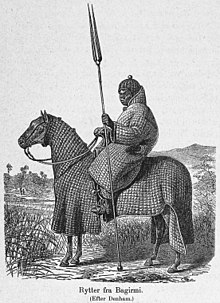

[31] The Bagirmi carried a tradition that they migrated from far to the east,[32] which is supported by the resemblance of their language to various tribes on the White Nile.

[34] The fourth king, Abdullah (1568 CE – 1608 CE), adopted Islam and converted the state into a sultanate, permitting the state to extend their authority over many pagan tribes in the area,[32] including the area's Saras, Gaberi, Somrai, Gulla, Nduka, Nuba, and Sokoro.

Over the centuries, the people of the region learned to use nets, harpoons, make dugout canoes, and clear canals through swamps.

[36] By the 6th century CE, fishing people lived on lakeshores, worked iron, and traded palm oil.

Traders exported salt and iron items, and imported glass beads and cowry shells from the distant Indian Ocean.

The Kingdom of Mbundu in the south and the BaKongo in the north were always at odds, but Kongo managed to exact tribute from these states since before the colonization by the Portuguese.

In the early 17th century CE, the Anziku population controlled the copper mines around Kongo's northeast border and may have been there specifically as a buffer.

There is no further information on the kingdom's early history and modern oral traditions do not seem to illuminate this at the present state of research.

Matamba undoubtedly had closer relations with its south southeastern neighbor Ndongo, then a powerful kingdom as well as with Kongo.

[40] The Yeke Kingdom (also called the Garanganze or Garenganze kingdom) of the Garanganze people in Katanga, DR Congo, was short-lived, existing from about 1856 CE to 1891 CE under one king, Msiri, but it became for a while the most powerful state in south-central Africa, controlling a territory of about half a million square kilometres.

It achieved this control through natural resources and force of arms—Msiri traded Katanga's copper principally, but also slaves and ivory, for gunpowder and firearms—and by alliances through marriage.

[47][48] At Ngongo Mbata, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, an individual, dated to the protohistoric period (220 BP), carried haplogroup L1c3a.

[47][48] At Matangai Turu Northwest, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, an individual, dated to the Iron Age (750 BP), carried an undetermined haplogroup(s).

[51] L1c prevalence was variously reported as: 100% in Ba-Kola, 97% in Aka (Ba-Benzélé), and 77% in Biaka,[52] 100% of the Bedzan (Tikar), 97% and 100% in the Baka people of Gabon and Cameroon, respectively,[53] 97% in Bakoya (97%), and 82% in Ba-Bongo.

[55][56] Evidence suggests that, when compared to other Sub-Saharan African populations, African pygmy populations display unusually low levels of expression of the genes encoding for human growth hormone and its receptor associated with low serum levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 and short stature.

[59] In the rainforests of Central Africa, genetic adaptation for non-height-related factors (e.g., immune traits, reproduction, thyroid function) and short stature (e.g., EHB1 and PRDM5 – bone synthesis; OBSCN and COX10 – muscular development; HESX1 and ASB14 – pituitary gland's growth hormone production/secretion) has been found among rainforest hunter-gatherers.

Dark Green: Central Africa (Geographic)

Medium Green: Middle Africa (UN Subregion)

Light Green/Gray: Central African Federation (Political: Defunct)