History of Chechnya

[3] The trend of a highly progressive Caucasus continued: as early as 3000–4000 BCE, evidence of metalworking (including copper[3]) as well as more advanced weaponry (daggers, arrow heads found, as well as armor, knives, etc.).

The Nakh on the northern side of the Greater Caucasus mountains, ancestors of the Chechens and Ingush, saw some southern tribes adopt Christianity due to Georgian influence in the fifth and sixth centuries, but they remained separate from Georgia.

Excavations have shown the presence of coins and other currency from Mesopotamia in the Middle East,[32] including an eagle cast in Iraq (found in Ingushetia) and buried treasure containing 200 Arabian silver dirhams from the 9th century in northern Chechnya.

[36] One particular tale recounts how the former inhabitants of Argun and the surrounding area held a successful defense (waged by men, women, and children) of the slopes of Mount Tebulosmta during the First Mongol Invasion, before returning to reconquer their home region.

Under the conditions of the invasion, Christianity (already originally highly dependent on connections with Georgia) was unable to sustain itself in Durdzuketia, and as its sanctuaries and priests fell, those who had converted reverted to paganism for spiritual needs.

The contribution of men, women, and children of all classes, paired with the destruction of the feudal system during the war, rich and poor, also helped the Vainakh develop a strong sense of egalitarianism, which was one of the major causes of the revolt against their new lords after the end of the Mongol invasions.

While the Chechens and Ingush primarily backed the anti-Tsarist forces in the Russian Revolution, because of this, and the threat to the Decossackization policies of the Bolsheviks, the Terek Cossacks almost universally filed into the ranks of Anton Denikin's anti-Soviet, highly nationalistic Volunteer Army.

Both hatred of the oppressor (Chechens generally failed to see the distinction between Russian and Cossack, and to this day they may be used as synonyms) and the need to either fill the mouths of hungry children and to regain lost lands played a role.

[44] In 1732, after Russia already ceded back most of the Caucasus to Persia, now led by Nader Shah, following the Treaty of Resht, Russian troops were ambushed by Chechen rebels near a village called Chechen–Aul along the Argun River.

While their program of united resistance to Russian conquest was popular, uniting Ichkeria/Mishketia with Dagestan was not necessarily (see Shamil's page), especially as some Chechens still practiced the indigenous religion, most Chechen Muslims belonged to heterodox Sufi Muslim teachings (divided between Qadiri and Naqshbandiya, with a strong Qadiri majority), rather than the more orthodox Sunni Islam of Dagestan; and finally, the rule of Ichkeria by a foreign ruler not only spurred distrust, but also threatened the existence of Ichkeria's indigenous "taip-conference" government structure.

Imam Shamil, among modern Chechens, is alternately glorified and demonized: his memory is evoked as someone who successfully held off Russian conquest, but on the other hand, he ruled Ichkeria heavy-handedly, and was an Avar who worked mainly for the interest of his own people.

All these revolts drew their force from the mass opposition of the population to the brutality and exploitation of Russian colonialist rule (even among peoples like Georgians, Azeris and Talysh who had originally been incorporated relatively easily), and used similar guerrilla tactics.

[65] By the end of the 19th century, major oil deposits were discovered around Grozny (1893) which along with the arrival of the railroad (early 1890s), brought economic prosperity to the region (then administered as part of the Terek Oblast) for the oil-mining Russian colonists.

The conflict with Russia and its final incorporation into the empire, however, brought about the formation of a modern, European, nationalist identity of Chechens, though it ironically solidified their separation, mainly over politics, from the Ingush.

At only one year into the conflict, five distinct forces with separate interests had formed with influence in Chechnya: the Terek Cossacks, the "Bourgeois" Chechens following Tapa Chermoev, the Qadiri Communist-Islamists under Ali Mitayev, the urban Russian Bolsheviks in Groznyi, and lastly, the relatively insignificant Naqshbandis with loyalties to Islamists in Dagestan.

Chermoev and the other major figures among the Mountain Republic sought to incorporate the Cossacks (establishing what would have been essentially the first friendly relations between Chechens and Cossacks- unsurprisingly, the uneasy alliance soon gave way).

But our fervent belief in justice and our faith in the support of the freedom-loving peoples of the Caucasus and of the entire world inspire me toward this deed, in your eyes impertinent and pointless, but in my conviction, the sole correct historical step.

Germany sent saboteurs and aided the rebels at times with Abwehr's Nordkaukasische Sonderkommando Schamil, which was sent on the premise of saving the oil refinery in Grozny from destruction by the Red Army (which it accomplished).

[85][86] Many times, resistance was met with slaughter, and in one such instance, in the aul of Khaibakh, about 700 people were locked in a barn and burned alive by NKVD general Gveshiani, who was praised for this and promised a medal by Lavrentiy Beria.

[88][89] Throughout the North Caucasus, about 700,000 (according to Dalkhat Ediev, 724,297,[90] of which the majority, 479,478, were Chechens, along with 96,327 Ingush, 104,146 Kalmyks, 39,407 Balkars and 71,869 Karachais), died along the trip, and the extremely harsh environment of Central Asia (especially considering the amount of exposure) killed many more.

[122][123] On August 27, 1958, Major General Stepanov of the Military Aviation School issued an ultimatum to the local Soviet government that the Chechens must be sent back to Siberia and Central Asia or otherwise his Russians would "tear (them) to pieces".

One of the most significant of these was on April 26, 1990, when the Supreme Soviet declared that the ASSRs within Russia get "the full plenitude of state power", and put them on the same levels as Union Republics, which had the (at least nominal) right to secession.

90,000 people (mainly Russians and Ukrainians) fled Chechnya during 1991–93 due to fears of, and possibly actual manifestation of ethnic tension (the situation was exacerbated by their lack of incorporation into the Chechen clan system, which protects its members to a degree from crime, as well).

[144] Dudayev was criticized by much of the Chechen political spectrum (particularly in urban Grozny) for his economic policies, a number of eccentric and embarrassing statements (such as insisting that "Nokhchi" meant descendant of Noah and that Russia was trying to destabilize the Caucasus with earthquakes), and his connections to former criminals (some of which, such as Beslan Gantemirov defected to the Russian side and served under Russian-backed regional governments[146]).

With the new troops also came new weaponry, and from this point forward, the tables were turned, with the Russian army becoming more and more mutinous and lacking of morale, while the anti-Russian side was growing stronger and more confident[154] (see also: First Chechen War, on this phenomenon).

Basayev, despite criticizing Yandarbiyev's policy towards radical Islamic groups, stated that attacks on Russian territory outside Chechnya should be executed if it is necessary to remind Russia that Ichkeria was not a pushover.

[167][168] Caving to intense pressure from his Islamist foes in his desire to find a national consensus, Maskhadov allowed the proclamation of the Islamic Republic of Ichkeria in 1998 and the Sharia system of justice was introduced.

President Maskhadov started a major campaign against hostage-takers, and on October 25, 1998, Shadid Bargishev, Chechnya's top anti-kidnapping official, was killed in a remote controlled car bombing.

Headed by Shamil Basayev and Amir Khattab (who were opposed vehemently by the government in Grozny, from which they had broken off allegiance), the insurgents fought Russian forces in Dagestan for a week before being driven back into Chechnya proper.

However, it was widely criticized, and in some cases, the vote recorded was not only vastly more than the actual population living there, but the majority of "voters" were Russian soldiers and dead Chechens (who of course were "loyal" pro-Russians, according to the results).

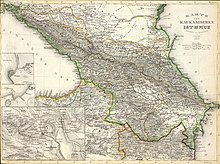

by J. Grassl, 1856.