History of Chinese Americans

[5] Only since the 1940s, when the United States and China became allies during World War II, did the situation for Chinese Americans begin to improve, as restrictions on entry into the country, naturalization, and mixed marriage were lessened.

Because it was usual at that time in China to live in confined social nets, families, unions, guilds, and sometimes whole village communities or even regions (for instance, Taishan) sent nearly all of their young men to California.

The Chinese immigrants neither spoke nor understood English and were not familiar with Western culture and life; they often came from rural China and therefore had difficulty in adjusting to and finding their way around large towns such as San Francisco.

Under Qing dynasty law, Han Chinese men were forced under the threat of beheading to follow Manchu customs including shaving the front of their heads and combing the remaining hair into a queue.

[34] Laws passed by the California state legislature in 1866 to curb the brothels worked alongside missionary activity by the Methodist and Presbyterian Churches to help reduce the number of Chinese prostitutes.

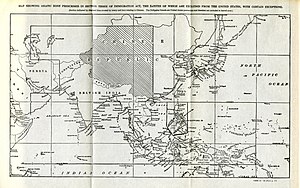

On March 3, 1875, in Washington, D.C., the United States Congress enacted the Page Act that forbade the entry of all Chinese women considered "obnoxious" by representatives of U.S. consulates at their origins of departure.

[4] Pre-1911 revolutionary Chinese society was distinctively collectivist and composed of close networks of extended families, unions, clan associations and guilds, where people had a duty to protect and help one another.

There were constant internecine battles over territory, profits, and women in feuds known as the tong wars, which began in the 1850s and lasted until the 1920s, notably in San Francisco, Cleveland, and Los Angeles.

The West Coast of North America was being rapidly settled by European Americans during the California Gold Rush, while southern China suffered from severe political and economic instability due to the weakness of the Qing government, along with massive devastation brought on by the Taiping Rebellion, which saw many Chinese emigrate to other countries to flee the fighting.

As a result, many Chinese made the decision to emigrate from the chaotic Taishanese- and Cantonese-speaking areas in Guangdong province to the United States to find work, with the added incentive of being able to aid their family back home.

At that time, "Chinese immigrants were stereotyped as degraded, exotic, dangerous, and perpetual foreigners who could not assimilate into civilized western culture, regardless of citizenship or duration of residency in the USA".

Construction began in 1863 at the terminal points of Omaha, Nebraska and Sacramento, California, and the two sections were merged and ceremonially completed on May 10, 1869, at the famous "golden spike" event at Promontory Summit, Utah.

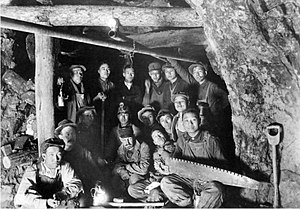

Even though at first they were thought to be too weak or fragile to do this type of work, after the first day in which Chinese were on the line, the decision was made to hire as many as could be found in California (where most were gold miners or in service industries such as laundries and kitchens).

[49] The route laid not only had to go across rivers and canyons, which had to be bridged, but also through the Sierra Nevada mountains — where long tunnels had to be bored through solid granite using only hand tools and black powder.

Many of these Chinese laborers were not unskilled seasonal workers, but were in fact experienced farmers, whose vital expertise the Californian fruit, vegetables and wine industries owe much to this very day.

Since the late 1850s, European migrants—above all Greeks, Italians, and Dalmatians—moved into fishing off the American West Coast too, and they exerted pressure on the California legislature, which, finally, expelled the Chinese fishermen with a whole array of taxes, laws and regulations.

The most disastrous effect occurred when the Scott Act, a federal U.S. law adopted in 1888, established that the Chinese migrants, even when they had entered and were living the United States legally, could not re-enter after having temporarily left U.S. territory.

In 1876, in response to the rising anti-Chinese hysteria, both major political parties included Chinese exclusion in their campaign platforms as a way to win votes by taking advantage of the nation's industrial crisis.

In July 1869, in the Southern United States, at an immigration convention at Memphis, a committee was formed to consolidate schemes for importing Chinese laborers into the South like the African Americans.

The vacant agricultural jobs subsequently proved to be so unattractive to the unemployed white Europeans that they avoided the work; most of the vacancies were then filled by Japanese workers, after whom in the decades later came Filipinos, and finally Mexicans.

Another anti-Chinese law was "An Act to Discourage Immigration to this State of Persons Who Cannot Become Citizens Thereof", which imposed on the master or owner of a ship a landing tax of fifty dollars for each passenger ineligible to naturalized citizenship.

In Lum v. Rice (1927), the Supreme Court affirmed that the separate-but-equal doctrine articulated in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), applied to a person of Chinese ancestry, born in and a citizen of the United States.

The court held that Miss Lum was not denied equal protection of the law because she was given the opportunity to attend a school which "receive[d] only children of the brown, yellow or black races".

[94] In his book published in 1890, How The Other Half Lives, Jacob Riis called the Chinese of New York "a constant and terrible menace to society",[95] "in no sense a desirable element of the population".

[99] In the late 19th century, many European Americans visited Chinatown to experience it via "slumming", wherein guided groups of affluent New Yorkers explored vast immigrant districts of New York such as the Lower East Side.

In 1868, one of the earliest Chinese residents in New York, Wah Kee, opened a fruit and vegetable store on Pell Street with rooms upstairs available for gambling and opium smoking.

[108] In late-19th century San Francisco, most notably Jackson Street, prostitutes were often housed in rooms 10×10 or 12×12 feet and were often beaten or tortured for not attracting enough business or refusing to work for any reason.

[123] Anti-Chinese advocates believed America faced a dual dilemma: opium smoking was ruining moral standards, and Chinese labor was lowering wages and taking jobs away from European Americans.

It was feared by these politicians (and no small amount of their constituents) that, if they were allowed to return home to the PRC, they would furnish America's newfound Cold War enemy with valuable scientific knowledge.

In addition to students and professionals, a recent third wave of immigrants, many of which entered the country without documentation (illegally), are people who travelled to the United States in search of lower-status manual labor jobs.