History of Christianity in Scotland

[1] The Christianity that developed in Ireland and Scotland differed from that led by Rome, particularly over the method of calculating Easter, and the form of tonsure until the Celtic church accepted Roman practices in the mid-seventh century.

The kirk would find it difficult to penetrate the Highlands and Islands, but began a gradual process of conversion and consolidation that, compared with reformations elsewhere, was conducted with relatively little persecution.

The late eighteenth century saw the beginnings of a fragmentation of the Church of Scotland that had been created in the Reformation around issues of government and patronage, but reflected a wider division between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party.

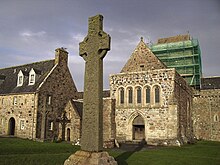

[17] Some early Scottish establishments had dynasties of abbots, who were often secular clergy with families, most famously at Dunkeld and Brechin; but these also existed across Scotland north of the Forth, as at Portmahomack, Mortlach, and Abernethy.

[18] Subsequent foundations under Edgar (r. 1097–1107), Alexander (r. 1107–24) and David I (r. 1124–53), tended from the religious orders that originated in France in the eleventh and twelfth centuries and followed the Cluniac Reforms.

When Bishop John died in 1147 David was able to appoint another Tironensian monk, Herbert abbot of Kelso, as his successor and submission to York continued to be withheld.

However, unlike Ireland which had been granted four Archbishoprics in the same century, Scotland received no Archbishop and the whole Ecclesia Scoticana, with individual Scottish bishoprics (except Whithorn/Galloway), became the "special daughter of the see of Rome".

This led to the placement of clients and relatives of the king in key positions, including James IV's illegitimate son Alexander, who was nominated as Archbishop of St. Andrews at the age of eleven, intensifying royal influence and also opening the Church to accusations of venality and nepotism.

[34] Traditional Protestant historiography tended to stress the corruption and unpopularity of the late medieval Scottish church, but more recent research has indicated the ways in which it met the spiritual needs of different social groups.

[26][35] Historians have discerned a decline of monasticism in this period, with many religious houses keeping smaller numbers of monks, and those remaining often abandoning communal living for a more individual and secular lifestyle.

[24][38] There were further attempts to differentiate Scottish liturgical practice from that in England, with a printing press established under royal patent in 1507 in order to replace the English Sarum Use for services.

[24] Heresy, in the form of Lollardry, began to reach Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early fifteenth century, but despite evidence of a number of burnings and some apparent support for its anti-sacramental elements, it probably remained a relatively small movement.

[39] During the sixteenth century, Scotland underwent a Protestant Reformation that created a predominately Calvinist national kirk, which was strongly Presbyterian in outlook, severely reducing the powers of bishops, although not abolishing them.

In the earlier part of the century, the teachings of first Martin Luther and then John Calvin began to influence Scotland, particularly through Scottish scholars who had visited continental and English universities and who had often trained in the Catholic priesthood.

Wishart's supporters, who included a number of Fife lairds, assassinated Beaton soon after and seized St. Andrews Castle, which they held for a year before they were defeated with the help of French forces.

The survivors, including chaplain John Knox, being condemned to be galley slaves, helping to create resentment of the French and martyrs for the Protestant cause.

[41] Limited toleration and the influence of exiled Scots and Protestants in other countries, led to the expansion of Protestantism, with a group of lairds declaring themselves Lords of the Congregation in 1557 and representing their interests politically.

The collapse of the French alliance and English intervention in 1560 meant that a relatively small, but highly influential, group of Protestants were in a position to impose reform on the Scottish church.

At this point the majority of the population was probably still Catholic in persuasion and the kirk would find it difficult to penetrate the Highlands and Islands, but began a gradual process of conversion and consolidation that, compared with reformations elsewhere, was conducted with relatively little persecution.

In 1618, he held a General Assembly and pushed through Five Articles, which included practices that had been retained in England, but largely abolished in Scotland, most controversially kneeling for the reception of communion.

At the beginning of his reign, Charles' revocation of alienated lands since 1542 helped secure the finances of the kirk, but it threatened the holdings of the nobility who had gained from the Reformation settlement.

[48] In 1635, without reference to a general assembly of the Parliament, the king authorised a book of canons that made him head of the Church, ordained an unpopular ritual and enforced the use of a new liturgy.

When the liturgy emerged in 1637 it was seen as an English-style Prayer Book, resulting in anger and widespread rioting, said to have been set off with the throwing of a stool by one Jenny Geddes during a service in St Giles Cathedral.

[61] In the early 1680s a more intense phase of persecution began, in what was later to be known in Protestant historiography as "the Killing Time", with dissenters summarily executed by the dragoons of James Graham, Laird of Claverhouse or sentenced to transportation or death by Sir George Mackenzie, the Lord Advocate.

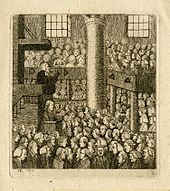

These fractures were prompted by issues of government and patronage, but reflected a wider division between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party over fears of fanaticism by the former and the acceptance of Enlightenment ideas by the latter.

[65] Long after the triumph of the Church of Scotland in the Lowlands, Highlanders and Islanders clung to an old-fashioned Christianity infused with animistic folk beliefs and practices.

[64] After prolonged years of struggle, in 1834 the Evangelicals gained control of the General Assembly and passed the Veto Act, which allowed congregations to reject unwanted "intrusive" presentations to livings by patrons.

Chalmers's ideals demonstrated that the church was concerned with the problems of urban society, and they represented a real attempt to overcome the social fragmentation that took place in industrial towns and cities.

[64] Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants, particularly after the famine years of the late 1840s, principally to the growing lowland centres like Glasgow, led to a transformation in the fortunes of Catholicism.

It is not subject to state control, and the monarch (currently King Charles III) is an ordinary member of the Church of Scotland, and is represented at the General Assembly by their Lord High Commissioner.