History of Galicia

When Spain transitioned to democracy following Franco's death in 1975, Galicia was allowed autonomy again, and there have been efforts since then to preserve Galician heritage and culture.

Peoples from the Castilian plateau moved to Galicia, thus increasing the population, because its position near the Atlantic Ocean gave it a very humid climate.

At the end of the Iron Age, people from northwestern Iberian Peninsula formed a homogeneous and distinct cultural group, which was later identified by early Greek and Latin authors, who called them "Gallaeci" (Galicians), perhaps due to their apparent similarity with the Galli (Gauls) and Gallati (Galatians).

The Gallaeci were originally a Celtic people who for centuries had occupied the territory of modern Galicia and northern Portugal; bounded to the south by the Lusitanians and to the east by the Astures.

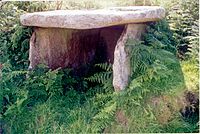

In the territory of actual Galicia alone, there exist more than two thousand hillforts, which shows the greatest dispersion of population from the Iron Age in Europe.

In religious terms, the Gallaeci showed a Celtic religion based on the cult to pan-Celtic gods as Bormanus, Coventina and Lugus; also Bandua, Cossus, Endovelicus, Reue, etc.

The knowledge that we have today about the society of the hillforts is very limited; according to the Roman historians, the Galicians were a collection of barbarians who spent the day fighting and the night eating, drinking and dancing to the moon.

The division of the country into concelhos, a concept similar to the counties of the islands[clarification needed] or Romania, seems to be based on this class of social organization.

When Iberia was involved in the Punic Wars between the Carthaginians and the Romans, the strategic alliance that they maintained with the Phoenicians enabled Hannibal to recruit many Gallegans.

At the end of Brutus' campaigns, Rome controlled the territory between the Douro and Minho rivers plus probable extensions along the coast and in the interior.

At Lorenzana, the fine sarcophagus that received at a later date the mortal remains of count Osorio Gutiérrez, was probably an import from southern Gaul in the 7th century, Fletcher notes.

The constant aggression and harassment that Jutes and Anglo-Saxons carried out against the native Britons caused some of them to emigrate by sea to other points near the Atlantic coast, settling in what is now northwest France Armorica (consequently, becoming known as Brittany) and in the north of the ancient Gallaecia.

[1] occupied mainly the coastal strip from the Lugo's coast to the Terra Chá, reaching his influence to the region of the Eo-Navia[1] from the east and the west of Ferrol.

Its ancient headquarters, known under the name Maximus Monastery was identified by some authors with the medieval Basilica of Saint Martin of Mondoñedo, were remnants of 5th–6th centuries.

Rodrigo, the last elected king, was betrayed by Julian, count of Ceuta, who called for the Umayyad Muslims (or Moors) to enter Hispania.

This rapid conquest can be understood as a continuation of the civil wars that had afflicted the peninsula for centuries, as well as through the conversion to Islam of a significant part of the population.

There is no evidence of any Moorish occupation of any settlement in modern Galicia and so it would be purely speculative to assume the region was ever conquered or even invaded by the Moors.

Notified by Pelagius, Theodemir, the bishop of Iria Flavia, travelled quickly to the place, identifying the remains found there as the decapitated body of the Apostle James.

Myth or reality, this "discovery" was quickly magnified by the Galician-Asturian monarch, Alphonse II (791–842), who in the same year ordered build a church around the tomb, spreading the news throughout Christendom.

From the 11th and 12th centuries especially, pilgrims from many parts of Europe began arriving, including from Occitania, France, Navarra and Aragon-Catalonia (by land) and from the British Isles, Scandinavia, and German territories (by sea).

Around the Apostolic tomb grew not only a cathedral – great center of artistic and religious life – but a village and then a town, strongly established in the Middle Ages, with a commercial derivative of its status as a holy city.

The city of Compostela would be where Galician kings were crowned, where the great Galician-Portuguese lyric school grew, and where the capital of Galicia has been located since the Middle Ages.

The Count of Portugal, Nuno Mendes, took advantage of the internal tension caused by the civil war between Ferdinand's sons to finally break off and declare himself an independent ruler.

An even later tradition states that he miraculously appeared to fight for the Christian army during the Battle of Clavijo during the Reconquista, and was henceforth called Matamoros (Moor-slayer).

Apparently due to unusually cold winters throughout the 1850s combined with the prevalence of subsistence agriculture, many Galician family farms went bankrupt.

From the second half of the 19th century onward Galicia's textile industry suffered a severe crisis brought on by the legal importation and the smuggling in of foreign fabrics, and many families endured hardship because there was no alternate source of employment.

As a result, emigration intensified...In December 1836 there appeared the first commercial advertisement offering transatlantic passage—aboard the [slave-ship] General Laborde—from A Coruña to Montevideo, Buenos Aires and other destinations in Mar del Plata.

The noted Galician writer and politician Alfonso Castelao (1886–1950)—himself an expatriate twice, during his childhood and after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936—chose to see in emigration both an economic imperative and the affirmation of a dauntless spirit.

[6] Galician nationalist and federalist movements arose in the 19th century, and after the Second Spanish Republic was declared in 1931, Galicia became an autonomous region following a referendum.

The only nationalist party of any electoral significance, the Bloque Nacionalista Galego or BNG, advocates greater autonomy from the Spanish state, and the preservation of Galician heritage and culture.