Don Quixote

[b] He recruits as his squire a simple farm labourer, Sancho Panza, who brings a unique, earthy wit to Don Quixote's lofty rhetoric.

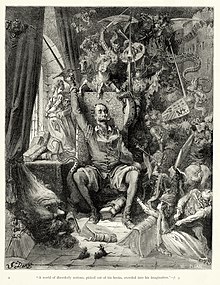

In the first part of the book, Don Quixote does not see the world for what it is and prefers to imagine that he is living out a knightly story meant for the annals of all time.

[8] The book had a major influence on the literary community, as evidenced by direct references in Alexandre Dumas's The Three Musketeers (1844),[9] and Edmond Rostand's Cyrano de Bergerac (1897)[10] as well as the word quixotic.

[14] Cervantes, in a metafictional narrative, writes that the first few chapters were taken from "the archives of La Mancha", and the rest were translated from an Arabic text by the Moorish historian Cide Hamete Benengeli.

Alonso Quixano is a hidalgo nearing 50 years of age who lives in a deliberately unspecified region of La Mancha with his niece and housekeeper.

Quixote takes the friars to be enchanters who are holding the lady captive, knocks one of them from his horse, and is challenged by an armed Basque travelling with the company.

After further adventures involving a dead body, a barber's basin that Quixote imagines as the legendary helmet of Mambrino, and a group of galley slaves, they wander into the Sierra Morena.

They make a plan to trick Quixote into coming home, recruiting Dorotea, a woman they discover in the forest, to pose as the Princess Micomicona, a damsel in distress.

This story, read to a group of travelers at an inn, tells of a Florentine nobleman, Anselmo, who becomes obsessed with testing his wife's fidelity and talks his close friend Lothario into attempting to seduce her, with disastrous results for all.

Following this example, Quixote would suggest 'The Great Quijano', an oxymoronic play on words that makes much sense in light of the character's delusions of grandeur.

[23] The traditional English rendering is preserved in the pronunciation of the adjectival form quixotic, i.e., /kwɪkˈsɒtɪk/,[24][25] defined by Merriam-Webster as the foolishly impractical pursuit of ideals, typically marked by rash and lofty romanticism.

[26] Harold Bloom says Don Quixote is the first modern novel, and that the protagonist is at war with Freud's reality principle, which accepts the necessity of dying.

[27] Edith Grossman, who wrote and published a highly acclaimed[28] English translation of the novel in 2003, says that the book is mostly meant to move people into emotion using a systematic change of course, on the verge of both tragedy and comedy at the same time.

The full title is indicative of the tale's object, as ingenioso (Spanish) means "quick with inventiveness",[30] marking the transition of modern literature from dramatic to thematic unity.

The novel takes place over a long period of time, including many adventures united by common themes of the nature of reality, reading, and dialogue in general.

Although burlesque on the surface, the novel, especially in its second half, has served as an important thematic source not only in literature but also in much of art and music, inspiring works by Pablo Picasso and Richard Strauss.

[citation needed] In exploring the individualism of his characters, Cervantes helped lead literary practice beyond the narrow convention of the chivalric romance.

Another prominent source, which Cervantes evidently admires more, is Tirant lo Blanch, which the priest describes in Chapter VI of Quixote as "the best book in the world."

They also found a person called Rodrigo Quijada, who bought the title of nobility of "hidalgo", and created diverse conflicts with the help of a squire.

(Somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember, a gentleman lived not long ago, one of those who has a lance and ancient shield on a shelf and keeps a skinny nag and a greyhound for racing.

[58] Spain's status as a world power was declining, and the Spanish national treasury was bankrupt due to expensive foreign wars.

[58] In 2002 the Norwegian Nobel Institute conducted a study among writers from 55 countries, the majority voted Don Quixote "the greatest work of fiction ever written".

[61] ("In a village of La Mancha, whose name I do not wish to recall, there lived, not very long ago, one of those gentlemen with a lance in the lance-rack, an ancient shield, a skinny old horse, and a fast greyhound.

[65] The phrase is sometimes used to describe either confrontations where adversaries are incorrectly perceived, or courses of action that are based on misinterpreted or misapplied heroic, romantic, or idealistic justifications.

[71] Although most of them disappeared in a shipwreck near La Havana, approximately 70 copies reached Lima, from where they were sent to Cuzco, in the heart of the defunct Inca Empire.

"[75] Don Quixote, Part Two, published by the same press as its predecessor, appeared late in 1615, and quickly reprinted in Brussels and Valencia (1616) and Lisbon (1617).

The translation, as literary critics claim, was not based on Cervantes' text but mostly on a French work by Filleau de Saint-Martin and on notes which Thomas Shelton had written.

[78] Nonetheless, future translators would find much to fault in Motteux's version: Samuel Putnam criticized "the prevailing slapstick quality of this work, especially where Sancho Panza is involved, the obtrusion of the obscene where it is found in the original, and the slurring of difficulties through omissions or expanding upon the text".

It leaves out the risqué sections as well as chapters that young readers might consider dull, and embellishes a great deal on Cervantes' original text.

[86] The fourth translation of the 21st century was released in 2006 by former university librarian James H. Montgomery, 26 years after he had begun it, in an attempt to "recreate the sense of the original as closely as possible, though not at the expense of Cervantes' literary style.