History of Liverpool

The history of Liverpool can be traced back to 1190 when the place was known as 'Liuerpul', possibly meaning a pool or creek with muddy water, though other origins of the name have been suggested.

The Calderstones are thought to be part of an ancient stone circle and there is archaeological evidence for native Iron Age farmsteads at several sites in Irby, Halewood and Lathom.

The area came under Roman influence in about 70 AD, with the northward advance to crush the druid resistance on Anglesey and to end the internal strife between the ruling family of Brigantes.

The thing-vollr in Norse meaning assembly field is found in Thingwall place names on both sides of the Mersey in West Derby and Wirral.

In 1086, the Domesday Book survey lists Roger de Poitou as the South Lancashire tenant-in-chief for Inter Ripam et Mersam lands between the Ribble and Mersey rivers, in the West Derby Hundred and, at the time, the northern part of Cheshire.

Other settlements are named in the West Derby Hundred including Bootle (Boltelai), Kirkdale (Circhdele), Walton (Waletone), Toxteth (Stochestede), Smithdown (Esmidune), Wavertree (Wauretreu), Childwall (Cildeuuelle), Allerton (Alretune), Little and Much Woolton (Uluentune), (Ulletone), Speke (Spec), Tarbock (Tarboc), Roby (Rabil), Huyton (Hitune), Knowsley (Chenulveslei), Kirkby (Cherchebi), Melling (Melinge), Maghull (Magele), Lydiate (Leidte), Sefton (Sextune), Thornton (Torentun), Litherland (Liderlant), Crosby (Crosebi), Formby (Fornebei), Ravenmeols (Mele), Little Altcar (Acrer), Ainsdale (Einulvesdel), North Meols (Otegrimele).

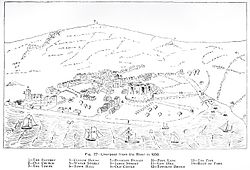

[8] Although a small motte and bailey castle had earlier been built at West Derby, the origins of the city of Liverpool are usually dated from 28 August 1207, when letters patent were issued by King John advertising the establishment of a new borough, "Livpul", and inviting settlers to come and take up holdings there.

With the formation of a market on the site of the later town hall, Liverpool became established as a small fishing and farming community administered by burgesses and, slightly later, a mayor.

By the end of the sixteenth century, the town began to be able to take advantage of economic revival and the silting of the River Dee to win trade, mainly from Chester, to Ireland, the Isle of Man and elsewhere.

[9] Liverpool merchants such as Foster Cunliffe and his apprentice William Bulkeley co-owned voyages for slaves, for Greenland whaling, and, especially during the Seven Years' War, privateering.

I have seen houses, with little low rooms, suffice for the dwelling of the merchant or well-to-do trader, the first being content to live in Water-St. or Oldhall-St., while the latter had no idea of leaving his little shop, with its bay or square window, to take care of itself at night...

The most enlightened of its inhabitants, at that time, could not boast of much intelligence, while [the] lower orders were plunged in the deepest vice, ignorance, and brutality... so barbarous were they in their amusements, bullbaiting and cock and dog fightings, and pugilistic encounters.

As a man, I have seen the old narrow streets widening – the old houses crumbling... and the sea influence recede before improvement, education and enlightenment of all sorts.

Between 1784 and 1790, when he stood down and was replaced by Banastre Tarleton, Penrhyn is reported to have made more than thirty speeches, all in vigorous defence of Liverpool trade or the West Indies.

Penrhyn spoke frequently in defence of the slave trade 'denying the facts advanced, appealing to the prudence and policy of the House against their compassion'.

On 12 May 1789 he told the House that 'if they passed the vote of abolition they actually struck at seventy millions of property, they ruined the colonies, and by destroying an essential nursery of seamen, gave up the dominion of the sea at a single glance'.

His rhetoric was versatile; in 1794 he opposed William Wilberforce's bid to veto the export of slaves to foreign countries as an attack on private property.

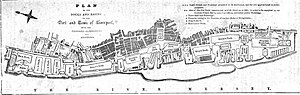

During the eighteenth century the town's population grew from some 6,000 to 80,000, and its land and water communications with its hinterland and other northern cities steadily improved.

One of the first Welsh-language journals, Yr Amserau, was founded in Liverpool by William Rees (Gwilym Hiraethog), and more than 50 Welsh chapels were constructed.

When the American Civil War broke out, Liverpool became a hotbed of intrigue, and Confederate agent James Dunwoody Bulloch set up a base of operations there.

[citation needed] The city was also the center of Confederate purchasing war materiel, including arms and ammunition, uniforms, and naval supplies to be smuggled by British blockade runners to the South.

By 1901, the city's population had grown to over 700,000, and its boundaries had expanded to include Kirkdale, Everton,[30] Walton, West Derby (in 1835 and 1895), Toxteth and Garston.

Economic changes began in the first part of the 20th century, as falls in world demand for the North West's traditional export commodities contributed to stagnation and decline in the city.

This was combated by a large amount of housing mostly built by the local council being constructed, creating jobs mostly in the building, plumbing and electrical trades.

[9] In July 1981 the infamous Toxteth Riots took place, during which, for the first time in the UK outside Northern Ireland, tear gas was used by police against civilians.

This had a traumatic effect on people across the country, particularly in and around the city of Liverpool, and resulted in legally imposed changes in the way in which football fans have since been accommodated, including compulsory all-seater stadiums at all leading English clubs by the mid-1990s.

It has since become clear that South Yorkshire Police made a range of mistakes at the game, though the senior officer in charge of the event retired soon after.

Everton have enjoyed an unbroken run in the top flight of English football since 1954, although their only major trophy since the league title in 1987 came in 1995 when they won the FA Cup.

[45] A similar national outpouring of grief and shock to the Hillsborough disaster occurred in February 1993 when James Bulger was killed by two ten-year-old boys, Jon Venables and Robert Thompson.

In June 2003, Liverpool won the right to be named European Capital of Culture for 2008, beating other British cities such as Newcastle and Birmingham to the coveted title.