History of Milton Keynes

[1] In the 1960s, the UK Government decided that a further generation of new towns in the South East of England was needed to relieve housing congestion in London.

[21] In the same area, an unusually large (18-metre or 59-foot diameter) round house was excavated and dated to the Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age, about 700 BCE.

[25][24][b] Before the Roman conquest of Britain of 43 CE, the Catuvellauni (a British Iron Age tribe) controlled this area from their hillfort at Danesborough,[c] near Woburn Sands.

[28] Further excavations revealed that this area, overlooking the fertile valley of the Bradwell Brook, was in continuous occupation for 2,000 years, from the Late Bronze Age to the early Saxon period.

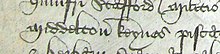

[35] The Domesday Book of 1086 provides the first documentary evidence for many settlements, listing Bertone (Broughton), Calvretone (Calverton), Linforde (Great Linford), Lochintone (Loughton), Neuport (Newport Pagnell), Nevtone (Newton Longville), Senelai (Shenley), Siwinestone (Simpson), Ulchetone (Woughton), Waletone (Walton), Wluerintone (Wolverton) and Wlsiestone (Woolstone).

[36] Bletchley, Bradwell, Calverton, Fenny Stratford, Great Linford, Loughton, Newport Pagnell, Newton Longville, Shenley (part of), Simpson, Stantonbury, Stoke Hammond, Stony Stratford, Water Eaton, Willen, Great and Little Woolstone, Wolverton, and Woughton on the Green were in Sigelai Hundred; Cold Brayfield, Castlethorpe, Gayhurst, Hanslope, Haversham, Lathbury, Lavendon, Little Linford, Olney, Ravenstone, Stoke Goldington, Tyringham with Filgrave, and Weston Underwood were in Bunstou Hundred; and Bow Brickhill, Great Brickhill, Little Brickhill, Broughton, Chicheley, Clifton Reynes, North Crawley, Emberton, Hardmead, Lathbury, Lavendon, Milton Keynes (village), Moulsoe, Newton Blossomville, Olney with Warrington, Ravenstone, Sherington, Stoke Goldington, Tyringham with Filgrave, Walton, Wavendon, Weston Underwood, and Willen were in Moulsoe Hundred.

[46][47] By the early 13th century, North Buckinghamshire had several religious houses: Bradwell Abbey (1154[48]) is within modern Milton Keynes and Snelshall Priory (1218[49]) is just outside it.

[34] The large oak beams forming the base supports still survived in the mill mound and were shown by radio carbon dating to originate in the first half of the 13th century.

[53] The oldest surviving domestic building is Number 22, Milton Keynes (village), the house of the bailiff of the manor of Bradwell.

[54] The desertion of Old Wolverton was due to enclosure of the large strip cultivation fields into small 'closes' by the local landlords, the Longville family, who turned arable land over to pasture.

Unfortunately, the heavy clay soils, poor drainage and slow-running streams made these routes frequently impassable in winter.

[30] Until about 1830, the London–Northampton road through Simpson "was generally impassible ['throughout a great portion of the winter'] without wading through water three feet deep (0.9m), for a distance of about 200 yards (180m)".

[60] In 1870, the new Northampton–London turnpike diverted away at Broughton to take the higher route through Wavendon and Woburn Sands to join Watling Street near Hockliffe.

[61] That traffic came to an abrupt end in 1838 when the London and Birmingham Railway (now the West Coast Main Line) opened through nearby Wolverton.

[66] In Stony Stratford, expertise learned in the works was applied to the construction of traction engines for agricultural use and the site of the present Cofferidge Close was engaged in their manufacture.

With compulsory purchase, Bletchley Road (now renamed Queensway after a royal visit in 1966) became the new high street with wide pavements where front gardens once lay.

In the 1960s, the Government decided that a further generation of new towns in South East England was needed to take the projected population increase of London, after the initial 1940s/1950s wave.

[77][78][5] Buckinghamshire County Council's architect, Fred Pooley, had spent considerable time in the early sixties developing ideas for a new town in the Bletchley and Wolverton area.

He developed a futuristic proposal based on a monorail linking a series of individual high-rise townships to a major town centre.

In 1967, the designated area outside the four main towns (Bletchley, Newport Pagnell, Stony Stratford, Wolverton) was largely rural farmland but included many picturesque North Buckinghamshire villages and hamlets: Bradwell village and Abbey, Broughton, Caldecotte, Fenny Stratford, Great Linford, Loughton, Milton Keynes Village, New Bradwell, Shenley Brook End, Shenley Church End, Simpson, Stantonbury, Tattenhoe, Tongwell, Walton, Water Eaton, Wavendon, Willen, Great and Little Woolstone, Woughton on the Green.

The goals declared in the master plan were these:[17]The designers were determined to learn from the mistakes made in the earlier new towns and revisit the Garden City ideals.

[86][89] They set in place the characteristic grid roads that run between districts, the Redway system of independent cycle/pedestrian paths, and the intensive planting, lakes and parkland that are so appreciated today.

[91] The radical grid plan was inspired by the work of Californian urban theorist Melvin M Webber (1921–2006), described by the founding architect of Milton Keynes, Derek Walker, as the city's "father".

[93] Urban design Since the radical plan form and large scale of the New City attracted international attention, early phases of the city include work by celebrated architects, Sir Richard MacCormac,[94] Lord Norman Foster,[95] Henning Larsen,[96] Ralph Erskine,[97] John Winter,[98] and Martin Richardson.

[102] Though strongly committed to sleek 'Miesian minimalism' inspired by the German/ American architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, they also developed a strand of contextualism in advance of the wider adoption of commercial Post-Modernism as an architectural style in the 1980s.

The contextual tradition that ran alongside it is exemplified by the corporation's infill scheme at Cofferidge Close, Stony Stratford, designed by Wayland Tunley, which inserts into a historic stretch of High Street a modern retail facility, offices and car park.

The Parks Trust is endowed with a portfolio of commercial properties, the income from which pays for the upkeep of the green spaces, a citywide maintenance model which has attracted international attention.

This programme also had two strands: a populist one which involved the local community in the works, the most famous of which is Liz Leyh's Concrete Cows,[104] a group of concrete Friesian cows which have become the unofficial logo of the city; and a tradition of abstract geometrical art, such as Lilliane Lijn's Circle of Light hanging in the Midsummer Arcade of the Central Milton Keynes shopping centre.

Demographics Unusually for a new town, Milton Keynes has arrived at a bias in favour of private sector investment, with about 80% of owner-occupied homes.

This phase of development lasted until EP was wound up in 2008 and in that time had specified substantial expansions to the east (Broughton and Brooklands) and to the west (Whitehouse and Fairfields), as well as intensification of the city centre.