History of Lowell, Massachusetts

The history of Lowell, Massachusetts, is closely tied to its location along the Pawtucket Falls of the Merrimack River, from being an important fishing ground for the Pennacook tribe[1] to providing water power for the factories that formed the basis of the city's economy for a century.

During the 1640s, Major Simon Willard traded extensively with the tribes, and in 1647 was accompanied in his expedition by the noted preacher John Eliot.

[8] Subsequent grants of land extended the town to cover most of the territory Lowell now occupies, with the exception of 500 acres of farmland reserved for the Pawtucket.

Wannalancit, the son of Passaconaway and the Pawtucket leader after his father's retirement, took the surviving tribesmen and moved to Wickassee before selling the land in 1686.

The presence of Pawtucket Falls offered a source of water power that enabled the construction of a sawmill and gristmill in the early 18th century,[14] followed by a fulling mill in 1737.

Because British law prohibited the export of the machines, Lowell instead memorized the designs, and on his return helped build a replica.

This mill was the first one in America to use power looms, and proved so successful that Patrick Jackson (Lowell's successor after his death in 1817) saw a need to open a new plant.

[21] Jackson and others founded the Merrimack Manufacturing Company to open a mill by Pawtucket Falls, breaking ground in 1822 and completing the first run of cotton in 1823.

[24] Within a decade the population jumped from 2,500 to 18,000, and on April 1, 1836, the town of Lowell officially received a charter as a city, granted by the Massachusetts General Court.

The 5.6 mile long canal system produced 10,000 horsepower, being provided to ten corporations with a total of forty mills.

In 1828, Paul Moody developed an early belt-driven power transfer system to supersede the unreliable gearwork that was utilized at the time.

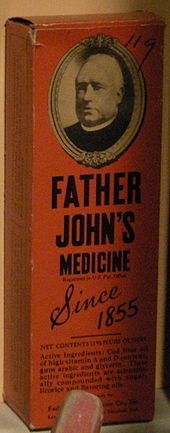

It opened five years became independent in 1845, patent medicine factories like Hood's Sarsaparilla Laboratory later, making the Middlesex Canal obsolete.

The turbine was improved at Lowell again shortly thereafter by Englishman James B. Francis, chief engineer of Proprietors of Locks and Canals.

Tyler Park and Lynde Hill in Belvidere were home to many of Lowell's wealthiest residents, who could now live away from the noisy and polluted downtown industrial area.

A new library with a hall dedicated to the Civil War, a post office, and ornate commercial buildings replaced the puritanical mid-century structures.

The reason was largely because their seaport locations made the importation and exportation of goods and materials, and particularly coal, more economical than the considerably inland, and therefore only accessible by train, Lowell.

In its place, large, densely populated ethnic neighborhoods grew around the city, their residents more rooted in their churches, organizations, and communities than the previous era's company boardinghouse dwellers.

The American Civil War shut down many of the mills temporarily when they sold off their cotton stockpiles, which had become more valuable than the finished cloth after imports from the South had stopped.

Lowell had a small historical place in the war: Many wool Union uniforms were made in Lowell, General Benjamin Franklin Butler was from the city, and members of the Lowell-based Massachusetts Sixth—Ladd, Whitney, Taylor, and Needham—were the first four Union deaths, killed in a riot while passing through Baltimore on their way to Washington, DC.

Later French Canadian immigrants included the parents of famed Beat generation writer Jack Kerouac, a native of the city.

Although the South did not have rivers capable of providing the waterpower needed to run the early mills, the advent of steam-powered factories allowed companies to take advantage of the cheaper labor and transportation costs available there.

World War II again briefly helped the economy, since not only did demand for clothing go up, but Lowell was involved in munitions manufacturing.

As the car took over American life after World War II, the downtown, which already was facing problems due to a drop in expendable income, was largely vacated as business moved to suburban shopping malls.

Others had their top floors removed to reduce tax bills and many facades were "modernized" destroying the Victorian character of the downtown.

The construction of the Lowell Connector around 1960 was surprisingly unintrusive for an urban interstate, but that was only because plans to extend it to East Merrimack Street by way of Back Central and the Concord Riverfront were cancelled.

However, the demolition and decay of much of what had made Lowell a vibrant city led some residents to begin thinking about saving the historical structures.

Many residents of Lowell viewed the city's industrial history poorly - the factories had abandoned their workers, and now sat empty and in disrepair.

[35] Combined with other immigrant groups like Puerto Ricans, Greeks and French Canadians, these newcomers brought the city's population back up to six figures.

[citation needed] The HBO special, High on Crack Street: Lost Lives in Lowell was filmed in 1995 which tended to emphasize the reputation of the city as a dangerous and depressed place to be.

The Invention of Lying was released in September 2009, and shortly before, filming on The Fighter, about Lowell boxing legend Micky Ward and his older brother Dicky Eklund, was completed.