History of Palau

The islands were then visited by the Jesuit expedition led by Francisco Padilla on 30 November 1710, who left two priests Jacques Du Beron and Joseph Cortyl stranded on the coast of Sonsorol, while the mother ship Santissima Trinidad was swept away by a storm.

[4] The construction and maintenance of terraces on the volcanic islands appears to precede the formation of the formal, nucleated, settlements observed at European contact in 1783.

The location and organizational characteristics of habitations associated with terraces appear to have been, to some extent, different than that of the historic pattern of traditional villages in coastal areas.

Some of these middens, especially from the Uchularois Cave Site, contain large quantities of artifacts, suggesting that they are the result of the intensive exploitation of marine resources, shellfish in particular.

Evidence from legends and the tight clustering of the radiocarbon dates suggests that the villages were abandoned abruptly early in the 15th century.

The large stone features recorded in village sites have specific historic references in the oral tradition of Palau.

Clan lands continue to be passed through titled women and first daughters[6] but there is also a modern patrilineal sentiment introduced by imperial Japan.

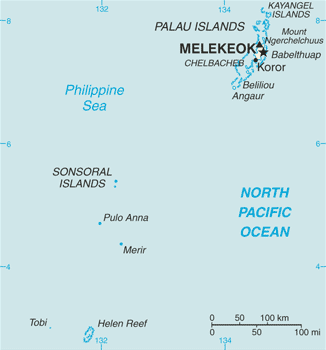

There is disagreement as to whether Spaniard Ruy López de Villalobos, who landed in several Caroline Islands, spotted the Palau archipelago in 1543.

This map and the letter caused a vast interest in the new islands and resulted in the first and failed Jesuit attempts to travel to Palau from the Philippines in 1700, 1708 and 1709.

[1] The islands were first visited by the Jesuit expedition led by Francisco Padilla on 30 November 1710, only to leave two stranded priests Jacques Du Beron and Joseph Cortyl on the coast of Sonsorol, while the mother ship Santissima Trinidad was being swept away by a storm.

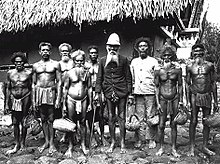

Englishman Henry Wilson, captain of the East India Company's packet ship Antelope, was shipwrecked off the island of Ulong in 1783.

The High Chief of (Koror) Palau allowed Captain Wilson to take his son, Prince Lee Boo, to England, where he arrived in 1784.

The wreck of the Antelope began European intervention in Palauan affairs and marked the beginning of nearly two centuries of colonial domination of the islands .

By this time the focus of trepang production had shifted to the Philippines and Indonesia, and Palau no longer played an important role.

[4] After being defeated in 1898 in the Spanish–American War and losing possession of the Philippine Islands, Spain sold the Palau archipelago to Imperial Germany in the 1899 German–Spanish Treaty.

German engineers began exploiting the islands' deposits of bauxite and phosphate, and a rich harvest in copra was made.

Also, perhaps as important as the economic development, the German Administration began pushing for social reforms which included the relocation of people into larger villages and a large number of public works projects such as the construction of piers and navigation beacons.

Large numbers of Japanese and Ryukyuans were encouraged to emigrate to Micronesia to work on plantations or in other economic enterprises, resulting in Palau becoming a major colonial center.

Japan mounted an aggressive economic development program and promoted large scale immigration by Japanese, Ryukyuans and Koreans.

The Japanese continued the German mining activities, and also established bonito (skipjack tuna) canning and copra processing plants in Palau.

Japanese trading companies were quick to establish operations to exploit the economic potential of the islands, especially the abundant fish resources and pearl harvesting.

The Japanese established a commercial center in Koror, and began developing a series of agricultural plantations on Babeldaob Island.

Despite the substantial improvements made in social services for the Palauans, the Japanese were quite clear on the role and status of the native peoples in Micronesia.

The Japanese began to relocate large numbers of Palauans from the larger towns on Orcor and Beliliou to villages on Babeldaob Island.

Making use of the large number of natural openings in the coralline limestone formations, the Japanese had created a defensive fortress of interlocking tunnels, bunkers, and hardened gun positions where more than 10,000 defenders could safely wait out the naval bombardment.

Following the bloody experience on Beliliou, U.S. military planners were content to bypass the 30,000 or so Japanese troops remaining in Koror and Babeldaob.

Starting in 1993, a small group of American volunteers called The BentProp Project has searched the waters and jungles of Palau for information that could lead to the identification and recovery of these remains.

In 1947, the United States, as the post-World War II occupying power, agreed to administer Palau as part of the U.N.-created Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI).

After many years of talks on a post-trust status for Palau, the U.S. Congress in 1986 approved a Compact of Free Association agreed to by U.S. and Palauan negotiators.

After adoption of a constitutional amendment and a long period of transition, including the violent deaths of two presidents (Haruo Remeliik in 1985 and Lazarus Salii in 1988), Palau's courts ruled that the 68% pro-compact vote in an eighth referendum—held November 9, 1993—was sufficient to approve the compact.