Manila galleon

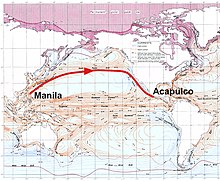

Urdaneta and Alonso de Arellano made the first successful round trips that year, by taking advantage of the Kuroshio Current.

The return route from Acapulco passes through lower latitudes closer to the equator, stopping over in the Marianas, then sailing onwards through the San Bernardino Strait off Cape Espiritu Santo in Samar and then to Manila Bay and anchoring again off Cavite by June or July.

The majority of these galleons were built and loaded in shipyards in Cavite, utilizing native hardwoods like the Philippine teak, with sails produced in Ilocos, and with the rigging and cordage made from salt-resistant Manila hemp.

The vast majority of the galleon's crew consisted of Filipino natives; many of whom were farmers, street children, or vagrants press-ganged into service as sailors.

[3] These goods included Indian ivory and precious stones, Chinese silk and porcelain, cloves from the Moluccas islands, cinnamon, ginger, lacquers, tapestries and perfumes from all over Asia.

Although Magellan was killed by natives commanded by Lapulapu during the battle of Mactan in the Philippines, one of his ships, the Victoria, made it back to Spain by continuing westward.

The frustration of these failures is shown in a letter sent in 1552 from Portuguese Goa by the Spanish missionary Francis Xavier to Simão Rodrigues asking that no more fleets attempt the New Spain–East Asia route, lest they be lost.

[11] Despite prior failures navigator Andrés de Urdaneta effectively persuaded Spanish officials in New Spain that a Philippines-Mexico trade route was preferrable to other alternatives.

Sailing as part of the expedition commanded by Miguel López de Legazpi to conquer the Philippines in 1564, Urdaneta was given the task of finding a return route.

Although the ship's log and other records were lost, the officially accepted location is now called Drakes Bay, on Point Reyes south of Cape Mendocino.

According to historian William Lytle Schurz, "They generally made their landfall well down the coast, somewhere between Point Conception and Cape San Lucas ... After all, these were preeminently merchant ships, and the business of exploration lay outside their field, though chance discoveries were welcomed".

Cargoes varied from one voyage to another but often included goods from all over Asia: jade, wax, gunpowder and silk from China; amber, cotton and rugs from India; spices from Indonesia and Malaysia; and a variety of goods from Japan, the Spanish part of the so-called Nanban trade, including Japanese fans, chests, screens, porcelain and lacquerware.

[31] In addition, slaves of various origins, including East Africa, Portuguese India, the Muslim sultanates of Southeast Asia, and the Spanish Philippines, were transported from Manila and sold in New Spain.

The transport of goods overland by porters, the housing of travelers and sailors at inns by innkeepers, and the stocking of long voyages with food and supplies provided by haciendas before departing Acapulco helped to stimulate the economy of New Spain.

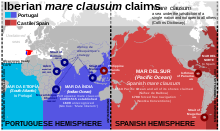

[31] This Pacific route was the alternative to the trip west across the Indian Ocean, and around the Cape of Good Hope, which was reserved to Portugal according to the Treaty of Tordesillas.

They tried to establish a regular land crossing there, but the thick jungle and tropical diseases such as yellow fever and malaria made it impractical.

[citation needed] It took at least four months to sail across the Pacific Ocean from Manila to Acapulco, and the galleons were the main link between the Philippines and the viceregal capital at Mexico City and thence to Spain itself.

If the expedition was successful the voyagers would go to La Ermita (the church) to pay homage, and offer gold and other precious gems or jewelries from Hispanic countries to the image of the virgin.

In 1740, as part of the administrative changes of the Bourbon Reforms, the Spanish crown began allowing the use of registered ships or navíos de registro in the Pacific.

While these solo voyages would not immediately replace the galleon system, they were more efficient and better able to avoid being captured by the Royal Navy of Great Britain.

[37] In 1813, the Cortes of Cádiz decreed the suppression of the route and the following year, with the end of the Peninsular War, Ferdinand VII of Spain ratified the dissolution.

Sea transport became easier in the mid-19th century after the invention of steam powered ships and the opening of the Suez Canal, which reduced the travel time from Spain to the Philippines to 40 days.

In Acapulco, the arrival of the galleons provided seasonal work, as for dockworkers who were typically free black men highly paid for their back breaking labor, and for farmers and haciendas across Mexico who helped stock the ships with food before voyages.

In 1568, Miguel López de Legazpi's own ship, the San Pablo (300 tons), was the first Manila galleon to be wrecked en route to Mexico.

British historian Henry Kamen maintains that the Spanish did not have the ability to properly explore the Pacific Ocean and were not capable of finding the islands which lay at a latitude 20° north of the westbound galleon route and its currents.

This navigational activity poses the question as to whether Spanish explorers did arrive in the Hawaiian Islands two centuries before Captain James Cook's first visit in 1778.

Ruy López de Villalobos commanded a fleet of six ships that left Acapulco in 1542 with a Spanish sailor named Ivan Gaetan or Juan Gaetano aboard as pilot.

According to Hawaiian writer Herb Kawainui Kane, one of these stories: concerned seven foreigners who landed eight generations earlier at Kealakekua Bay in a painted boat with an awning or canopy over the stern.

[56] In 2014, the idea to nominate the Manila–Acapulco Galleon Trade Route as a World Heritage Site was initiated by the Mexican and Filipino ambassadors to UNESCO.

[57] In 2015, the Unesco National Commission of the Philippines (Unacom) and the Department of Foreign Affairs organized an expert's meeting to discuss the trade route's nomination.