History of Roman-era Tunisia

Many large mosaics formed the floors of courtyards and rooms in villas within Carthage and the countryside,[7] Beyond the city, many pre-existing Punic and Berber towns found fresh vigor and prosperity.

An ancient epitaph here celebrates Vincentius, a popular pantomime (quoted in part): He lives forever in the thoughts of the people... just, good and in his every relationship with each person irreproachable and sure.

The quality and extent of large villas with comfort amenities, and other farm housing, found throughout Africa Province dating to this era, evince the wealth generated by agriculture.

Olives and grapes had for long been popular products commonly praised; however, the vineyards and orchards had been devastated during the last Punic war; also they were intentionally left to ruin because their produce competed with that of Roman Italia.

[25] Ceramics and pottery, skills developed and practiced for many centuries under the prior Phoenician-derived, urban culture, continued as an important industry,[26] Both oil lamps and amphorae (containers with two handles) were produced in quantity.

Much of this industry was located in central Tunisia, e.g., in and around Thysdrus (modern El Djem), a drier area with less fertile agricultural lands, but ample in rich clay deposits.

These imperial distinctions overlay the preexisting stratification of economic classes, e.g., there continued the practice of slavery, and there remained a coopted remnant of the wealthy Punic aristocracy.

[49][50] In 238 local proprietors rose in revolt, arming their clients and agricultural tenants who entered Thysdrus (modern El Djem) where they killed a rapacious official and his bodyguards.

"[57] Later Julian authored his Digesta in 90 books; this work generally followed the sequence of subjects found in the praetorian edict, and presented a "comprehensive collection of responsa on real and hypothetical cases".

While returning to Carthage he fell seriously ill in Oea (an ancient coastal city near modern Tripoli), where he convalesced at the family home of an old student friend Pontianus.

[71] He showed brilliance speaking in public as a "popular philosopher or 'sophist', characteristic of the second century A.D., which ranked such talkers higher than poets and rewarded them greatly with esteem and cash...

[80][81] After such and many adventures, in which he finds comedy, cruelty, onerous work as a beast-of-burden,[82] circus-like exhibition, danger, and a love companion, the hero finally manages to regain his human form—by eating roses.

My rugged hair thinned and fell; my huge belly sank in; my hooves separated out into fingers and toes; my hands ceased to be feet... and my tail... simply disappeared.

He also notes that at the end of Metamorphoses "we find the only full testimony of religious experience left by an adherent of ancient paganism... devotees of mystery-cults, of the cults of the savior-gods...

Rose comments that "the story is meant to convey a religious lesson: Isis saves [the hero] from the vanities of this world, which make men of no more worth than beasts, to a life of blissful service, here and hereafter.

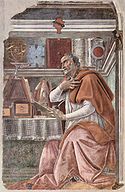

Referring to what he found as moral confusion or worse in stories of these gods,[92] and their airy spirits, Augustine suggests a better title for Apuleius' book: "he should have called it De Daemone Socratis, of his devil.

[101] The Roman Imperial cult was based on a general polytheism that, by combining veneration for the paterfamilias and for the ancestor, developed a public celebration of the reigning Emperor as a father and divine leader.

This turnabout led to confusion within the Church; in Northwest Africa this accentuated the divide between wealthy urban members aligned with the Empire, and the local rural poor who were salt-of-the-earth believers (which included as well social and political dissidents).

[137] A disorderly, rural extremist group became associated with the Donatists, the circumcellions, who opposed taxes, debt collection, and slavery, and would obstruct normal commerce in order to protect the poor.

Although enjoying maybe "unquestioningly loyal tribesmen on [their] great estates" the nobles themselves held a divided loyalty stemming from their ambivalent role as mediators between Roman Empire elites and local tribal life, mostly rural.

[148] Another view holds that the nobles Firmus and Gildo each continued the struggle of the commoner Tacfarinas, that the fight involved class issues and pitted Berber against Roman.

The conflicts were part of the long effort by native agricultural people to reclaim their farming and pasture lands, seized by the Romans as a result of military victories.

[153][154][155] Nubel the father held three positions: influential leader in Berber tribal politics; Roman official with high connections; and, private master of large land holdings.

[184] These changes were traumatic to Roman citizens in Africa Province including, of course, those acculturated Berbers who once enjoyed the prospects for livelihood provided by the long fading, now badly broken Imperial economy.

This "pre-Sahara" geographic and cultural zone ran along the mountainous frontier, the Tell, hill country and upland plains, which separated the "well-watered, Mediterranean districts of the Maghreb to the north, from the Sahara desert to the south."

[185] From west to east across Northwest Africa, eight of these new Berbers states have been identified, being the kingdoms of: Altava (near present-day Tlemcen); the Ouarsenis (by Tiaret); Hodna; the Aures (southern Numidia); the Nemencha; the Dorsale (at Thala, south of El Kef); Capsus (at Capsa); and, Cabaon (in Tripolitania, at Oea).

This functional and ethnic duality at the core of the Berber successor states is reflected in the title of the political leader at Altava (see here above), one Masuna, found on an inscription: rex gent(ium) Maur(orum) et Romanor(um).

"While their architectural form echoes a long tradition of massive Northwest African royal mausolea, stretching back to Numidian and Mauretanian kingdoms of the 3rd–1st centuries BC, the closest parallels are with the tumuli or bazinas, with flanking 'chapels', which are distributed in an arc through the pre-Saharan zone and beyond" perhaps several thousand kilometers to the southwest (to modern Mauritania).

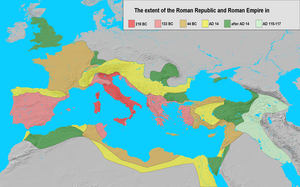

In 429 under their king Gaiseric (r. 428–477) the Vandals and the Alans (their Iranian allies), about 80,000 people, traveled the 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) from Iulia Traducta in Andalusia across the straits and east along the coast to Numidia, west of Carthage.

[211] Following the Arab invasion and occupation of Egypt in 640, there were Christian refugees who fled west, until arriving in the Exarchate of Africa (Carthage), which remained under Byzantine rule.