History of archery

[2] Archers were a widespread if supplemental part of the military in the classical period, and bowmen fought on foot, in chariots or mounted on horses.

Archery rose to prominence in Europe in the later medieval period, where victories such as the Battle of Agincourt cemented the longbow in military lore.

[3][4] Archery in both hunting and warfare was eventually replaced by firearms in Europe in the Late Middle Ages and early modern period.

[6] The oldest known evidence of arrows comes from South African sites such as Sibudu Cave, where likely arrowheads have been found, dating from approximately 72,000–60,000 years ago,[7][8][9][10][11][12] on some of which poisons may have been used.

"Bow-and-arrow hunting at the Sri Lankan site likely focused on monkeys and smaller animals, such as squirrels... Remains of these creatures were found in the same sediment as the bone points.

They were often rather long, up to 120 cm (4 ft) and made of European hazel (Corylus avellana), wayfaring tree (Viburnum lantana) and other small woody shoots.

[citation needed] The oldest depictions of combat, found in Iberian cave art of the Mesolithic, show battles between archers.

[32][33][34] Chariot-borne archers became a defining feature of Middle Bronze Age warfare, from Europe to Eastern Asia and India.

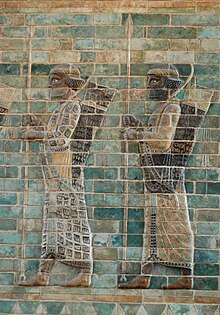

Ancient civilizations, notably the Persians, Parthians, Egyptians, Nubians, Indians, Koreans, Chinese, and Japanese fielded large numbers of archers in their armies.

The nomads from the Eurasian steppes are believed to play an integral part in introducing the composite bow to other civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Iran, India, East Asia, and Europe.

Besides providing the account of the training of the archers, Vasiṣṭha's Dhanurveda describes the different types of bows and arrows, as well as the process of making them.

Vikings made extensive use of shortbows both on land and at sea, but other early medieval armies less so, with some notable exceptions.

Crossbows generally had a longer range, greater accuracy and more penetration than the shortbow, but suffered from a much slower rate of fire.

In the Scottish Highlands, archers were used in battle until 1689 at Killiekrankie, with a documented fatal shot from the Hanoverian Government army.

[59] Turkish tribes, of which the Seljuk Turks are representative, used mounted archers against the European First Crusade, especially at the Battle of Dorylaeum (1097).

[59] Mongol bows of that period were constructed from leather, horn, and wood with animal sinew outside, held together with fish glue and covered with tree bark to protect against water.

[49][50] The Sasanian general Bahram Chobin has been credited with writing a manual of archery in the tenth century in Ibn al-Nadim's catalogue Kitab al-Fihrist.

[68] A 14th-century treatise on Arab archery, Kitāb fī maʿrifat ʿilm ramy al-sihām, was written by Hussain bin Abd al-Rahman.

[70] An anonymous book written in Picardy, France, in the late 15th century details how archery in medieval Europe was practiced.

"[74] Early firearms were inferior in rate of fire (a Tudor English author expects eight shots from the English longbow in the time needed for a "ready shooter" to give five from the musket),[75] and François Bernier reports that well-trained mounted archers at the Battle of Samugarh in 1658 were "shooting six times before a musketeer can fire twice".

[81] Archery continued in some areas that were subject to limitations on the ownership of arms, such as the Scottish Highlands during the repression that followed the decline of the Jacobite cause, and the Cherokees after the Trail of Tears.

The Tokugawa shogunate severely limited the import and manufacture of guns, and encouraged traditional martial skills among the samurai; towards the end of the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877, some rebels fell back on the use of bows and arrows.

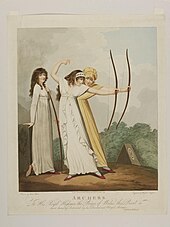

Sir Ashton Lever, an antiquarian and collector, formed the Toxophilite Society in London in 1781, with the patronage of George, the Prince of Wales.

Recreational archery soon became extravagant social and ceremonial events for the nobility, complete with flags, music and 21 gun salutes for the competitors.

The clubs were "the drawing rooms of the great country houses placed outside" and thus came to play an important role in the social networks of local elites.

Archery was also co-opted as a distinctively British tradition, dating back to the lore of Robin Hood and it served as a patriotic form of entertainment at a time of political tension in Europe.

After the Napoleonic Wars, the sport became increasingly popular among all classes, and it was framed as a nostalgic reimagining of the preindustrial rural Britain.

Particularly influential was Sir Walter Scott's 1819 novel, Ivanhoe that depicted the heroic character Locksley winning an archery tournament.

The first Grand National Archery Society meeting was held in York in 1844 and over the next decade the extravagant and festive practices of the past were gradually whittled away and the rules were standardised as the 'York Round' – a series of shoots at 60, 80, and 100 yards.

[91] In China, at the beginning of the 21st century, there has been revival in interest among craftsmen looking to construct bows and arrows, as well as in practicing technique in the traditional Chinese style.