History of atheism

Who then knows whence it has arisen?In the East, a contemplative life not centered on the idea of deities began in the sixth century BCE with the rise of Jainism, Buddhism, and various sects of Hinduism in India, and of Taoism in China.

Already in the sixth century BCE Ajita Kesakambalin was quoted in Pali scriptures by the Buddhists with whom he was debating, teaching that "with the break-up of the body, the wise and the foolish alike are annihilated, destroyed.

In the book More Studies on the Cārvāka/Lokāyata (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020) Ramkrishna Bhattacharya argues that there have been many varieties of materialist thought in India; and that there is no foundation to the accusations of hedonism nor to the claim that these schools reject inference (anumāna) per se as a way of knowledge (pramāṇas).

[31] The Tattvopaplavasimha of Jayarashi Bhatta (c. 8th century) is sometimes cited as a surviving Carvaka text, as Ethan Mills does in Three Pillars of Skepticism in Classical India: Nagarjuna, Jayarasi, and Sri Harsa (2018).

According to the chronicler Abul Fazl (1551–1602), those discussing religious and existential matters at Akbar's court included the atheists: They do not believe in a God nor in immaterial substances, and affirm faculty of thought to result from the equilibrium of the aggregate elements (…) They admit only of such sciences as tend to the promotion of external order, that is, a knowledge of just administration and benevolent government.

There are, however, "gods" and other spirits who exist within the universe and Jains believe that the soul can attain "godhood"; however, none of these supernatural beings exercise any sort of creative activity or have the capacity or ability to intervene in answers to prayers.

[52] The first fully materialistic philosophy was produced by the atomists Leucippus and Democritus (5th century BCE), who attempted to explain the formation and development of the world in terms of the chance movements of atoms moving in infinite space.

[71] Euhemerus (c. 330–260 BCE) published his view that the gods were only the deified rulers, conquerors, and founders of the past, and that their cults and religions were in essence the continuation of vanished kingdoms and earlier political structures.

[72] Although Euhemerus was later criticized for having "spread atheism over the whole inhabited earth by obliterating the gods",[73] his worldview was not atheist in a strict and theoretical sense, because he differentiated them from the primordial deities, holding that they were "eternal and imperishable".

People described as goðlauss expressed not only a lack of faith in deities, but also a pragmatic belief in their own faculties of strength, reason and virtue and in social codes of honor independent of any supernatural agency.

Pope Boniface VIII, because he insisted on the political supremacy of the church, was accused by his enemies after his death of holding (unlikely) positions such as "neither believing in the immortality nor incorruptibility of the soul, nor in a life to come".

[90] The concept of atheism re-emerged initially as a reaction to the intellectual and religious turmoil of the Age of Enlightenment and the Reformation, as a charge used by those who saw the denial of god and godlessness in the controversial positions being put forward by others.

Deism gained influence in France, Prussia and England, and proffered belief in a noninterventionist deity, but "while some deists were atheists in disguise, most were religious, and by today's standards would be called true believers".

In 1661 he published his Short Treatise on God, but he was not a popular figure for the first century following his death: "An unbeliever was expected to be a rebel in almost everything and wicked in all his ways", wrote Blainey, "but here was a virtuous one.

[105] Voltaire's assertion occurs in his Épître à l'Auteur du Livre des Trois Imposteurs, written in response to the Treatise of the Three Impostors, a document (most likely) authored by John Toland that denied all three Abrahamic religions.

[106] In 1766, Voltaire tried unsuccessfully to have the judgment reversed in the case of the French nobleman François-Jean de la Barre who was tortured, beheaded, and his body burned for alleged vandalism of a crucifix.

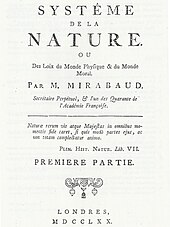

Arguably the first book in modern times solely dedicated to promoting atheism was written by French Catholic priest Jean Meslier (1664–1729), whose posthumously published lengthy philosophical essay (part of the original title: Thoughts and Feelings of Jean Meslier ... Clear and Evident Demonstrations of the Vanity and Falsity of All the Religions of the World[107]) rejects the concept of God (both in the Christian and also in the Deistic sense), the soul, miracles and the discipline of theology.

D'Holbach was a Parisian social figure who conducted a famous salon widely attended by many intellectual notables of the day, including Denis Diderot, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume, Adam Smith, and Benjamin Franklin.

[110] The culte de la Raison developed during the uncertain period 1792–94 (Years I and III of the Revolution), following the September massacres, when Revolutionary France was rife with fears of internal and foreign enemies.

In the cathedral of Notre Dame the altar, the holy place, was converted into a monument to Reason..." During the Terror of 1792–93, France's Christian calendar was abolished, monasteries, convents and church properties were seized and monks and nuns expelled.

The pamphlet Answer to Dr. Priestley's Letters to a Philosophical Unbeliever (1782) is considered to be the first published declaration of atheism in Britain—plausibly the first in English (as distinct from covert or cryptically atheist works).

Born in 1792, Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, a child of the Age of Enlightenment, was expelled from England's Oxford University in 1811 for submitting to the Dean an anonymous pamphlet that he wrote entitled, The Necessity of Atheism.

[117] Atheism in the twentieth century found recognition in a wide variety of other, broader philosophies in the Western tradition, such as logical positivism, Marxism, anarchism, existentialism, secular humanism, objectivism,[118] feminism,[119] and the general scientific and rationalist movement.

[123] Following the death of Vladimir Lenin, with his rejection of religious authority as a tool of oppression and his strategy of "patently explain," Soviet leader Joseph Stalin pursued the persecution of the church through the 1920s and 1930s.

[131][132] In practice, however, the Nazi regime worked to reduce the influence of Christianity in Germany, seeing it as a barrier to their taking over associations and schools belonging to the churches as part of their path of total control over society.

Science, he declared, would easily destroy the last remaining vestiges of superstition ... 'In the long run', [Hitler] concluded in July 1941, 'National Socialism and religion will no longer be able to exist together' [...

[138] Heinrich Himmler was a strong promoter of the gottgläubig movement and did not allow atheists into the SS, arguing that their "refusal to acknowledge higher powers" would be a "potential source of indiscipline".

[160][161] The early twenty-first century has continued to see secularism, humanism and atheism promoted in the Western world, with the general consensus being that the number of people not affiliated with any particular religion has increased.

[162][163] Atheist organizations aim to promote public understanding and acknowledgment of science through a naturalistic, scientific worldview,[164] defense of irreligious people's human, civil and political rights who share it, and their societal recognition.

[165] In addition, a large number of accessible atheist books, many of which have become bestsellers, have been published by scholars and scientists such as Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Christopher Hitchens, Lawrence M. Krauss, Jerry Coyne, and Victor J.