Ancient Egyptian religion

Egyptian belief in the afterlife and the importance of funerary practices is evident in the great efforts made to ensure the survival of their souls after death – via the provision of tombs, grave goods and offerings to preserve the bodies and spirits of the deceased.

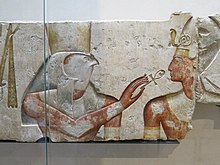

[5] It could include gods adopted from foreign cultures, and sometimes humans: deceased pharaohs were believed to be divine, and occasionally, distinguished commoners such as Imhotep also became deified.

The Egyptians sought to maintain Ma'at in the cosmos by sustaining the gods through offerings and by performing rituals which staved off disorder and perpetuated the cycles of nature.

[18][19] When thinking of the shape of the cosmos, the Egyptians saw the earth as a flat expanse of land, personified by the god Geb, over which arched the sky goddess Nut.

[25] However, the pharaoh's real-life influence and prestige could differ from his portrayal in official writings and depictions, and beginning in the late New Kingdom his religious importance declined drastically.

[32] Over the course of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC), however, he came to be more closely associated with the daily rebirth of the sun god Ra and with the underworld ruler Osiris as those deities grew more important.

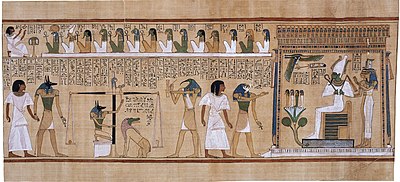

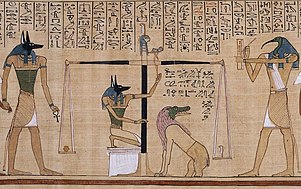

[33] In the fully developed afterlife beliefs of the New Kingdom, the soul had to avoid a variety of supernatural dangers in the Duat, before undergoing a final judgement, known as the "Weighing of the Heart", carried out by Osiris and by the Assessors of Ma'at.

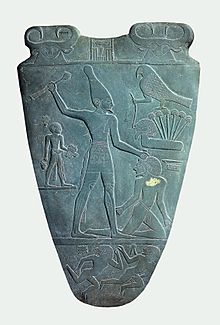

[50] Set's association with chaos, and the identification of Osiris and Horus as the rightful rulers, provided a rationale for pharaonic succession and portrayed the pharaohs as the upholders of order.

[57] Prayers follow the same general pattern as hymns, but address the relevant god in a more personal way, asking for blessings, help, or forgiveness for wrongdoing.

Such prayers are rare before the New Kingdom, indicating that in earlier periods such direct personal interaction with a deity was not believed possible, or at least was less likely to be expressed in writing.

They are a loose collection of hundreds of spells inscribed on the walls of royal pyramids during the Old Kingdom, intended to magically provide pharaohs with the means to join the company of the gods in the afterlife.

[61] At the end of the Old Kingdom a new body of funerary spells, which included material from the Pyramid Texts, began appearing in tombs, inscribed primarily on coffins.

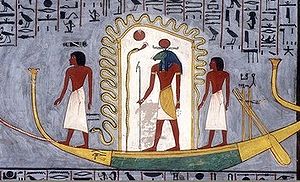

[65] Unlike the loose collections of spells, these netherworld books are structured depictions of Ra's passage through the Duat, and by analogy, the journey of the deceased person's soul through the realm of the dead.

[69] The earliest Egyptian temples were small, impermanent structures, but through the Old and Middle Kingdoms their designs grew more elaborate, and they were increasingly built out of stone.

During the Old and Middle Kingdoms, there was no separate class of priests; instead, many government officials served in this capacity for several months out of the year before returning to their secular duties.

[82] The most common means of consulting an oracle was to pose a question to the divine image while it was being carried in a festival procession, and interpret an answer from the barque's movements.

[83] While the state cults were meant to preserve the stability of the Egyptian world, lay individuals had their own religious practices that related more directly to daily life.

Personal piety became still more prominent in the late New Kingdom, when it was believed that the gods intervened directly in individual lives, punishing wrongdoers and saving the pious from disaster.

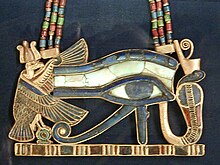

[91] The word "magic" is normally used to translate the Egyptian term heka, which meant, as James P. Allen puts it, "the ability to make things happen by indirect means".

In the Early Dynastic Period, however, they began using tombs for greater protection, and the body was insulated from the desiccating effect of the sand and was subject to natural decay.

Before the burial, these priests performed several rituals, including the opening of the mouth ceremony intended to restore the dead person's senses and give him or her the ability to receive offerings.

The tomb walls also bore artwork, such as images of the deceased eating food that were believed to allow him or her to magically receive sustenance even after the mortuary offerings had ceased.

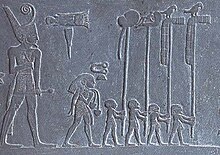

This event transformed Egyptian religion, as some deities rose to national importance and the cult of the divine pharaoh became the central focus of religious activity.

In contrast with the great size of the pyramid complexes, temples to gods remained comparatively small, suggesting that official religion in this period emphasized the cult of the divine king more than the direct worship of deities.

[122] By the Fifth Dynasty, Ra was the most prominent god in Egypt and had developed the close links with kingship and the afterlife that he retained for the rest of Egyptian history.

These Theban pharaohs initially promoted their patron god Montu to national importance, but during the Middle Kingdom, he was eclipsed by the rising popularity of Amun.

[134][135] In the 1st millennium BC, Egypt was significantly weaker than in earlier times, and in several periods foreigners seized the country and assumed the position of pharaoh.

Animal cults, a characteristically Egyptian form of worship, became increasingly popular in this period, possibly as a response to the uncertainty and foreign influence of the time.

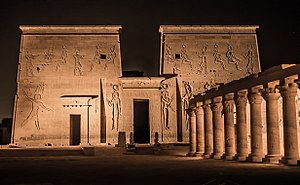

In fact, the fifth-century historian Priscus mentions a treaty between the Roman commander Maximinus and the Blemmyes and Nobades in 452, which among other things ensured access to the cult image of Isis.

[146][143] The letter warns of an unnamed man (the text calls him "eater of raw meat") who, in addition to plundering houses and stealing tax revenue, is alleged to have restored paganism at "the sanctuaries", possibly referring to the temples at Philae.