History of cryptography

[2] Some clay tablets from Mesopotamia somewhat later are clearly meant to protect information—one dated near 1500 BC was found to encrypt a craftsman's recipe for pottery glaze, presumably commercially valuable.

[16] The invention of the frequency analysis technique for breaking monoalphabetic substitution ciphers, by Al-Kindi, an Arab mathematician,[17][18] sometime around AD 800, proved to be the single most significant cryptanalytic advance until World War II.

[16] In early medieval England between the years 800–1100, substitution ciphers were frequently used by scribes as a playful and clever way to encipher notes, solutions to riddles, and colophons.

For instance, in Europe during and after the Renaissance, citizens of the various Italian states—the Papal States and the Roman Catholic Church included—were responsible for rapid proliferation of cryptographic techniques, few of which reflect understanding (or even knowledge) of Alberti's polyalphabetic advance.

[26] The chief cryptographer of King Louis XIV of France was Antoine Rossignol; he and his family created what is known as the Great Cipher because it remained unsolved from its initial use until 1890, when French military cryptanalyst, Étienne Bazeries solved it.

[27] An encrypted message from the time of the Man in the Iron Mask (decrypted just prior to 1900 by Étienne Bazeries) has shed some, regrettably non-definitive, light on the identity of that real, if legendary and unfortunate, prisoner.

Although cryptography has a long and complex history, it wasn't until the 19th century that it developed anything more than ad hoc approaches to either encryption or cryptanalysis (the science of finding weaknesses in crypto systems).

Examples of the latter include Charles Babbage's Crimean War era work on mathematical cryptanalysis of polyalphabetic ciphers, redeveloped and published somewhat later by the Prussian Friedrich Kasiski.

Understanding of cryptography at this time typically consisted of hard-won rules of thumb; see, for example, Auguste Kerckhoffs' cryptographic writings in the latter 19th century.

In particular he placed a notice of his abilities in the Philadelphia paper Alexander's Weekly (Express) Messenger, inviting submissions of ciphers, most of which he proceeded to solve.

[28] He later wrote an essay on methods of cryptography which proved useful as an introduction for novice British cryptanalysts attempting to break German codes and ciphers during World War I, and a famous story, The Gold-Bug, in which cryptanalysis was a prominent element.

However, its most important contribution was probably in decrypting the Zimmermann Telegram, a cable from the German Foreign Office sent via Washington to its ambassador Heinrich von Eckardt in Mexico which played a major part in bringing the United States into the war.

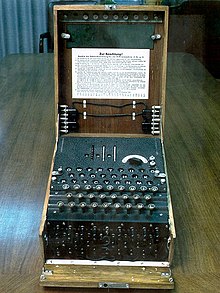

Mathematical methods proliferated in the period prior to World War II (notably in William F. Friedman's application of statistical techniques to cryptanalysis and cipher development and in Marian Rejewski's initial break into the German Army's version of the Enigma system in 1932).

[30] Rejewski and his mathematical Cipher Bureau colleagues, Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski, continued reading Enigma and keeping pace with the evolution of the German Army machine's components and encipherment procedures for some time.

As the Poles' resources became strained by the changes being introduced by the Germans, and as war loomed, the Cipher Bureau, on the Polish General Staff's instructions, on 25 July 1939, at Warsaw, initiated French and British intelligence representatives into the secrets of Enigma decryption.

In due course, the British cryptographers – whose ranks included many chess masters and mathematics dons such as Gordon Welchman, Max Newman, and Alan Turing (the conceptual founder of modern computing) – made substantial breakthroughs in the scale and technology of Enigma decryption.

At the end of the War, on 19 April 1945, Britain's highest level civilian and military officials were told that they could never reveal that the German Enigma cipher had been broken because it would give the defeated enemy the chance to say they "were not well and fairly beaten".

Bletchley Park called them the Fish ciphers; Max Newman and colleagues designed and deployed the Heath Robinson, and then the world's first programmable digital electronic computer, the Colossus, to help with their cryptanalysis.

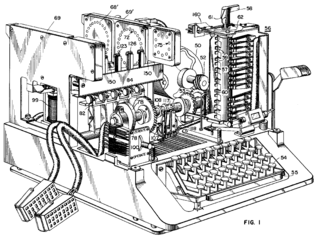

A US Army group, the SIS, managed to break the highest security Japanese diplomatic cipher system (an electromechanical stepping switch machine called Purple by the Americans) in 1940, before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Allied cipher machines used in World War II included the British TypeX and the American SIGABA; both were electromechanical rotor designs similar in spirit to the Enigma, albeit with major improvements.

Even after encryption systems were broken, large amounts of work were needed to respond to changes made, recover daily key settings for multiple networks, and intercept, process, translate, prioritize and analyze the huge volume of enemy messages generated in a global conflict.

Shannon wrote a further article entitled "A mathematical theory of communication" which highlights one of the most significant aspects of his work: cryptography's transition from art to science.

In proving "perfect secrecy", Shannon determined that this could only be obtained with a secret key whose length given in binary digits was greater than or equal to the number of bits contained in the information being encrypted.

The proposed DES cipher was submitted by a research group at IBM, at the invitation of the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST), in an effort to develop secure electronic communication facilities for businesses such as banks and other large financial organizations.

After advice and modification by the NSA, acting behind the scenes, it was adopted and published as a Federal Information Processing Standard Publication in 1977 (currently at FIPS 46-3).

[citation needed] Various classified papers were written at GCHQ during the 1960s and 1970s which eventually led to schemes essentially identical to RSA encryption and to Diffie–Hellman key exchange in 1973 and 1974.

[40] The public developments of the 1970s broke the near monopoly on high quality cryptography held by government organizations (see S Levy's Crypto for a journalistic account of some of the policy controversy of the time in the US).

He distributed a freeware version of PGP when he felt threatened by legislation then under consideration by the US Government that would require backdoors to be included in all cryptographic products developed within the US.

Notable examples of broken crypto designs include the first Wi-Fi encryption scheme WEP, the Content Scrambling System used for encrypting and controlling DVD use, the A5/1 and A5/2 ciphers used in GSM cell phones, and the CRYPTO1 cipher used in the widely deployed MIFARE Classic smart cards from NXP Semiconductors, a spun off division of Philips Electronics.

Quantum computers, if ever constructed with enough capacity, could break existing public key algorithms and efforts are underway to develop and standardize post-quantum cryptography.