History of electric power transmission

London's system delivered 7,000 horsepower (5.2 MW) over a 180-mile (290 km) network of pipes carrying water at 800 pounds per square inch (5.5 MPa).

[5][6][7] Yablochkov candles required high voltage, and it was not long before experimenters reported that the arc lamps could be powered on a 14-kilometre (8.7 mi) circuit.

This San Francisco system was the first case of a utility selling electricity from a central plant to multiple customers via transmission lines.

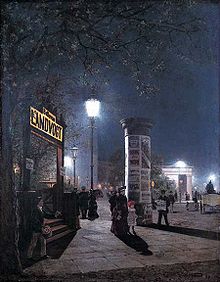

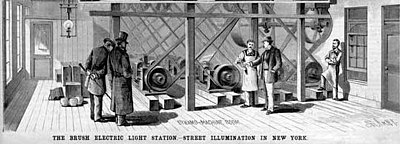

In December 1880, Brush Electric Company set up a central station to supply a 2-mile (3.2 km) length of Broadway with arc lighting.

By the end of 1881, New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Montreal, Buffalo, San Francisco, Cleveland and other cities had Brush arc lamp systems, producing public light well into the 20th century.

[18] After devising a commercially viable incandescent light bulb in 1879, Edison went on to develop the first large scale investor-owned electric illumination "utility" in lower Manhattan, eventually serving one square mile with 6 "jumbo dynamos" housed at Pearl Street Station.

[22] Prior to efficient turbogenerators, hydroelectric projects were a significant source of large amounts of power requiring transmission infrastructure.

When George Westinghouse became interested in electricity, he quickly and correctly concluded that Edison's low voltages were too inefficient to be scaled up for transmission needed for large systems.

He further understood that long-distance transmission needed high voltage and that inexpensive conversion technology only existed for alternating current.

[23] In 1876, Pavel Yablochkov patented his mechanism of using induction coils to serve as a step up transformer prior to the Paris Exposition demonstrating his arc lamps.

In 1881, Lucien Gaulard and John Dixon Gibbs developed a more efficient device which they dubbed the secondary generator, namely an early step down transformer whose ratio could be adjusted by configuring the connections between a series of wired bobbins around a spindle, from which an iron core could be added or removed as necessary to vary the power output.

It was powered by a 2-kV, 130-Hz Siemens & Halske alternator and featured several Gaulard secondary generators with their primary windings connected in series, which fed incandescent lamps.

In both designs, the magnetic flux linking the primary and secondary windings travels almost entirely within the iron core, with no intentional path through air.

These revolutionary design elements would finally make it technically and economically feasible to provide electric power for lighting in homes, businesses and public spaces.

It was powered by two Siemens & Halske alternators rated 30 hp (22 kW), 2 kV at 120 Hz and used 200 series-connected Gaulard 2-kV/20-V step-down transformers provided with a closed magnetic circuit, one for each lamp.

The modern 3-phase system was developed by Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky and Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft and Charles Eugene Lancelot Brown in Europe, starting in 1889.

The exhibition featured the first long-distance transmission of high-power, three-phase electric current, which was generated 175 km away at Lauffen am Neckar.

As a result of the successful field trial, three-phase current, as far as Germany was concerned, became the most economical means of transmitting electrical energy.

Rene Thury, who had spent six months at Edison's Menlo Park facility, understood his problem with transmission and was convinced that moving electricity over great distances was possible using direct current.

[37][38][42] Ultimately, the versatility of the Thury system was hampered by the fragility of series distribution, and the lack of a reliable DC conversion technology that would not show up until the 1940s with improvements in mercury arc valves.

Rotary converters and later mercury-arc valves and other rectifier equipment allowed DC load to be served by local conversion where needed.

By using common generating plants for every type of load, important economies of scale were achieved, lower overall capital investment was required, load factor on each plant was increased allowing for higher efficiency, allowing for a lower cost of energy to the consumer and increased overall use of electric power.

Reliability was improved and capital investment cost was reduced, since stand-by generating capacity could be shared over many more customers and a wider geographic area.

Westinghouse also had to develop a system based on rotary converters to allow them to supply all the needed power standards including single phase and polyphase AC and DC for street cars and factory motors.

Westinghouse's initial customer for the power from the hydroelectric generators at the Edward Dean Adams Station at Niagara in 1895 were the plants of the Pittsburgh Reduction Company which needed large quantities of cheap electricity for smelting aluminum.

[50] The first "high voltage" AC power station, rated 4-MW 10-kV 85-Hz, was put into service in 1889 by Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti at Deptford, London.

On April 17, 1929 the first 220 kV line in Germany was completed, running from Brauweiler near Cologne, over Kelsterbach near Frankfurt, Rheinau near Mannheim, Ludwigsburg–Hoheneck near Austria.

De Ferranti in the United Kingdom were instrumental in overcoming technical, economic, regulatory and political difficulties in development of long-distance electric power transmission.

By introduction of electric power transmission networks, in the city of London the cost of a kilowatt-hour was reduced to one-third in a ten-year period.

Uno Lamm developed a mercury valve with grading electrodes making them suitable for high voltage direct current power transmission.