History of gravitational theory

This work was furthered through the Middle Ages by Indian, Islamic, and European scientists, before gaining great strides during the Renaissance and Scientific Revolution—culminating in the formulation of Newton's law of gravity.

In the 14th century, European philosophers Jean Buridan and Albert of Saxony—who were influenced by Islamic scholars such as Ibn Sina and Abu'l-Barakat respectively[1][2]—developed the theory of impetus and linked it to the acceleration and mass of objects.

The pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Heraclitus (c. 535 – c. 475 BC) of the Ionian School used the word logos ('word') to describe a kind of law which keeps the cosmos in harmony, moving all objects, including the stars, winds, and waves.

[9][11] Greek philosopher Strato of Lampsacus (c. 335 – c. 269 BC) rejected the Aristotelian belief of "natural places" in exchange for a mechanical view in which objects do not gain weight as they fall, instead arguing that the greater impact was due to an increase in speed.

[25][26] Greek astronomer Hipparchus of Nicaea (c. 190 – c. 120 BC) also rejected Aristotelian physics and followed Strato in adopting some form of theory of impetus to explain motion.

It is manifest from this that ... people situated at distances of a fourth part of the circumference [of earth] from us or in the opposite hemisphere, cannot by any means fall downwards [in space].

[46] In the 11th century, Persian polymath Ibn Sina (Avicenna) agreed with Philoponus' theory that "the moved object acquires an inclination from the mover" as an explanation for projectile motion.

Unlike Philoponus, who believed that it was a temporary virtue that would decline even in a vacuum, Ibn Sina viewed it as a persistent, requiring external forces such as air resistance to dissipate it.

[2] According to Shlomo Pines, al-Baghdādī's theory of motion was "the oldest negation of Aristotle's fundamental dynamic law [namely, that a constant force produces a uniform motion], [and is thus an] anticipation in a vague fashion of the fundamental law of classical mechanics [namely, that a force applied continuously produces acceleration].

[55][b] They attributed the motion of objects to an impetus (akin to momentum), which varies according to velocity and mass;[55] Buridan was influenced in this by Ibn Sina's Book of Healing.

[1] Buridan and the philosopher Albert of Saxony (c. 1320 – c. 1390) adopted Abu'l-Barakat's theory that the acceleration of a falling body is a result of its increasing impetus.

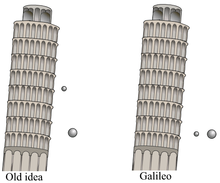

But because this comes about by reason of the position of heavy bodies, let it be called a positional gravity [i.e. gravitas secundum situm][67]By 1544, according to Benedetto Varchi, the experiments of at least two Italians, Francesco Beato, a Dominican philosopher at Pisa, and Luca Ghini, a physician and botanist from Bologna, had dispelled the Aristotelian claim that objects fall at speeds proportional to their weight.

[69] This idea was subsequently explored in more detail by Galileo Galilei, who derived his kinematics from the 14th-century Merton College and Jean Buridan,[55] and possibly De Soto as well.

[69] In 1585, Flemish polymath Simon Stevin performed a demonstration for Jan Cornets de Groot, a local politician in the Dutch city of Delft.

[71][72] Let us take (as ... Jan Cornets de Groot ... and I have done) two balls of lead, the one ten times larger and heavier than the other, and drop them together from a height of 30 feet on to a board or something on which they give a perceptible sound.

[80][h] I have arrived at a proposition, ... namely, that spaces traversed in natural motion are in the squared proportion of the times.Written with modern symbols: s ∝ t2 The result was published in Two New Sciences in 1638.

If two stones were set near one another in some place in the world outside the sphere of influence of a third kindred body, these stones, like two magnetic bodies, would come together in an intermediate place, each approaching the other by a space proportional to the bulk [moles] of the other....[83]A disciple of Galileo, Evangelista Torricelli reiterated Aristotle's model involving a gravitational centre, adding his view that a system can only be in equilibrium when the common centre itself is unable to fall.

[66] The relation of the distance of objects in free fall to the square of the time taken was confirmed by Francesco Maria Grimaldi and Giovanni Battista Riccioli between 1640 and 1650.

Thus, centrifugal force thrusts relatively light matter away from the central vortices of celestial bodies, lowering density locally and thereby creating centripetal pressure.

[88][i] Nicolas Fatio de Duillier (1690) and Georges-Louis Le Sage (1748) proposed a corpuscular model using some sort of screening or shadowing mechanism.

In 1784, Le Sage posited that gravity could be a result of the collision of atoms, and in the early 19th century, he expanded Daniel Bernoulli's theory of corpuscular pressure to the universe as a whole.

English mathematician Isaac Newton used Descartes' argument that curvilinear motion constrains inertia,[90] and in 1675, argued that aether streams attract all bodies to one another.

[j] Newton (1717) and Leonhard Euler (1760) proposed a model in which the aether loses density near mass, leading to a net force acting on bodies.

[96] In 1687, with Halley's support (and to Hooke's dismay), Newton published Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), which hypothesizes the inverse-square law of universal gravitation.

In 1755, Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant published a cosmological manuscript based on Newtonian principles, in which he develops an early version of the nebular hypothesis.

[106] Newton's theory enjoyed its greatest success when it was used to predict the existence of Neptune based on motions of Uranus that could not be accounted by the actions of the other planets.

[113] In 1922, Jacobus Kapteyn proposed the existence of dark matter, an unseen force that moves stars in galaxies at higher velocities than gravity alone accounts for.

Based on the principle of relativity, Henri Poincaré (1905, 1906), Hermann Minkowski (1908), and Arnold Sommerfeld (1910) tried to modify Newton's theory and to establish a Lorentz invariant gravitational law, in which the speed of gravity is that of light.

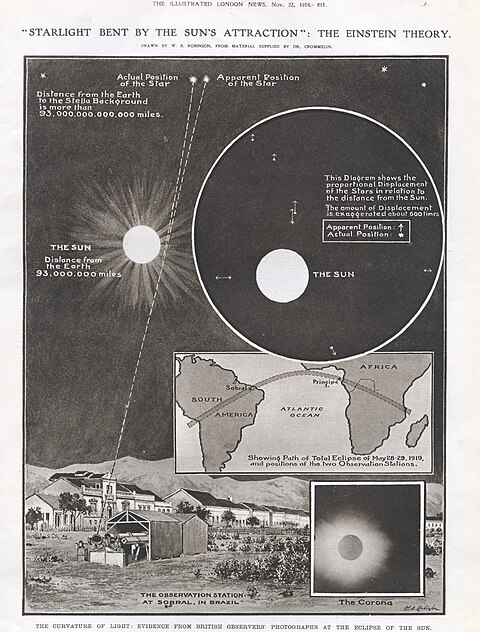

Notable solutions of the Einstein field equations include: General relativity has enjoyed much success because its predictions (not called for by older theories of gravity) have been regularly confirmed.

[126][127] This reproduces general relativity in the classical limit, but only at the linearized level and postulating that the conditions for the applicability of Ehrenfest theorem holds, which is not always the case.