History of herbalism

Evidence-based use of pharmaceutical drugs, often derived from medicinal plants, has largely replaced herbal treatments in modern health care.

For instance, a 60,000-year-old Neanderthal burial site, "Shanidar IV", in northern Iraq has yielded large amounts of pollen from 8 plant species, 7 of which are used now as herbal remedies.

[7] In Mesopotamia, the written study of herbs dates back over 5,000 years to the Sumerians, who created clay tablets with lists of hundreds of medicinal plants (such as myrrh and opium).

[9] While physical documents are scarce, texts such as the Papyrus Ebers serve to illuminate and relieve some of the conjecture surrounding ancient herbal practices.

The recipes and remedies included in parts of the Corpus no doubt reveal popular and prevalent treatments of the early ancient Greek period.

Though any of the herbals included in the Corpus are similar to those practiced in the religious sectors of healing, they differ strikingly in the lack of rites, prayers, or chants used in the application of remedies.

[18] Galen of Pergamon, a Greek physician practicing in Rome, was certainly prolific in his attempt to write down his knowledge on all things medical—and in his pursuit, he wrote many texts regarding herbs and their properties, most notably his Works of Therapeutics.

[19] While the subject of therapeutics encompasses a wide array of topics, Galen's extensive work in the humors and four basic qualities helped pharmacists to better calibrate their remedies for the individual person and their unique symptoms.

[21] Though the original texts no longer exist, many medical scholars throughout the ages have quoted Diocles rather extensively, and it is in these fragments that we gain knowledge of his writings.

[22] It is purported that Diocles actually wrote the first comprehensive herbal- this work then cited numerous times by contemporaries such as Galen, Celsus, and Soranus.

With over 900 drugs and plants listed, Pliny's writings provide a very large knowledge base upon which we may learn more about ancient herbalism and medical practices.

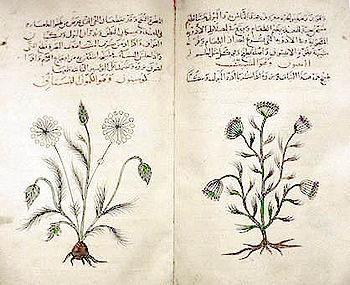

[24] Much like Pliny, Pedanius Dioscorides constructed a pharmacopeia, De Materia Medica, consisting of over 1000 medicines produced form herbs, minerals, and animals.

[29] The first point of view dictates that the information presented in these medieval texts were merely copied from their classical equivalents without much thought or understanding.

[29] The second viewpoint, which is gaining traction among modern scholars, states that herbals were copied for actual use and backed by genuine understanding.

Dioscorides was a Greek physician and botanist in 50 AD who devoted his life's work to understanding plants and the use of their properties in medicine.

The most essential herbs that were used in the Middle Ages are elderberry, wild sage, rosehips, plantain, calendula, comfrey, yarrow, nettle, and many more.

However, most of these monastic scholars' efforts were focused on translating and copying ancient Greco-Roman and Arabic works, rather than creating substantial new information and practices.

The monasteries thus tended to become local centers of medical knowledge, and their herb gardens provided the raw materials for simple treatment of common disorders.One of the most famous women in the herbal tradition was Hildegard of Bingen.

[35][better source needed] At the same time, folk medicine in the home and village continued uninterrupted, supporting numerous wandering and settled herbalists.

A great scholar of the Arabian School was Avicenna, who wrote The Canon of Medicine which became the standard medical reference work of the Arab world.

A common misconception is that one can know early medieval medicine simply by identifying texts, but it is difficult to compose a clear understanding of herbals without prior knowledge.

Gerard's text was basically a pirated translation of a book by the Belgian herbalist Dodoens and his illustrations came from a German botanical work.

Culpeper's blend of traditional medicine with astrology, magic, and folklore was ridiculed by the physicians of his day, yet his book—like Gerard's and other herbals—enjoyed phenomenal popularity.

A century later, Paracelsus introduced the use of active chemical drugs (like arsenic, copper sulfate, iron, mercury, and sulfur).

John Bartram was a botanist that studied the remedies that Native Americans would share and often included bits of knowledge of these plants in printed almanacs.

They distinguished themselves from "regular" doctors of the time who used calomel and bloodletting, and led to a brief renewal of the empirical method in herbal medicine.

Disease was a matter of maladjustment in the body's internal heat, and could be cured by applying certain herbs and medicinal plants, coupled with vomiting, enemas, and steam baths.

Many herbs he popularized, such as cayenne pepper, lobelia, and goldenseal, remain widely used to this day in herbal healing routines.

In China, Mao Zedong reintroduced traditional Chinese medicine, which relied heavily on herbalism, into the health care system in 1949.

"[54] Many alternative physicians in the 21st century incorporate herbalism in traditional medicine due to the diverse abilities plants have and their low number of side effects.