History of alternative medicine

But homeopathy, with its remedies made of water, was harmless compared to the unscientific and dangerous orthodox western medicine practiced at that time, which included use of toxins and draining of blood, often resulting in permanent disfigurement or death.

[1] Other alternative practices such as chiropractic and osteopathy, were developed in the United States at a time that western medicine was beginning to incorporate scientific methods and theories, but the biomedical model was not yet fully established.

[19] Although more neutral than either pejorative or promotional designations such as "quackery" or "natural medicine", cognate terms like "unconventional", "heterodox", "unofficial", "irregular", "folk", "popular", "marginal", "complementary", "integrative" or "unorthodox" define their object against the standard of conventional biomedicine,[20] entail particular perspectives and judgements, often carry moral overtones, and can be inaccurate.

[21] The shifting nature of these terms is underlined by recent efforts to demarcate between alternative treatments on the basis of efficacy and safety and to amalgamate those therapies with scientifically adjudged value into complementary medicine as a pluralistic adjunct to conventional practice.

[26] Among regular practitioners, university trained physicians formed a medical elite while provincial surgeons and apothecaries, who learnt their art through apprenticeship, made up the lesser ranks.

[28] The theories and practices included the science of anatomy and that the blood circulated by a pumping heart, and contained some empirically gained information on progression of disease and about surgery, but were otherwise unscientific, and were almost entirely ineffective and dangerous.

[39] France provides perhaps one of the earliest examples of the emergence of a state-sanctioned medical orthodoxy – and hence also of the conditions for the development of forms of alternative medicine – the beginnings of which can be traced to the late eighteenth century.

[41] This system was radically transformed during the early phases of the French Revolution when both the traditional faculties and the new institutions under royal sponsorship were removed and an entirely unregulated medical market was created.

[58] It also reflected Mesmer's doctoral thesis, De Planatarum Influxu ("On the Influence of the Planets"), which had investigated the impact of the gravitational effect of planetary movements on fluid-filled bodily tissues.

[60] The immediate impetus for his medical speculation, however, derived from his treatment of a patient, Franzisca Oesterlin, who suffered from episodic seizures and convulsions which induced vomiting, fainting, temporary blindness and paralysis.

[62] By 1775 Mesmer's Austrian practice was prospering and he published the text Schrieben über die Magnetkur an einen auswärtigen Arzt which first outlined his thesis of animal magnetism.

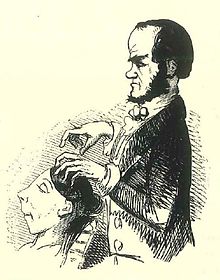

[66] Mesmer, through the apparent force of his will – not infrequently assisted by an intense gaze or the administration of his wand – would then direct these energies into the afflicted bodies of his patients seeking to provoke either a "crisis" or a trance-like state; outcomes which he believed essential for healing to occur.

[67] Popular caricature of mesmerism emphasised the eroticised nature of the treatment as spectacle: "Here the physician in a coat of lilac or purple, on which the most brilliant flowers have been painted in needlework, speaks most consolingly to his patients: his arms softly enfolding her sustain her in her spasms, and his tender burning eye expresses his desire to comfort her".

[68] Responding chiefly to the hint of sexual impropriety and political radicalism imbuing these séances, in 1784 mesmerism was subject to a commission of inquiry by a royal-appointed scientific panel of the prestigious French Académie de Médicine.

[76] Initially supported by The Lancet, a reformist medical journal,[77] he contrived to demonstrate the scientific properties of animal magnetism as a physiological process on the predominantly female charity patients under his care in the University College Hospital.

[78] He sought to reduce his subjects to the status of mechanical automata claiming that he could, through the properties of animal magnetism and the pacifying altered states of consciousness which it induced, "play" their brains as if they were musical instruments.

[80] When in states of mesmeric entrancement the O'Key sisters, due to the apparent increased sensitization of their nervous system and sensory apparatus, behaved as if they had the ability to see through solid objects, including the human body, and thus aid in medical diagnosis.

As their fame rivalled that of Elliotson, however, the O'Keys behaved less like human diagnostic machines and became increasingly intransigent to medical authority and appropriated to themselves the power to examine, diagnose, prescribe treatment and provide a prognosis.

[83] Perturbed by the O'Key's provocative displays, Wakely convinced Elliotson to submit his mesmeric practice to a trial in August 1838 before a jury of ten gentlemen during which he accused the sisters of fraud and his colleague of gullibility.

[91] These mesmeric theatres, intended in part as a means of soliciting profitable private clientele, functioned as public fora for debate between skeptics and believers as to whether the performances were genuine or constituted fraud.

[91] In order to establish that the loss of sensation under mesmeric trance was real, these itinerant mesmerists indulged in often quite violent methods – including discharging firearms close to the ears of mesmerised subjects, pricking them with needles, putting acid on their skin and knives beneath their fingernails.

[97] This marked the beginning of a campaign by London mesmerists to gain a foothold for the practice within British hospitals by convincing both doctors and the general public of the value of surgical mesmerism.

[101] By the 1830s mesmerism was making headway in the United States amongst figures like the intellectual progenitor of the New Thought movement, Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, whose treatment combined verbal suggestion with touch.

[103] In the 1840s the American spiritualist Andrew Jackson Davis sought to combine animal magnetism with spiritual beliefs and postulated that bodily health was dependent upon the unobstructed movement of the "spirit", conceived as a fluid substance, throughout the body.

[119] Ayurveda can be defined as the system of medicine described in the great medical encyclopedias associated with the names Caraka, Suśruta, and Bhela, compiled and re-edited over several centuries from about 200 BCE to about 500 CE and written in Sanskrit.

[citation needed] Ayurveda originally derived from the Vedas, as the name suggests, and was first organized and captured in Sanskrit in ciphered form by physicians teaching their students judicious practice of healing.

Harkin criticized the "unbendable rules of randomized clinical trials" and, citing his use of bee pollen to treat his allergies, stated: "It is not necessary for the scientific community to understand the process before the American public can benefit from these therapies.

[137] The terms 'alternative' and 'complementary' tend to be used interchangeably to describe a wide diversity of therapies that attempt to use the self-healing powers of the body by amplifying natural recuperative processes to restore health.

[141] The natural law of similia similibus curantur, or 'like is cured by like', was recognised by Hippocrates but was only developed as a practical healing system in the early 19th century by a German, Dr Samuel Hahnemann.

Originating in Japan, cryotherapy has been developed by Polish researchers into a system that claims to produce lasting relief from a variety of conditions such as rheumatism, psoriasis and muscle pain.